Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790–1840 by Michael J. Hatch

Reviewed by Patricia J. YuPatricia J. Yu

Kenyon College

Email the author: yu6[at]kenyon.edu

Citation: Patricia J. Yu, book review of Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790–1840 by Michael J. Hatch, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.16.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Michael J. Hatch,

Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790–1840.

University Park: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024.

222 pp.; 20 color and 42 b&w illus.; glossary of names and foreign terms; notes; bibliography; index.

$119.95 (hardcover)

$95.99 (ebook)

ISBN: 9780271095578

In 1803, the scholar-official Ruan Yuan (1764–1849) commissioned a handscroll painting depicting him seated on a rootwood chair in his Accumulated Antiquities Studio, surrounded by ancient bronze vessels, inscribed bricks, and inkstones from his collection (fig. 1). Seated across from Ruan, his companion does not simply look at a rectangular bronze ding (tripod vessel) but picks it up and caresses its surface. The sensory aspect of touch—of direct bodily contact—is further emphasized by the clear image of a handprint impressed into the ancient brick on the table in front of Ruan’s companion. Sharing the same table space is an open book, its pages blank as if ready to catalogue the collection. Object. Touch. Record. But what form does a record take? It is not enough to provide a descriptive summary or even a transcription of the texts cast in bronze or carved in stone. The painting itself offers a kind of record—a record of a moment, the sitters, and the collection; but the painting alone is an insufficient record: appended to the painting are rubbings of each antique inscription on the object bodies that offered a one-to-one indexical record of scale, condition, and direct apprehension.

As the cover image, this painting gestures toward the central concerns of Michael J. Hatch’s Networks of Touch: A Tactile History of Chinese Art, 1790–1840. The first full-length study of elite art in early nineteenth-century China, Networks of Touch covers a period caught between the height of the Qianlong emperor’s reign and the cataclysms of the Opium Wars. Recent exhibitions have drawn greater attention to nineteenth-century China: China’s 8 Brokens: Puzzles of the Treasured Past at the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, in 2017 offered a close look at the visualization of fragmented antiques as a confrontation with modernity; and China’s Hidden Century, 1796–1912 at the British Museum in 2023 offered a broad overview of the entire period.[1] Hatch’s study, which is structured around Ruan’s social and professional network, offers a tighter scope that complements both. Through their engagement with inscriptions preserved on the surfaces of ancient objects, these men—and there are only men in this study—developed and promoted an “epigraphic aesthetic” in elite visual and material culture that forged connections among varied objects—rubbings, calligraphy, paintings, seals, and teapots. The creation and circulation of these works further depended on, created, and reinforced the social networks of “tactful literati” who shared an interest in “tactile thinking,” by which “to touch was to understand” the distant past (5). The book is the latest addition to the Perspectives on Sensory History series published by Penn State University Press.

How do we know the past? How can we confirm the accuracy and validity of historic texts that have been transmitted through handwritten copies when the very material reality of these documents (e.g., ink, paper, silk, and even the human fallibility in transcription) leads to ephemerality, loss, and erasure? For literati scholars in mid-eighteenth-century China, the potential for muddled transmission instigated a turn towards kaozheng xue (evidential scholarship), which prioritized epigraphic evidence preserved on ancient bronzes and stone steles as a means for capturing authentic texts and authoritative voices from the past.

Chapter 1, “Calligraphy’s New Past,” introduces Ruan’s engagement with evidential scholarship by tracing the geographic contours of his career as a civil servant. Stationed in Shandong during his early career as education commissioner, Ruan was welcomed into the network of noted antiquarian Huang Yi (1744–1802), where Ruan’s access to the Confucian steles at Qufu resulted in his cataloging of those steles in Epigraphy Gazetteer for Shandong Province (1796). When he was later transferred to Zhejiang province in the South, he moved from the geographic source of epigraphy to the center of artistic production in Hangzhou. His full engagement with the epigraphic aesthetic across mediums is treated in the following chapters; here, Hatch establishes that Ruan and his network were “friends in stone,” a phrase that alluded to an enduring friendship, but also the shared passion for ancient steles. These friendships in stone were made literal in the exchange of paintings, calligraphy, seals, and inkstones. These objects not only made possible the very act of writing that united these men but also carried on their bodies the inscribed form of each man’s calligraphy, which was in turn stylistically adapted from the form of ancient calligraphy as preserved on the steles that they loved. This chapter concludes with two of Ruan’s most influential essays, Nan bei shu pai lun (“Southern and Northern Schools of Calligraphy”) and Bei bei nan tie lun (“Northern Steles and Southern Letters”), which were drafted around 1810 and published together in 1823. In these texts, Ruan proposed a new lineage for calligraphy: one that was anchored in the clerical style—“squared, strict, and disciplined”—as seen in stele inscriptions (fig. 2). The perceived “antique and awkward” style of clerical script was associated with moral uprightness and candor in contrast to the “clever and appealing” sinuous lines of running script that showed off the gestural genius of the canonical masters (39). Most importantly, the provenance of clerical script was undisputed; preserved on the surface of stone, it offered direct contact with the ancient past.

