New DiscoveriesFrançois Henri Jacquet’s Plaster Cast of the Venus of Milo, 1821

by Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer

Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer

Professor of Art History Emerita

Department of Art History

University of Delaware

Email the author: nina[at]udel.edu

Citation: Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, “François Henri Jacquet’s Plaster Cast of the Venus of Milo, 1821,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.5.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

You come to revive our waning aspirations.

To heal the sighs of the hearts you subdue;

You come, having lost only your graceful arms,

To embody the Ideal that never embraces.

—Sully Prudhomme, “Devant la Vénus de Milo”

It was a tense moment on January 24, 2024, in the packed room of the Paris auction house Artcurial, when the auctioneer, Maxence Miglioretti, sounded the final tap of the gavel to announce the winning bid for the most anticipated art object of the day. It was, curiously, a plaster cast (fig. 1) of the celebrated Venus of Milo owned by the Musée du Louvre. King Louis Philippe had ordered the cast in 1830 and offered it as a gift to Lodoïs de Martin du Tyrac, comte de Marcellus (1795–1861), the man responsible for obtaining the original marble statue of Venus of Milo for France in 1821 (fig. 2). The plaster copy had remained at the Château Marcellus near Bordeaux until the sale in 2024, when it was acquired by the Louvre for the substantial sum of 57,728 euros, including the premium. That story, coupled with the origin of the cast itself, which was produced from a mold made more than two hundred years ago in the museum’s own atelier de moulages (casting studio), lent added value to the plaster statue that otherwise might have garnered only a fraction of the selling price.

Marcellus and the Venus of Milo

The story of the discovery of the Venus of Milo takes us back to the 1820s and to Greece under Ottoman occupation. On April 8, 1820, a Greek farmer named Giorgos, working in his field on the Greek island of Milos, part of the Cyclades islands at that time, dug out two carved marble blocks belonging to an ancient sculpture representing a bare-breasted female figure, along with other broken marble pieces, including two herms. The arms and one foot of the female figure were broken off and missing, but one of her hands holding an apple was found nearby, prompting her identification as Venus.

Three young Frenchmen eagerly followed the news of its discovery. All three belonged to the diplomatic mission dispatched to the Ottoman Empire by France. They were Olivier Voutier (1796–1877), a twenty-four-year-old naval officer from the French warship L’Estafette; the twenty-five-year-old comte de Marcellus (hereafter, Marcellus), secretary of the French embassy in Constantinople; and Jules Sébastien César Dumont d’Urville (1790–1842), a thirty-year-old lieutenant in the French navy and future world explorer, cartographer, and botanist. The three arrived at the excavation site at different moments. Voutier was first on the scene. In his notebook, he sketched the marble pieces as they were being unearthed, one by one (fig. 3). Next came Dumont d’Urville, who hurried to bring the news to the French embassy in Constantinople and to alert its secretary, Marcellus. Marcellus hastened to board a warship bound for Milos and arrived just when a heated altercation about the selling price of the sculpture was taking place between the farmer Giorgos, who was supported by the locals; the French envoys; and a potential Greek buyer. Marcellus resolved the issue. He bought the sculpture and took it back on his ship to Constantinople. Once there, he delivered it to his superior, Charles François de Riffardeau, marquis de Rivière, French ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, who in turn sailed to France and offered the Venus as a gift to King Louis XVIII. The king (after a superficial glance at the monument) donated the sculpture to the Musée Royal, now the Musée du Louvre.

All three travelers to the Milos excavation—Voutier, Dumont d’Urville, and Marcellus—were amateur archaeologists and left written accounts of their role in the discovery, albeit with contradictory information. The account of Marcellus in 1839 pulsates with enthusiasm and self-pride and claims the full glory of the discovery while also erroneously attributing Voutier’s drawings of the statue to Dumont d’Urville. Dumont d’Urville, in turn, who arrived before Marcellus, declared himself to be the man who found the Venus for France. Voutier, who was in fact the first Frenchman at the excavation site, was the last to publish his memoir, dated from 1874. In it, he accuses Marcellus of distorting reality and deliberately creating une oeuvre fantaisiste (an imaginary artwork).[1]

