William Rimmer: Champion of Imagination in American Art by Dorinda Evans

Reviewed by Sarah BurnsSarah Burns

Indiana University Bloomington

Email the author: burns[at]indiana.edu

Citation: Sarah Burns, book review of William Rimmer: Champion of Imagination in American Art by Dorinda Evans, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.7.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Dorinda Evans,

William Rimmer: Champion of Imagination in American Art.

Cambridge, UK: Open Book Publishers, 2022.

250 pp.; 98 color and 47 b&w illus.; bibliography; notes; index.

£35.95 (hardback)

ISBN: 9781800647572

£25.95 (paperback)

ISBN: 9781800647565

£5.99 (e-book)

ISBN: 9781800647596

Free (PDF)

ISBN: 9781800647589

In this groundbreaking new study, Dorinda Evans’s very first statement maps out the problem, one might say, of painter / sculptor / anatomist / doctor / spiritualist / shoemaker / teacher William Rimmer (1816–79). He was, she contends, “a major and highly influential American artist, who, fairly consistently, managed to be misunderstood” (1). While the term “highly influential” might be subject to debate, there is no question that Rimmer has endlessly puzzled and intrigued the few scholars who have taken on the challenge of interpreting his perplexing pictorial and sculptural output. In that opening assertion, Evans implicitly sets herself up as the one best equipped to rise to the challenge, rectify chronic misunderstandings, and offer new interpretations based largely on her conviction that Rimmer was both a bipolar personality and an authentic visionary whose mental states and flights of mystical fancy became the unshakable foundation of his art.

Anyone having even a nodding acquaintance with the Rimmer literature knows that one of the most indelible stories, or myths, about his origins has played a significant role in our understanding (or misunderstanding) of his complicated psyche. His father, Thomas Rimmer, believed that he was the son of Louis XVI and therefore the rightful heir to the French throne when the Bourbon monarchy was restored in 1815. He further claimed that the slain king’s brother, Louis XVIII, falsely declared Thomas dead and sent secret agents to eliminate him along with any threat he might pose to the pretender’s legitimacy. Evans notes that Thomas was in fact raised in a prosperous English family, but the myth prevailed. For some years, Thomas moved from place to place to evade his imagined pursuers, finally settling in Boston when young William (born in Liverpool) was nine years of age. Purportedly, this troubled and paranoid history played a significant role in shaping William’s life and art.

In the first chapter, “A Secret Inheritance,” Evans interprets Rimmer’s Scene from The Tempest and Scene from Macbeth (both ca. 1850; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit) in light of their pertinence to the themes of disinheritance or usurpation. But her real interest in this chapter is to establish a record of the mental disabilities that plagued the family. Thomas Rimmer experienced manic or hypomanic episodes and labored under the influence of his grandiose delusions. William’s oldest daughter died at the age of forty-one of nervous exhaustion and acute mania, and William himself suffered from what Evans diagnoses as bipolar disorder, which precipitated extreme mood swings ranging from deep depression to maniacal exuberance. This bipolarity, she argues, helps make sense of Rimmer’s voluminous manuscript, “Stephen and Phillip,” in which the titular characters can be interpreted as the warring halves of Rimmer’s own selfhood: one divine, the other demonic, both deeply flawed. Rimmer depicted Phillip as a regal lion; the character of Stephen refers to the martyred saint who had heavenly visions before his death. Like the saint, Evans argues, Rimmer had celestial visionary experiences.

The second chapter, “The Two-Dimensional Portraits in Context,” examines the meager handful of extant works (ten in all) that Rimmer painted for money. No one could argue that these portraits are masterpieces; in fact, they are uneven in quality and states of preservation. They are also, in most ways, quite conventional, despite Evans’s assertions to the contrary. Evans gives a great deal more weight to the “context” than to the portraits, but one of them at least is of interest in suggesting that Rimmer, who studied medicine in a scattershot fashion and worked for a time as a country doctor, would on occasion train a medical eye upon his sitters. Notably, his Portrait of a Young Man (1841; Foxboro Historical Society, Foxboro) exhibits “evidence of an inflammatory arthritis that resulted in a boutonniere deformity of the fingers” (24). This is plausible because that deformity is prominently visible in Rimmer’s painting.

