Prophets, Priests, and Queens: James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament

Reviewed by Stephen BrownStephen Brown

The Jewish Museum

Email the author: sbrown[at]thejm.org

Citation: Stephen Brown, exhibition review of Prophets, Priests, and Queens: James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.18.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Prophets, Priests, and Queens: James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament

Brigham Young University Museum of Art, Provo

May 6–December 31, 2022

Catalogue:

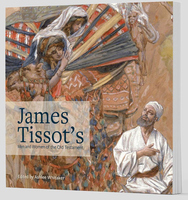

Ashlee Whitaker, ed.,

James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament.

Provo, UT: Brigham Young University Museum of Art, 2022.

278 pp.; 207 color and 101 b&w illus.; endnotes; bibliography; index.

$49.00 (softcover)

ISBN: 9780842500937

In October 1886, at the age of fifty, the celebrated French artist James Tissot (1836–1902) set out from Europe for the Near East to fulfill his plan of illustrating the New Testament. The last sixteen years of the artist’s life were devoted to biblical illustration and to the orientalist and realist goal of documenting the Holy Land in person. Tissot participated in three known tours between 1886 and 1896. By the mid-1890s, the artist had completed 365 watercolor and gouache paintings intended to be reproduced as prints. They differ from earlier invenzione in the history of art, the most famous being the oil-sketches of Peter Paul Rubens, which were the model for countless other works produced as tapestries, paintings, and engravings. Tissot’s paintings were also to be copied, but by advanced photomechanical means rather than by hand. In this case, the published images—at least qua images—would offer simulacra of the paintings. Tissot, conscious of the project’s ultimate goal, referred modestly to his watercolors not by their medium but by their function: dessins originaux (original designs).

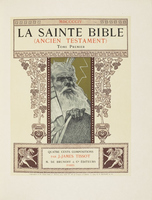

As the end of the century approached, Tissot pushed further, undertaking the ambitious project of illustrating the Old Testament—the subject of the exhibition and catalogue reviewed here. Tissot began the enterprise, but it was completed by six others before its publication in 1904, under the eye of the artist’s business associate, art publisher Maurice de Brunoff (1861–1937). The other artists were noted in the original French Bible, though they are absent from the English edition.[1] In this exhibition and catalogue, their authorship reemerges, constituting a significant development in the scholarship, since earlier literature ignored the variety of hands involved.

In 1900, thanks to public subscription, Tissot’s watercolors for the New Testament were afforded a prestigious home in New York City at the Brooklyn Institute of Arts and Sciences. It was only in February 1909, seven years after the artist’s death, that the original designs for the Old Testament found a buyer in the eminent banker, businessman, and philanthropist Jacob Schiff.[2] In March of that same year, the paintings were gifted to the New York Public Library and, in 1952, transferred to their current location: the Jewish Museum (the former home of Frieda Schiff Warburg, Jacob Schiff’s daughter). Thirty years later, thanks to the efforts of curator Norman Kleeblatt, several of the watercolors were conserved and displayed publicly.[3] But this was four decades ago. Prophets, Priests, and Queens: James Tissot’s Men and Women of the Old Testament—organized by Ashlee Whitaker, Head Curator and Roy and Carol Christensen Curator of Religious Art at Brigham Young University Museum of Art—thus provides a long-awaited and thorough treatment of Tissot’s Old Testament paintings, more than one hundred of which were loaned from the Jewish Museum’s collection for this show. The exhibition title recalls Tissot’s realist intentions, indicated in a rough sketch for a title page: Les hommes et les femmes de la Bible par J. James Tissot (“Men and Women of the Bible by J. James Tissot,” xiii, 9). The exhibition filled several galleries, focusing almost exclusively on the watercolors, which were arranged according to the order in which they appear in the Bible. Just one vitrine included a few sumptuous pages from the published work, and documentation of the artist’s methods was minimal. The emphasis of the display was instead on the inventiveness and exquisite beauty of the paintings and their status as a compelling visualization of scripture.