Of the three, it was Marcellus, largely because of his distinguished birth and position, who went down in history as the one who obtained the sculpture for France. His portrait of 1825 by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres (1780–1867) shows him as a handsome man of aristocratic demeanor (fig. 4). A diplomat and a royalist who supported the restored Bourbon monarchy, Marcellus was an ideological and cultural hybrid, immersed in the West’s classical past while also fascinated by Near Eastern culture. According to his biographer, Gonda van Steen, he exemplified the period’s intersecting interests in Hellenism and Orientalism, West and East.[2] Indeed, rescuing the Venus from Ottoman-occupied land was, in Marcellus’s mind, a patriotic duty and part of France’s “civilizing mission” on behalf of the enlightened European West. After five years in the Orient and a transfer in 1822 to the French Embassy in London as a secretary to François-René de Chateaubriand (1768–1848), the French ambassador and militant philhellene, Marcellus’s career was cut short when the July Revolution of 1830 replaced the Bourbon rule with the junior Orléans branch of the monarchy. The plaster cast offered to Marcellus by Louis Philippe, the new king, is the very one that was auctioned at the Artcurial sale. Venus stands on a pedestal engraved with an inscription composed by Charles Othon Frédéric Jean-Baptiste, comte de Clarac (1777–1847), archaeologist, artist, and curator of antiquities at the Louvre, referring to the original marble statue it reproduces: VENUS VICTRIX / RAPPORTÉE DE MILO EN 1820 PAR LE / VICOMTE DE MARCELLUS / DONNÉE AU ROI PAR LE MARQUIS DE RIVIÈRE / AMBASSADEUR À CONSTANTINOPLE / ET PAR LE ROI A LA FRANCE (Venus Victorius / brought from Milos in 1820 by / the viscount of Marcellus / donated to the King by the Marquess of Rivière / Ambassador in Constantinople / and by the King to France).

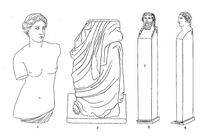

Uncertainty and ambiguity have surrounded the famous statue ever since its discovery. Was this an effigy of Venus or of the sea goddess Amphitrite? Was it Sappho or was it a Muse? Attributions to its makers were constantly shifting too. Was the sculpture by the hand of Phidias, or was it by Praxiteles? Or what about Lysippus? Speculations about the ancient models that might have inspired the effigy abounded. They included the Venus of Cnidus by Praxiteles (4th century BCE; Museo Clementino, Vatican) and the Venus de’ Medici (attributed to Cleomenes, 1st century BCE; Galerie degli Uffizi, Florence), among others. Proposals for restoration came and went, such as the one by the archaeologist and philosopher Félix Ravaisson (1813–1900), who in 1892 conceived a plaster couple representing the Venus of Milo next to Mars (fig. 5), the latter figure based on the prototype of Ares Borghese.[3] Scholars and museum curators debated about the figure’s (vanished) arms and left foot, wondering if there should be a restoration at all or if the statue should be kept in its original, mutilated state.[4]

The many uncertainties about the sculpture were unwittingly reflected in its ever-changing location in the Louvre. Initially placed in the Salle du Tibre, it was moved to the Salle d’Isis and from there to the Salle de la Vénus de Milo. During the two world wars it was temporarily moved from the museum to more secure settings. In 1964 it was exhibited in China and Japan (during the overseas transport to Japan the plaster joint that connected the torso with the lower body of the statue crumbled, a fact that caused huge protests in France and throughout the world).[5] Today the Venus is back in the Salle de la Vénus de Milo where it stood in April 1822, positioned at the center of an arched niche made of dark red marble and flanked by marble sculpture fragments set in two niches (see fig. 2).[6]

The Plaster Cast

As soon as the Venus of Milo reached the Louvre, in April 1821, a casting mold of the statue was produced by François Henri Jacquet (1778–after 1848), one of the master molders in the museum’s atelier de moulages founded in 1794.

Since late antiquity, plaster casting of artworks, and of valuable objects more generally, including the features of deceased individuals known as facsimile portraits, was common practice,[7] and remained so throughout the Middle Ages and the Renaissance and Baroque periods.[8] The practice became institutionalized in the eighteenth century, when casts, in addition to being widely used in teaching at art academies, were also exhibited in museums and private collections. Between 1797 and 1838, the Danish neoclassical sculptor Albert Bertel Thorvaldsen (1770–1844) formed a collection of 657 casts, displayed in a private museum whose planning he had supervised in person. He bequeathed the museum, located in the vicinity of the Danish royal palace, along with his studio to the city of Copenhagen in 1838 (fig. 6).[9] Another such collection of casts of celebrated sculptures in the 1790s was that of the wealthy sculptor Jean-Baptiste Giraud (1752–1830), on public view in his townhouse on the place Vendôme in Paris and referred to as “the first historical museum of comparative ancient sculpture that France ever owned.”[10]