The main thrust of this chapter, however, is to argue that signs of the artist’s bipolarity are embedded in certain portraits as well as several other pieces. Evans contends that “although much remains to be learned about how this illness affects the output of an artist, bipolar painters in a manic state tend to use brighter, warmer, and more contrasting colors; the brushwork is also typically freer. In a depressed state, the artist often paints with darker, colder colors, less contrast, slower motion, and less imagination” (28). Evans offers Rimmer’s portrait of the ancient Revolutionary War veteran Seth Turner (ca. 1841–42; Massachusetts Historical Society, Boston) as evidence. The old man’s face is indeed pallid and even spectral, hovering as it does before a densely dark background. Evans notes that the sitter’s haggard demeanor “conveys deep depression. But this is not necessarily the sitter’s mood. This is the result of the artist’s choices and, because of how it is painted, it could reflect his own state of mind” (30). The important thing to note here is that the portrait could reflect the artist’s state of mind. But does it?

According to Evans, another pictorial clue to Rimmer’s illness is the “inability to gauge correctly the proportions of parts of a figure in relation to the whole” (31). She offers the example of Samson and the Child (ca. 1854; private collection), in which the said child has one leg “noticeably shorter than the other” (31), and of a soapstone Inkstand with Horse Pulling a Stone-Laden Cart (1855–63; Middlebury College Museum of Art, Middlebury), where the horse’s eye sockets and nostrils are misaligned, though those on the left “are more emotionally expressed than on the right” (36). The chapter ends, somewhat incongruously, with two allegorical Civil-War era drawings: Secessia and Columbia (1862; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) in fierce combat, and Dedicated to the 54th Regiment, Massachusetts Volunteers (1863; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which depicts four members of the all-Black 54th Regiment advancing upon the monster of slavery. Evans argues that in not featuring a white leader on horseback (such as in Augustus Saint-Gaudens’s Shaw Memorial), Rimmer’s drawing, which depicts the soldiers in Roman armor, seemingly represents the Abolitionist viewpoint; it rejects any military hierarchy and instead shows the soldiers’ action to be “of the quality of the greatest heroes of antiquity” (44).

Chapter 3, “Self-Expression in Flight and Pursuit,” tackles Rimmer’s best-known and most vexingly mysterious 1872 painting. Set in a palatial, vaguely Middle Eastern interior, the scene features a swarthy man with a craggy profile (signifying a base human type in Rimmer’s typological system) and a dagger in his belt (fig. 1). Obviously in a fever of panic, the man dashes frantically toward a dimly lit aperture up a short flight of steps, while in a parallel hallway, a ghostly shrouded figure bearing a sword gives chase, his pose exactly replicating that of his quarry. On the right loom foreboding shadows, but whoever or whatever casts them remains unseen. A preparatory drawing titled Oh, for the Horns of the Altar (1872 or before; Cushing/Whitney Medical Library, Yale University, New Haven), showing the fugitive alone, reinforces the suggestion that he is in desperate search of the sanctuary supposedly granted by a holy place. Whatever crime he has committed remains a mystery, though the dagger hints at bloodshed. Evans argues persuasively that while Flight and Pursuit has been the subject of multiple interpretations, its “intended meaning is most convincing as an allegory of guilt or of man’s conscience in a state of sin.” Being “an artist with a mystical sensibility,” Rimmer “tended to paint from his innermost thoughts and feelings” and “created mostly for himself” (51).

Evans’s claims are plausible and certainly make more sense than the idea, for example, that the painting alludes to the 1811 massacre of Mameluke warriors by the reigning Turkish Pasha or even (somewhat more believably) that it allegorizes the pursuit and capture of Lincoln assassination co-conspirator John Surrat. Her interpretation is complex, fine-grained, and convoluted, but in essence it rests on Rimmer’s habitual deployment of binaries in his art: conscience and sin, light and dark, human and animal. The fact that Rimmer’s characters, Stephen and Phillip, are aspects of himself lends credence to the theme of the artist’s feelings of culpability for various real or imagined sins as well as the paranoia stemming from the delusions that assailed both Rimmers, father and son. The manuscript even includes references to the shadows that follow evil doers.