Chapters 2 and 3, and some of chapter 4, are adapted from Hatch’s earlier articles.[2] Chapter 2, “Obliterated Texts,” focuses on Ruan’s antiquarian colleague, Huang Yi, and Huang’s publication Xiao Penglai ge jinshi wenzi (Engraved Texts of the Lesser Penglai Pavilion, 1800). Huang’s travels in search of ancient stele inscriptions and his rediscovery of the Wu Family Shrines has been addressed in previous scholarship.[3] Hatch expands on studies of Huang’s antiquarianism by turning his attention towards Huang’s reproduction of his rubbing collection in Engraved Texts, particularly Huang’s notable decision to reproduce the rubbings in the “outline method” (also known as the “double hook method”; fig. 3). In this reproductive mode, the characters’ contours are traced. Rather than enhancing textual legibility and reproducing a calligraphic gesture carved into stone, it is the very material degradation of a worn stone surface that is reproduced and emphasized.

Chapter 3, “Epigraphic Painting,” opens with the adoption of the “antique and awkward” epigraphic aesthetic by artists like Jin Nong and Luo Ping. The primary case study in chapter 3 is a monochrome ink handscroll painting, Presenting the Tripod at Mt. Jiao (1803) that documents the actual event where Ruan donated an inscribed Western Zhou bronze tripod—the so-called Taoling tripod—to the Dinghui Temple. Hatch presents the handscroll’s full object biography—the bronze vessel itself, the event of its gifting, the painting commemorating the event, and the attached colophons created in response to it (fig. 4). The colophon from 1860 situates the commemorative painting by Wang Xuehao within a genealogy of “brush intentions” of past painters; in contrast, a slightly earlier response from 1845 involved remounting Wang’s painting with the rubbings of the Taoling bronze’s inscription. The case study encapsulates how elite literati culture in the early nineteenth century remained fluent in the brushwork of earlier painting masters, but also prioritized the indexical authority of a rubbing that elided the brushwork paradigm altogether.

In chapter 4, “Tactile Images,” Hatch examines the contributions of the “epigrapher-monk” Liuzhou (1791–1858) to the further development of rubbing techniques. Earlier rubbings were largely two-dimensional in their focus on inscriptions; “full-form,” also known as composite rubbings, combined surface rubbings with in-painting and printing to replicate the three-dimensional form of a vessel on a two-dimensional plane. Liuzhou furthered the full-form technique by doubling the object in the picture plane to present it fully in the round (fig. 5). Liuzhou often collaborated with his artist friends to create some of the most delightful works of this period in which his composite rubbings of antiques are coupled with his own miniature painted portrait depicted in direct physical contact with the object itself (fig. 6). The chapter concludes by connecting Liuzhou’s Buddhist faith with his epigraphic practice.

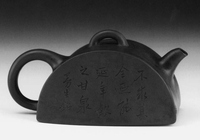

The central figure of chapter 5, “A Tactful Literatus,” is Chen Hongshou (1768–1822), who was embedded within the network of scholar-artists in Hangzhou and who later served as a long-time aide to Ruan. Adept in many mediums, Chen carved seals with the “iron brush” of a chisel, painted with his fingers, and collaborated with ceramic artists in making and inscribing teapots (fig. 7). By moving through the multiple mediums of Chen’s artistic production, Hatch argues that Chen exemplified the “tactile thinking” that engaged with the deep layers of past allusions, while simultaneously bypassing the brush and resisting the “fetishization of brushwork” (131, 145).