In time, museums started adding plaster copies of antiquities from diverse countries, ethnic groups, and cultures to their collections of original artifacts, giving their exhibits new transhistorical, art historical, and educational dimensions.[11] By the mid-nineteenth century, major museums, including the British Museum and the South Kensington Museum (known now as the Victoria and Albert Museum), the Berlin museums, the Louvre, and the Musée National des Monuments Français, then known as the Musée de Sculpture Comparée of the Trocadéro (inaugurated in 1882), relied primarily on casts in order to compensate for their collections’ international deficiencies and to expand their historical span.

Collections of plaster casts in museums revealed worldwide developments in sculpture and architecture, from antiquity to the present. As one art critic reflected in 1852, the notion of art’s universality had become an utmost necessity for modern museums: “A museum should give a perfect view of the history of art in every civilized nation. It should be a collection of all those monuments on which the artistic instinct of bygone centuries has exerted itself. It should contain all the important documents of the plastic power of mankind. . . . When we cannot attain this object by marble and brass, we should make up the deficiency by way of casts.”[12]

As the popularity of rapidly reproduced foreign artworks grew, the need for additional museum space grew as well, prompting directors and curators to consider creating independent museums of plaster casts. Founded in the 1830s, the plaster-cast collection of the Neues Museum in Berlin became the largest and most important cast collection in Europe. In 1856 the museum decided to create a separate “cast museum” that would assemble all plaster casts on a single floor. The exhibits were organized in chronological order within four broad subject areas: Greek art, Roman art, medieval art, and Renaissance art.[13]

In France, the need for a museum of plaster casts was also frequently expressed, though it was long in the making. It was mentioned repeatedly since 1820 by the Director of Museums, comte Auguste de Forbin, who launched two molding campaigns abroad, in England and in Italy. In 1817 he proposed to mold the Parthenon marbles brought to the British Museum by Lord Elgin (1766–1841), a project that was eventually executed, and the copies arrived in France in 1819.[14] Forbin’s wish for a museum of plaster casts materialized several years after his death in 1841, thanks to the initiative of the Inspector General of Higher Education, Ravaisson. In 1860, Ravaisson, a longtime advocate of the benefits of plaster casting, organized an enormous display of casts at the Palais de l’Industrie, borrowed from museums all over Europe and representing all stages of ancient Greek art, from Archaic to Hellenistic (as well as some Roman exhibits).[15] The purpose of this tour de force was both archaeological and pedagogical. As the art critic Étienne Michon wrote, underlining both the aesthetic and the educational mission of the exhibition, “the artworks are [best] seen for themselves rather than through written reports. It is from them [the artworks], and not from written documents, that we perceive their worth.”[16]

As a consequence of the extraordinary success of his show, Ravaisson was appointed Conservateur des antiques et de la sculpture moderne (Curator of Antiquities and Modern Sculpture) at the Louvre in July 1870. The time was ripe to realize his ambitions. In 1874, he published a written outcry in the Revue des deux mondes in an article titled “Un musée à créer” (A museum to be created).[17] He opened his essay by complaining that although France’s collection of sculptures at the Louvre was among the largest in the world, it lacked an important component: an ensemble of plaster casts that offered a worldwide overview of the history of sculpture to visitors—an ensemble that would be easy to obtain, he stressed, and that numerous European museums, in London, Berlin, Dresden, Bonn, and Zurich, already possessed. For “it would be most interesting to bring together along with the original masterpieces that we already own, the accurate reproductions of those that are dispersed throughout the entire world. . . . This being so, how useful would be a collection in which we could see, translated into impeccable facsimiles, all that has been preserved for us, but is disseminated all over [the world].”[18]

Along with the expansion of displays of plaster casts went the emergence of professional plaster-cast workshops. The casting workshops of the Berlin museums and the British Museum were located in their basements. The one at the Louvre was also located within the parameters of the museum (today it is located in the outskirts of Paris). Early on, the studio at the Louvre was led by three master molders—Jean André Getti, Jacquet, and Étienne Micheli (1770–ca. 1845)—who executed both official museum commissions and orders received from the private sector.[19] Plaster became central to the creative process for both the mold and the casts, gradually replacing old-fashioned molding materials such as argyle and wax.[20]