Evans identifies a number of Rimmer’s works that likewise establish binaries of one kind or another, including the paired-personification drawings Morning (1869; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) and Evening, or The Fall of Day (fig. 2), the first a song of innocence depicting a beautiful, winged figure holding up a child with a sunflower, the second representing the mighty fallen angel Lucifer about to plunge despairingly into the sea. Rimmer’s sculpture The Dying Centaur (1869; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) plays on the contrast of human (noble) and animal (base), while his Civil War Scene (1860s; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit), which shows a wounded soldier contemplating a miniature portrait as his horse gazes at the carnage beyond, suggests “the contrast of the man’s higher self (love) and lower self (hatred) as exhibited on the battlefield” (68). Evans’s reading of Flight and Pursuit is exhaustive—and, perhaps, exhausting—for the reader. One wonders if she has conclusively settled its meaning once and for all or whether there is still an opening for further interrogation, because even after paying close attention to her carefully argued and well-supported exposition Flight and Pursuit, for me at least, remains a puzzle.

Chapter 4, “Swedenborg and Enigmatic Pictures,” explores Rimmer’s ideal works in the context of his interest in the philosophy of the eighteenth-century scientist and mystic Emanuel Swedenborg (1688–1772), whose theory of correspondences posited the relation of objects in the here and now to the immaterial realm of the spirit and of divine love. In a nutshell, as Evans defines it, Swedenborg “believed in the presence of spirits and angels in everyday life and had visions of visiting heaven and hell in which truths were revealed to him alone so that he was able to provide his own interpretation of the Bible” (82–83). In this chapter, accordingly, Evans applies Swedenborgian interpretations to Rimmer’s more perplexing allegorical paintings, which are loaded with symbolism so arcane that the ordinary viewer, with only a superficial knowledge of Swedenborg, would find utterly inscrutable.

Undaunted, Evans proposes Swedenborgian interpretations of such paintings as the prosaically named and exceedingly murky Horses at a Fountain (1856–57; Art Institute of Chicago), which, she argues, is an allegory of the corruption of the Roman Catholic Church replete with intricate detail comprising reliquaries, a “scabrous, winged devil,” a broken-down cart, a “deluded pilgrim,” and “two growling hound dogs,” along with the titular steeds (85). Evans parses out the painting’s meaning as reflective of Rimmer’s belief that anyone could have a relationship with God without needing Catholic intermediaries. She then proceeds to decode the Swedenborgian symbolism of other allegorical works, proving to be an impressively informed guide. Without Evans’s close interrogation of the Swedenborgian dimensions in Rimmer’s art, I doubt that most of us, if any, would be able to figure out such drawings as Creation (God the Father Creating the Sun and Moon) (1869; Harvard Art Museums/Fogg Museum, Cambridge). She explains that the heavily muscled figure of God is “shockingly naked” because he is a Swedenborgian three-in-one deity: “the unnaturally muscular shoulders and authoritative gestures express power like that of the Father; the naked buttocks and unused legs signal that he is human like the Son; while the flame-like beard suggests tongues of fire like those of the Holy Spirit.” Over God’s head is an equilateral triangle emitting rays of light. Evans argues that “Rimmer’s drawing makes the difference between concepts of the Trinity clearer. The Christian concept . . . is three persons in one God. Swedenborg is insistent that his version is different: one God with three aspects.” This is “quite literally what is shown in Rimmer’s drawing” (91).