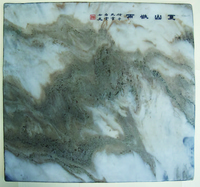

The last chapter, “The Limits of Touch,” returns to Ruan at the end of his career, when he was stationed as the governor of Yunnan and Guizhou. Just as his earlier geographic locales informed his epigraphic scholarship, here in southwest China, Ruan encountered the striated Dali marble that appeared to replicate the effects of monochrome ink landscape painting in its polished mineral surface (fig. 8). Ruan collected these striking stones, inscribed them, and sent them to his friends. In characteristic fashion, he made a record of each stone and inscription, resulting in the five-volume publication Shi hua ji (Paintings in Stone). In his close reading of Ruan’s text, Hatch notes that while Ruan identifies the correspondences between the “touchless” natural effects of the stone and the styles of canonical brushwork, he does so to underscore the primacy of “heaven’s patterns” and to promote a return to “direct and unmediated contact with the world” (156). Hatch concludes the chapter by returning to inscribed teapots and the ways in which the social acts of collaborative making, poetic allusions, visual and textual punning, and the literal actions of tea brewing and drinking reinforced the ties among the “tactful literati” who shared intellectual and sensory experiences (159).

Networks of Touch deftly offers a corrective to the dismissal of literati art of the early nineteenth century as merely a hidebound continuation of early Qing painting orthodoxy; rather, Hatch convincingly argues that early nineteenth-century artists, in their questioning of brushwork lineages and their turn towards the deeper excavated past, were engaging in a studied “antagonism to the canon” that situates them in continuity with the later challenges mounted by the artists in mid- and late-nineteenth-century Shanghai in the aftermath of the Opium Wars (164). Hatch nimbly moves among the lives of these literati men, the ancient objects they collected, the modes of recording and reproducing those objects in text and rubbing, and the epigraphic aesthetic that blossoms from the direct contact with the past. This book is suitable for specialists, graduate students, and advanced undergraduates who are interested in antiquarian studies, literati culture, art and sociality, the interplay of text and image, translation across mediums, and modes of reproduction.

On a final note, it should be mentioned that the high cost of the hardcover book is unfortunately not reflected in the quality of the printing. Although serviceable and legible, the printed text and images exhibit just the slightest touch of blurriness that might be distracting for sharp-eyed readers. Considering that much of the author’s argument is based on both the form and content of inscriptions, one is left wishing that many of the included illustrations were larger, sharper, and presented with better contrast. Some readers may, therefore, prefer the digital version, where the text remains sharp, and images can be enlarged. This criticism is indeed the most minor of quibbles and in no way detracts from Hatch’s contribution to the field of early nineteenth-century Chinese art. For this reviewer at least, the physical book is a tactile reminder of the visual and material translations between a digital manuscript and its tangible form as printed ink on paper. Perhaps it is only appropriate that, in the end, the hardcover version of Networks of Touch offers a metacommentary on its own material existence that resonates with the worn surfaces and blurred edges of the ancient stele inscriptions encountered within its pages.

Notes

[1] Nancy Berliner, The 8 Brokens: Chinese Bapo Painting (Boston: MFA Publications, 2018); Jessica Harrison-Hall and Julia Lovell, eds., China’s Hidden Century, 1796–1912 (London: The British Museum, 2023).

[2] Michael J. Hatch, “Outline, Brushwork, and the Epigraphic Aesthetic in Huang Yi’s Engraved Texts of the Lesser Penglai Pavilion (1800),” Archives of Asian Art 70, no. 1 (April 2020): 23–49; Michael J. Hatch, “Epigraphic and Art Historical Responses to Presenting the Tripod, by Wang Xuehao (1803),” Metropolitan Museum Journal 54 (2019): 87–105.

[3] Wu Hung, The Wuliang Shrine: The Ideology of Early Chinese Pictorial Art (Palo Alto, CA: Stanford University Press, 1989); Lillian L. Y. Tseng, “Retrieving the Past, Inventing the Memorable: Huang Yi’s Visit to the Song-Luo Monuments,” in Monuments and Memory, Made and Unmade, eds. Robert S. Nelson and Margaret Olin (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003), 37–58.