Among the first precious artworks to be cast in plaster in France was the statue of Venus of Milo. In 1822, a year after the Louvre acquired the Venus, a cast of it was sent to the Berlin Academy. In the 1850s another cast was displayed at the Crystal Palace in London. A full plaster copy of the Venus was featured in Giraud’s collection on the place Vendôme.[21] By the middle of the nineteenth century, plaster casts had become extremely popular. Improvements in casting techniques allowed for multiple copies, which lowered costs. Casts of the Venus were produced in two versions: copies of the full statue and of its torso alone. Eventually, the Collas process allowed for making reduced copies of statues, which then, in turn, could be cast in plaster and other materials, including, in the twentieth century, plastic. Thus, everyone could own their own Venus in a size and material they could afford (fig. 7). Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny ironically referred to the statue’s soaring popularity along with its declining dignity when they described it as the “most famous [artwork] in the world . . . on sale in white plastic in the gift shops of Athens and everywhere else” while also quoting the words of Geoffrey Grigson, who declared in his book The Goddess of Love that his readers would be repelled by the “chill giantess in the Louvre.”[22] Haskell and Penny’s sentiment finds an echo in Salvador Dali’s plaster sculpture Venus of Milo with Drawers (1936; Art Institute of Chicago), in which the goddess has become as commonplace as a chest of drawers.

Eugène Delacroix and the Venus of Milo

Like other classical Venus figures—the Venus de’ Medici or the Venus of Capua (2nd century; Archaeological Museum, Naples)—the Venus of Milo inspired quite a few nineteenth-century artists, such as, in France, Théodore Chassériau (1819–56), Carolus-Duran (1838–1917), and especially Paul Cézanne (1839–1906). During his visits to Paris from his native Aix-en-Provence, Cézanne spent time in the Louvre filling his sketchbooks with drawings of classical and Baroque sculptures including sketches of the Venus of Milo seen from a variety of viewpoints (fig. 8). An additional and important proof of the impact of the Venus of Milo that has so far escaped the attention of art historians is Eugène Delacroix’s (1798–1863) July 28, 1830: Liberty Leading the People (fig. 9), exhibited at the Salon of 1831. In the painting, Liberty is personified as a heroically sized, handsome woman whose tunic has slipped off her shoulders to reveal her bare breasts. She is striding over the barricades and raising the tricolor flag, emboldening the rebel masses of the July Revolution of 1830. Formal affinities link her to her classical antecedent, the Venus of Milo: her firm, naked breasts; the position of her arms, one raised, the other lowered; the angle of her face, turned toward her followers; and the folds of her tunic sliding from her hips diagonally between her legs, revealing a single bare foot. Antiquity has come alive in modern times. The spirit of Liberty breathes life into its marble prototype.

Delacroix’s longtime passion for liberté (liberty) resonates in the early entries of his journal. When the war of independence broke out in Greece, he was already in search of subjects that would promote the Greek cause of freedom. His philhellenic feelings were shared by his liberal friends, such as the philosopher Victor Cousin (1792–1867), and members of his family. Through the nephew of his brother-in-law, Raymond Jean-Baptiste de Verninac de Saint-Maur, a lieutenant in the French navy and a fervent philhellene, he met colonel Voutier, one of the first Frenchmen to have seen the Venus of Milo. On January 12, 1824, when he was still working on his Massacres of Chios (1824; Musée du Louvre, Paris), Delacroix wrote in his journal that he had had lunch with Verninac de Saint-Maur and Voutier.[23] The colonel had just returned to Paris after two years of fighting on the side of the Greek forces, led by the renowned Greek chieftains Colocotroni, Ypsilanti, Mavrokordato, and Markos Botzaris as well as the female chieftain Bouboulina, who became his close companions.[24] Back in France, he wrote his Mémoires du colonel Voutier sur la guerre actuelle des Grecs (Memories of Colonel Voutier about the current war of the Greeks), published in 1823. An elated Delacroix listened devotedly to Voutier’s heroic achievements. In his journal the artist recorded episodes witnessed by Voutier, such as that of a Greek warrior holding the Greek flag and treading on the body of a defeated Turk while crying “Zito i Eleutheria” (Long live Liberty). Voutier’s account of the Turkish massacre on the island of Chios further heightened Delacroix’s enthusiasm for his painting intended for the Salon of 1824. Did Voutier also talk about his “discovery” of the Venus of Milo, the epicenter of public attention at the time? Did he show the painter his drawings of the statue? Did Delacroix, whose teacher Guérin worked closely with the Louvre’s curator the comte de Clarac, have access to the marble sculpture?