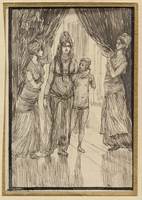

“I am never so happy as when I have . . . years of labor before me,” the artist confided to De Brunoff (xi). Whether from the point of view of aesthetic, spiritual, or pecuniary motives, Tissot’s Bible reappears as a project of epic scope in Whitaker’s account. The necessary productive forces rested on several indispensable pillars: expertise, experience, financing, an indefatigable work ethic, and, if you will, genius. Critical was a naturalist faith in direct observation and representational skill, qualities intensified by a metaphysical engagement with the subject. Such an approach necessitated site visits—a realist pilgrimage, as it were—for verification and documentation of actual locations and people. Supplementing this were the artist’s studies of texts and archaeological artifacts in the Louvre. The essential artistic method involved consummate draftsmanship and the production of small compositional sketches by the master (dessins fait à la plume) in pen and ink. These were followed in turn by the “original designs” executed in viscous, water-solvent pigments (figs. 1, 2). In 1899, Tissot perhaps saw in his mind’s eye five hundred designs in total. By October of that year, 435 of the pen and ink sketches were finished. Two years later, in August 1902, as death closed in, some two hundred of the original designs were ready. In November 1905, during the tour of the original designs in the US, four hundred were counted, and the same number appeared as printed illustrations in the first French edition (1904); the contemporaneous English edition has 396 printed illustrations. On the other hand, the sales catalogue prepared in 1909 for the US market lists 372 watercolors (368 of which now form the Jewish Museum’s collection).[4] Whitaker posits that more than half of the original designs were completed by hands other than Tissot’s. One senses the magnitude of a project that necessitated an industrial division of labor to realize the publication, which incorporated beaux-arts practice, historical and textual research, a painstakingly realist attitude, and travel. Photography assumed several roles, not least in the labors associated with photomechanical printing (fig. 3).[5] Direct observation confronted myth and traditional visions, while academic methods vied with the more recent modes of illustrative reproduction (fig. 4).

The catalogue produced to document this modern istoria is paperbound and lacking the robust binding that might be expected for such a monumental project. Nevertheless, the square trim size (11 x 11 in.) shows to advantage the beautiful reproductions and accommodates both vertical and horizontal pictorial axes. All 129 works loaned for the exhibition are accorded full-page color plates. In the back matter, Whitaker has appended a list (unnumbered) of, “all the currently known Old Testament subjects painted by James Tissot and his assistants” (226–36): 398 original designs, by this count, plus five oil paintings either in private collections or unknown locations. Additionally, Whitaker offers a partially illustrated discussion of the four hundred compositional pen-and-ink sketches that were included with the premier example of the deluxe volume for the English market.

The catalogue contains a detailed chronology of Tissot’s entire life and the work in question as well as a selection of the artist’s correspondence with his publisher. Ellipses indicate numerous omissions, and the original French text is found in endnotes, which renders verification daunting. There is an appendix devoted to the artists who supplied additional drawings, following Tissot’s death in 1902. A bibliography and index complete the catalogue.

Whitaker assigned the reinterpretation of this treasury of material to various scholars, including Sarah Schaefer who establishes Tissot’s work within the context of nineteenth-century biblical illustration (38–49). Schaefer isolates a specific scene from the Book of Daniel, the feast of the neo-Babylonian potentate Belshazzar (6th century BCE). The imagery devoted to this figure of arrogant impiety, subject to divine retribution, is analyzed diachronically across the nineteenth century, during which Schaefer notes the increasing realism and reliance on archaeological discovery. She draws a line from the mezzotint sublimities of John Martin (1789–1854) to the wood-engravings of Gustave Doré (1832–83), whose publications and London exhibitions are identified as Tissot’s major inspiration. Schaefer considers Tissot’s realism within the context of techniques associated with impressionist advances of the epoque, namely the turn away from the staffage of conventional tableaux towards the depiction of immediacy in the action of pictorial agents. The result is an immersive quality, distinct from the theatricality of the past. For all its charm, Tissot’s modernist, visual blasé clearly produces less dramatic results when compared to the romanticism that preceded it, especially when applied to the apocalyptic topos.