More down to earth, but equally mystical, is Before the Picture (fig. 3), a contemporary interior scene in which a young woman stands contemplating a gold-framed painting that—Evans claims—is the portrait of her husband, “shown standing outdoors against patches of blue sky and wearing a wide-brimmed hat similar to the one worn by Rimmer’s pupil, John La Farge, in his 1859 Portrait of the Painter [Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York]” (98). (La Farge [1835–1910] attended Rimmer’s anatomy lectures in Boston while based in Newport, Rhode Island, in the 1860s.) We have to take Evans’s word for it, since the image is so radically foreshortened that it is difficult to make out. In any event, she interprets the scene as expressive of the Swedenborgian (and contemporary Spiritualist) idea of the separation between our world and the next as a singular dividing veil (97). The husband, “as a deceased person, has developed into his true interior self, which from the light above, means that his destiny has been heaven. The woman, still alive, is necessarily in an exterior state, and this might not be the same as her interior—or spiritually real—self. The moment shown is apparently a critical instance of awareness for her as she looks beyond her valued vase to the supernaturally lit likeness of her husband” (101). However, the wife must reject her materialism—suggested by the apparently new, luxurious furniture and décor—to join him after death.

After offering very close Swedenborgian readings of paintings such as The Gamblers, Plunderers of Castile (1879; Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton), an exotic historical tableau bathed in muddy shadows and amber light, Evans cautions us that while Rimmer used Swedenborgian ideas in his pictures, “he cannot be traced as attending a particular Swedenborgian church, and his beliefs differed from Swedenborg’s in important ways,” for example, in their conflicting views on conscience as God-given (Rimmer) or acquired from religion (Swedenborg). But more importantly, she contends “the way Rimmer most startlingly separated himself from Swedenborg is that, like the English artist William Blake [1757–1827] (also, for a time, a Swedenborgian), Rimmer had his own visions and even talked to angels. Given his own sojourns beyond this world, he did not need Swedenborg as an intermediary” (107). The source for that assertion is the “Stephen and Phillip” manuscript. It is hard to argue that Rimmer did not have conversations with angels, though we only have his word for it. But one has to wonder if such visions were only manifestations of his mental state.

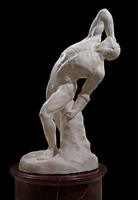

From the realm of the visionary, Evans moves on to solid materiality in chapter 5, “A Challenge to International Neoclassicism,” which deals with Rimmer’s sculptural works. She notes that these works were created largely for exhibition and teaching purposes, in contrast to the paintings, which were seldom shown in the artist’s lifetime. Impressively, Rimmer taught himself to carve, both in marble and in the far more resistant New England granite. While attentive to ancient models like Laocoon and His Sons (Roman copy after original of 2nd century BCE; Vatican Museums, Vatican City), on which Rimmer based his St. Stephen (1860; Art Institute of Chicago), the artist aimed to endow his work with the soul that—according to contemporary views—antique sculpture had left out.

As Evans notes, Rimmer’s extraordinary anatomical expertise was fundamental to the expressiveness of his figures. The tragic Falling Gladiator (fig. 4), which, strange to say, was exhibited in Paris at the notorious 1863 Salon des Refusés thanks to Stephen Perkins, the artist’s friend and patron (one of the very few). So striking was its realism that “several French sculptors” were certain that “parts of it must have been cast from a real person,” though in fact there had been no model of any kind; Rimmer used his own body and his “prodigious memory” to craft the figure (123). Disputing previous interpretations of the Falling Gladiator as associated with the Civil War, Evans suggests that the warrior, with his blunted sword, covertly references Thomas Rimmer (or at least his delusions), who, despite fighting with “all he had,” lost his heritage in the end (124).

One of Evans’s most intriguing analyses concerns the small gypsum figure of a Seated Man, also known as Despair (fig. 5). She avoids the temptation of assuming that this piece too refers to Thomas Rimmer and instead points to the fact that when Rimmer fashioned the statuette he was living in East Milton, Massachusetts, and acting as a physician to the locals, most of them quarrymen. She notes that the man’s forearms “exhibit a condition called vascularity that might be found in body builders or fitness enthusiasts. It might also be found in a quarryman who is accustomed to heavy lifting. The bony enlargement of his knees is another clue to his vocational identity. This could well be osteoarthritis, or wearing of the cartilage and the growth of osteophytes on the side of the knees” (127). This keen and well-informed reading of the figure is compelling, especially because, as Evans points out, Rimmer identified with those who were “disadvantaged or impoverished.” The artist, indeed, mourned one particular “stone layer” whose “arm was blown off and whom he treated for lockjaw. Unable to prevent his death, he described that man’s life as one of ‘miserable woe’” (127).

Rimmer’s portrait sculpture included several renderings of public figures, notably Alexander Hamilton (1864–65, still in situ on Commonwealth Avenue in Boston), and heads of Horace Mann and Abraham Lincoln (1866–67) that, improbably, were created for Argentina’s ambassador and are now to be found in the Sarmiento Historical Museum in Sarmiento, Argentina. The artist also (and unadvisedly) became involved with the American Photosculpture Company, which aimed to produce inexpensive portrait sculpture for people of modest means, using a method similar to the point system in marble sculpture. Unfortunately, a workman stole the bronze figurine of Ulysses S. Grant that was the template for all the plaster casts and thereby demolished hopes that their sale would deliver substantial profits. There were further machinations and maneuvers before the business went bankrupt.

On occasion, as Evans argues, Rimmer’s sculptural work had direct bearing on the real world. The Fighting Lions (by 1871; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York), an essay in the genre of the animalier so successfully practiced in Europe by the French sculptor Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875), whose keen eye for anatomy—bestial in this case—was as acute as Rimmer’s. However, Evans posits that Rimmer’s piece isn’t only about a male lion making a deadly attack on a lioness. “The likely catalyst,” she suggests, “is the women’s suffrage movement and, most especially, the fight for a woman’s right to earn a living wage.” A proponent of women’s rights, Rimmer for several years taught aspiring female art students at the Cooper Union in New York and, unusually for the time, praised women’s ability as artists “as equal to that of men” (147). Fighting Lions, in Evans’s reading, is no mere feral struggle but an “allegory of male tyranny or male dominance gone amok” in the determination to keep women in their place (145). However, the allegory was “too abstruse” to be understood by “people who did not know him,” who, at that time, would have been most of them (147). One wonders if Evans is reading too much into the piece, but her contention is intriguing, nonetheless, and it supports her characterization of Rimmer as a feminist avant la lettre.

Rimmer’s last known sculpture, Torso (1877; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston) is, as Evans asserts, “his most radical and original work” (149). The torso is literally just that: a headless, neckless, armless, and legless trunk. Its blunt monumentality belies its tabletop scale (14 ½ inches in height). Evans suggests the figure of the newly created Adam in Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel fresco as a likely model but adds that, in eliminating the figure’s navel, Rimmer defied Charles Darwin’s theory of the descent of man, thus “showing his Torso was created and not born” (150). Evans also suggests that the Parthenon’s West Pediment figure, tentatively identified as the river god Illisos (438–32 BCE; British Museum, London), was an important source, and indeed Rimmer’s torso is the mirror image of its ancient model.

Chapter 6, “Visionary Depictions,” returns to painting and to the artist’s embrace of Spiritualism, that wildly popular, quasi-religious practice of communion with spirits of deceased loved ones or famous figures from history. Rimmer attended séances where mediums would channel the spirits’ words and thoughts from beyond the grave through trances or automatic writing. Indeed, “eventually, the whole Rimmer family became Spiritualists and habitually used slate chalkboards that a spirit medium would bind together and then untie to reveal a spirit’s written response on one of the boards” (168). Like countless people in the US and Europe in the nineteenth century, Rimmer had more than a nodding acquaintance with death: five out of his eight children died very young, and “he would have wanted to learn about their welfare” in the spirit world. Not surprisingly, he might also have wished to ask the spirits “whether Louis XVI’s son survived.” (169).

The centerpiece of this chapter is Rimmer’s imposingly large landscape painting inaptly titled English Hunting Scene (fig. 6), which was never exhibited but, rather, seems to have been created for private viewing. While on the surface the painting appears to be a dreamlike, medievalizing panorama along the lines of Thomas Cole’s nostalgic before-and-after vistas in The Past—with its medieval castle and jousting knights—and The Present (both 1838; Mead Art Museum, Amherst College, Amherst), with its melancholy ruins, it is, in Evans’s reading, a far more metaphysical effort in which past and present are combined. “It reflects Rimmer’s belief, reinforced by séance experiences, in an afterlife—where one retains one’s identity—and in the related, omnipresent reality of a spirit world” (165). Evans proposes that the two young, modern women in the foreground, possibly Rimmer’s daughters, are accompanied by “an imaginatively dressed spirit guide from the world of the past” who seems to be pointing out the various sights in the middle ground and distance (165). These include male and female horseback riders in vaguely Tudor dress, a couple of dogs, some translucent capering figures, an exotic ruined palace bathed in light on the right, and, on the left, a shadowy stand of majestic trees. Barely visible at the far left is a dark staircase.