David and Ann Seely connect the religiosity of Tissot’s Old Testament visualizations to fin-de-siècle sensibilities—notably Catholic revivalism—and to Tissot’s own religious attitudes. They point to Tissot’s traditional symbolism—as opposed to vanguard aestheticism—and the prefigurations of the life of Jesus in Old Testament narratives.

In yet another revelation, Paul Perrin examines a manuscript—acquired at auction in 2014—in which the artist describes his travels in the Near East, indicating his approach “to illustrating the biblical narrative” (51).[6] The Century Illustrated Magazine had expressed interest in publishing Tissot’s text and printed excerpts in 1899, but the document remains unpublished in its entirety. The artist committed to paper his notes on the landscape, sites, cities, and his journeys, producing a memoir, travel journal, and advice in the manner of a traveler’s guide. Perrin considers that for Tissot and others, the voyage to the Holy Land was often less inspired by “the exoticism of the East” than by a “return to the bedrock of Christianity” (58). Apparently, there had been talk at the time of a castle of Catholic retreat in the Levant—in Tissot’s proposal for the acquisition of a mountain near Jerusalem around 1890—on which to found a studio and colony. Nevertheless, Perrin concludes that Tissot’s text deserves recognition as part of the corpus of “French Orientalist literature” (59), and urges its future publication.

The perplexity of Tissot’s biblical vision—based on a dual concern with both veracity and spirituality—is addressed by Philipp Malzl. Tissot’s search for documentary realism is revealed as beset with anachronisms, not least due to an “orientalist fallacy” that, in 1900, considered Jerusalem the mirror of a period several millennia prior (28). The unraveling of the “conceits” of Tissot’s realism has been adumbrated by Gert Schiff and is extended by Malzl’s reference to the problematic use of archaeological remains, the dependence on other works of art, and even the incorporation of signs (e.g., the Shield of the Trinity). The point is surely not to negate the aesthetic quality of Tissot’s creation, but neither is it just a case of “discrepancies between historical truth and artistic interpretation” (36n35). Malzl’s inquiry raises the dichotomy of an imagery based on convention versus that determined by visual attention to the motif—the ideal and the real. For art historians, the unraveling is part of the quest; but for the devout, critical readings of representation—be they about motifs, images, or texts—may interfere with religious beliefs. Tissot was known to be at pains to indicate the inspired aspect of his art. Painter and pilgrim, he was immersed in the devotional aspects of what he saw and what he was able to represent. This visionary process, which Malzl identifies as “hyperaesthesia” (in Tissot’s case, visual attention raised to the sense of spiritual experience), resembled the synesthetic sensuality of younger, contemporary poets and artists in Paris (30). The only difference was that Tissot was drunk with the “actual.” Inspired by symbolist perceptions and his own masterful realist technique, his quest was fortified and his practice was lent a metaphysical authority.

While the exhibition in Provo centered on the biblical imagery of the original designs rather than the printing enterprise, Krystyna Matyjaszkiewicz’s essay explores the close relationship between the artist and his publisher. Tissot wrote to De Brunoff in August 1900: “I have only you in the world, my dear friend, to love and in whom to hope” (256, 261n14). They became associates in 1894, when De Brunoff was a manager of the famous Lemercier printing establishment. A significant correspondence of over sixty letters dating from 1896 to 1901, from the artist to his publisher, remains extant. Work on the Old Testament with De Brunoff was underway by 1899, and the publisher established his own company in 1901. Matyjaszkiewicz proposes a series of differences between the aims of the artist and the publisher. De Brunoff is accused of posthumously betraying Tissot by not publicizing the names of the other artists involved, though this seems more a betrayal of the other artists than of Tissot. Furthermore, there may have been disagreement concerning the propriety of representing God visually, with Tissot in favor of visualization. Some thirty images may have been excised because they illustrated books of the Bible that Catholicism accepted and Protestantism did not. Matyjaszkiewicz believes the omission may stem from the divergent religious viewpoints of the artist and his publisher, though it may also reflect audience expectations. Editorial cuts were made to the illustrations of the English volume and not to the French, possibly from a fear that nudity and violence might run contrary to the taste of the late Victorian market. On the other hand, an accelerated publication schedule, according to Matyjaskiewiecz, led to regrettable transgressions of the mise-en-page, namely the frequent distancing of the illustrations from the pertinent text. Ultimately, the author feels that the publication was “not in keeping with Tissot’s vision, particularly in the layout of pictures, and lack of distinct thematic cohesion and supporting commentary” (13–14).