Evans regards the “hunting” scene as a multidimensional Spiritualist space in which the artist’s daughters experience an “epiphany that is not available to everyone,” that is, “break-through views to a spirit world that he knew to exist because, as he believed, he had seen and visited it himself. Indeed, the supernatural world he depicted went beyond the Spiritualist preoccupation with the dead to include angels, devils, and fairy-like beings from another realm” (172). Bearing this out, Evans analyzes two drawings—The Midnight Ride and The Demon Feast (both late 1840s; Boston Medical Library, Boston)—in which a mounted man and his little son flee from a bevy of scowling, hideous monsters. In this regard, one of the most fascinating secrets Evans reveals is a conservator’s photograph of Sleeping (ca. 1878; Currier Museum of Art, Manchester), which depicts a little girl, nude and slumbering on fluffy pillows. Painted over now but clearly seen in the photograph is a predatory monster leering at the unconscious child. It is like a prepubescent version of Henry Fuseli’s The Nightmare (1781; Detroit Institute of Arts, Detroit), which Rimmer may have known through widely circulated engravings.

Evans discusses various drawings and paintings with supernatural, demonic, or angelic connotations, including the Head of a Young Woman (1866 and 1867; unlocated), which once included a thick white streak of paint hovering overhead. She references Rimmer’s “Stephen and Phillip” manuscript, in which the artist more than once described a spirit as “a vapor mist or small cloud” and concludes that “strange as it may seem, this indicates that the woman is accompanied by a spirit, and it is potentially in control” (175). Here again is an excellent example of Rimmer’s idiosyncratic symbolic vocabulary. To most of us, the streak would appear to be just that: a smudge of paint. Rimmer-wise, it makes a great deal more sense to regard it as a manifestation of the supernatural.

At the end of the chapter, Evans circles back around to the English Hunting Scene to comment on the “hidden but most revealing component: the profile of an outdoor staircase” at bottom left (185). She connects this anomalous feature to Swedenborg, “who spoke of a staircase connecting the worlds of the living and the so-called dead” (187). The stairway, therefore, is “for the convenience of visiting spirits who might wish to return to their former life” (187). One wonders why any spirit might actually need a physical means of descending and ascending, but presumably Rimmer gave visual form to what would seem, clearly, to serve a metaphorical purpose, like Jacob’s ladder. At the bottom of Rimmer’s staircase, Evans continues, is an “unexplained incandescent spark,” which is “likely a surrogate for the artist. Rimmer wrote of the soul ‘that freed from the presence of the sun and of the world doth then the soul begin to glow, burn of its own fire and shine of its own light’” (187). Given that the spark shines directly above the artist’s signature, Evans’s claim here is entirely convincing.

In the final chapter, “The Death and Legacy of a Maverick Artist,” Evans begins by recounting the artist’s final days and the 1880 memorial exhibition of his paintings and sculptural works at the Boston Museum. She then moves on to a review of the literature on Rimmer, beginning with his first biographer, Truman Bartlett. She maintains that Bartlett was the root cause of misunderstandings that persisted in subsequent studies until, we as readers are to infer, her own righting of their wrongs. Evans argues that Bartlett (not surprisingly) “could not identify the artist’s illness or put it in a larger context. Just as limiting, he did not have sufficient perspective or independence of mind to fully appreciate the older sculptor as an innovator” (198). She also faults Bartlett for “another major error” in failing to grasp “the spiritual meaning that was central to Rimmer’s life and much of his work” (199). All told, and with very few exceptions, notably the inclusion of four of his drawings in the legendary 1913 Armory Show, Rimmer’s oeuvre languished throughout much of the twentieth century. Art historically, he remained an outlier, even though Flight and Pursuit has continued to lure scholars determined to solve the mystery of its meaning.