This exhibition and accompanying catalogue add greatly to our knowledge of a fascinating contribution to the history of biblical representation and to the artistic achievements of Tissot and his collaborators. Visitors can certainly rejoice that, as Matyjaskiewiecz concludes, “Despite the drawbacks, De Brunoff’s efforts did allow for the realization of Tissot’s important series in gouache as well as in printed format” (13–14). For Tissot, the journey that led to the published volumes may have been as significant, if not more so, than the result. For viewers today, the initiative of Whitaker and Brigham Young University Museum of Art provides a foundation for further study of “the ambiguous modern,” James Tissot, and a welcome occasion for the wider appreciation of this major artistic project.

Notes

I take this occasion to recall the teaching of a scholar who devoted his career to British and American art, and who maintained a fond interest in the artist Tissot, Allen Percival Green Staley (1935–2023). In lumine tuo, videbimus lumen.

[1] J. James Tissot, La sainte bible (ancien testament): quatre cents compositions par J. James Tissot, 2 vols. (Paris: M. de Brunoff et cie., 1904); J. James Tissot, The Old Testament, Three Hundred and Ninety-Six Compositions Illustrating the Old Testament, 2 vols. (Paris: M. de Brunoff Art Publisher, 1904). The French edition was numbered 1 to 560. The list of other artists is confined to one sheet in the backmatter of the second volume under “Note de l’éditeur.” Whitaker includes a list of “Contributing Artists” in the exhibition catalogue. The other contributors, in descending order by number of contributions, were Michel Simonidy (1870–1933); A. de Parys (1885–1936); Charles Hoffbauer (1875–1957); Georges Scott (1873–1943); Auguste François-Marie Gorguet (1862–1927); Henri Jules Ferdinand Bellery-Desfontaines (1867–1909).

[2] See “Catalogue of 372 Watercolors of the Old Testament by J. James Tissot,” American Tissot Society (New York, London, Paris, [1909]). After an unsuccessful auction, Tissot’s paintings were privately purchased by Jacob Henry Schiff (1847–1920) for $37,000. Although a practical proposition, roughly $100 per design, it was likely a loss for De Brunoff (the public subscription for the New Testament designs had raised $60,000). See Whitaker, xviii; and Matyjaszkiewicz in Whitaker, 20n156. The Society was established to handle the US market and was dissolved by bankruptcy on January 31, 1909.

[3] Yochanan Muffs and Gert Schiff, J. James Tissot, Biblical Paintings (New York: The Jewish Museum, 1982).

[4] Five of the original designs that were not included in the English edition as illustrations are in the collection of the Morgan Library, New York. Whitaker proposes that for the Old Testament, Tissot was the sole author of 160 original designs while others were responsible for 240. This accords with De Brunoff’s list.

[5] The dependence of Tissot’s project on photographs was more extensive than has been demonstrated to date. None are reproduced in the present work save for the item that adorns the back cover. Preliminary reconnaissance of this lacuna took the form of an address delivered at the Tissot symposium in Provo: “Deus ex machina: Tissot and Photography”—with grateful appreciation for the Museum of Art’s indulgence of such a lecture, rife with speculation. Cf. Anne Labourdette, “James Tissot et la photographie,” in James Tissot et ses maîtres, ed. Cyrille Sciama (Nantes: Musée des beaux-arts de Nantes, 2005), 104–05.

[6] James Tissot, "Voyage en Orient," autograph ms, n.d. (ca. 1898–99), NUM MS 824, Collections Jacques Doucet, Bibliothèque de l'Institut National d'Histoire de l'Art, Paris, https://bibliotheque-numerique.inha.fr/.