Ironically, as Evans notes, Rimmer’s large drawing Evening, or the Fall of Day (see fig. 2) was chosen by Led Zeppelin for their record label logo—Swan Song Records—in 1974, and “thereafter and until the present, this now colored image has served as a commercially successful band reference on T-shirts, patches, and tattoos” (203). Having recently seen that selfsame image adorning the T-shirt of some rock band’s front man in a video projected onto the huge screen at the Museum of Popular Culture in Seattle, I can vouch for its longevity. Evans takes a dim view of the fact that this “‘Icarus’ should once have been meant to be the rejected angel Lucifer—light bearer—which is why he lacks genitals and had an otherworldly spark on one wing, is now of little or no consequence” (203). It’s hard to resist the temptation to wonder what William Rimmer might make of his drawing’s posthumous fame.

The sexlessness of Rimmer’s figure, though, does raise issues. One wonders if at some level it’s less a matter of Lucifer’s deficiency (angels are incapable of procreation) than a reflection of the artist’s own sense of lack as a man whose hardscrabble domestic and artistic life was marked by tragedy, poverty, and, in certain cases, failure. Such a question may only reflect our own post-Freudian tendency to superimpose or project contemporary ideas onto figures from the past. But this quibble has bearing on a larger issue, also psychologically charged: Evans’s contention—or conviction—that Rimmer was bipolar and that, accordingly, his work in aggregate charts whatever mental extreme had him in its grip at any particular time. One of the problems in this approach, of course, is that it absolutely eludes any attempt to prove that Rimmer was or was not bipolar. Evans does assert that “art is never a credible basis for a psychiatric diagnosis,” though it “often can be supporting evidence of an artist’s mood” (30). Or can it? Can the works themselves bear the weight of such assumptions? Despite Evans’s qualification, it often seems as if she does base many of her interpretations of Rimmer’s art on a psychiatric diagnosis, which can neither be proven nor refuted in the absence of any concrete evidence.

Although Evans’s account of Rimmer is deep and thorough, she does relatively little with the artist’s anatomical study—he published the highly regarded Art Anatomy in 1877—or teaching. Beyond glancing mentions of contemporaries such as William Morris Hunt (1824–79), she tends to gloss over Rimmer’s place in the nineteenth-century Boston art community. Yes, he did keep his own paintings under wraps, but he certainly was aware of what other artists were doing and was at the very least acquainted with some of the leading figures of the day. Then there is her contention that Rimmer can be regarded as “America’s first modernist sculptor” (202). I suppose this ranking is part and parcel to Evans’s desire to elevate Rimmer to a higher place in the US art-historical pantheon, as is her comparison of Rimmer with Auguste Rodin (1840–1917). But to me, it is probably the least interesting of her arguments. Modernist is a slippery term impossible to pin down; the US art community has been grappling with it now for many years, and still the question is unsettled. Does it really matter if we think of Rimmer as modernist or not?

Ever since his own lifetime, William Rimmer has proved to be a hard nut to crack, but Evans has, indisputably, pried him open wider than any of her predecessors managed to do, however meticulous their scholarship. One of this book’s most significant contributions is the revelation of Swedenborg’s writings as a major source of Rimmer’s inspiration. The author’s careful and erudite reconstitution of the ways in which the eighteenth-century sage’s visionary ideas corresponded with Rimmer’s is a tour de force that, along with the documented impact of Spiritualism, sets the artist firmly into the times in which he lived and worked while always keeping his essential and eccentric individuality in play. However one reckons with Rimmer’s place in, or out of, the canon, he was, as Evans conclusively demonstrates, an artist of unique and uncompromising vision who could work equally well in two and three dimensions. Perhaps his student and admirer, the sculptor Daniel Chester French (1851–1931), put it best: Rimmer’s work “is not like anything else at all” (quoted in Evans, 200). And that, in the end, is what makes it so odd and so compelling.