A set of preparatory drawings, with dates ranging from 1821 to 1830,[25] reveals the evolution of Delacroix’s conceptual thinking about the Venus as the embodiment of the spirit of liberty, beginning with a Venus-like figure of a rebellious Greece in a classical tunic rising triumphantly on a pedestal (fig. 10); to a Venus-like figure of a pleading Greece, on her knees among the ruins of Missolonghi, in a painting shown at the Salon of 1827 (Musée des Beaux-Arts de Bordeaux); and finally to a Venus-like figure of Liberty as the female leader of the French insurrection of 1830, wearing the Phrygian bonnet of 1789 (fig. 11), thus symbolically linking the libertarian struggles of 1789, 1821, and 1830.

In his review of Delacroix’s Massacres of Chios at the Salon of 1824, the art critic Auguste Jal intuitively perceived the libertarian core that linked antiquity and the present, a thread of thought that also weaves together Delacroix’s series of drawings and sketches for Greece/Liberty: “Ancient Greece will emerge from the ruins under which the power of the scimitar has held her prisoner for so long. Then triumphant Liberty, whose accomplice in victory will be the God of War [Mars], will accuse you [the indifferent nations] in the presence of the Eternal One [God].”[26]

Notes

Epigraph: “Tu viens régénérer l’aspiration lasse. / Guérir des vils soupirs les coeurs que tu soumets; / Tu viens, de tes bras seuls ayant perdu la grâce, / Figurer l’Idéal qui n’embrasse jamais.” Sully Prudhomme, Œuvres de Sully Prudhomme, Poésies 1879–1888 (Paris: Alphonse Lemerre, 1888), 36.

All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

[1] Quoted in Andrea de Lorris, ed., Enlèvement de Venus: Dumont d’Urville, Marcellus et Voutier (Paris, Éditions La Bibliothèque, 1994), 96.

[2] Gonda van Steen, Liberating Hellenism from the Ottoman Empire (New York: Palgrave MacMillan, 2010), 6.

[3] Félix Ravaisson argued that the Venus may have been part of a sculpted group that also included a statue of Mars, as seen on several marble ensembles in various museums: “More than twenty extant repetitions, more or less complete, of the type represented by our statue can be counted: from which it can be deduced that there must have existed a famous and classic prototype.” “The Venus of Milo,” in Félix Ravaisson, Selected Essays, ed. Mark Sinclair (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2016), 201.

[4] Jean-Luc Martinez, La Vénus de Milo (Paris: El Viso, 2022), 60–76.

[5] Martinez, La Vénus de Milo, 74.

[6] Martinez, La Vénus de Milo, 95.

[7] According to Laura Jacobus, the Italian painter Cennino Cennini (1360–1427) applied this technique to more than just human subjects, “so that this plaster cast could subsequently be reproduced by a foundry master in precious materials, and hence become a finished precious object that a patron might find desirable.” Laura Jacobus, “‘Propria Figura’: Facsimile Portraiture in Italian Art,” The Art Bulletin 99, no. 2 (June 2017): 97n21. The practice of making plaster casts and copies after antique artworks is traced back to the seventeenth century in Francis Haskell and Nicholas Penny’s Taste and the Antique: The Lure of Classical Sculpture, 1500–1900 (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1981), chaps. 11–12.

[8] See the published papers of an international conference held at the University of Reading in 2006 in Rune Frederiksen and Eckart Marchand, eds., Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present (Berlin: De Gruyter, 2010). See also Ann Compton, review of Plaster Casts: Making, Collecting and Displaying from Classical Antiquity to the Present, ed. Rune Frederiksen and Eckart Marchand, Burlington Magazine 153, no. 1300 (2011): 481.

[9] Jan Zahle, Thorvaldsen: Collector of Plaster Casts from Antiquity and the Early Modern Period (Aarhus, Denmark: Aarhus University Press, 2020).

[10] “le premier musée historique de la sculpture antique comparée que la France ait possédé.” Meredith Shedd, “A Neo-Classical Connoisseur and His Collection: J. B. Giraud’s Museum of Casts at the Place Vendôme,” Gazette des beaux-arts, ser. 6, vol. 103 (June 1984), 201.

[11] As Florence Rionnet notes in her excellent study L’atelier de moulage du musée du Louvre (1794–1928) (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1996), 2–4, casts or moulages are seen everywhere today as safe substitutes for originals. Gypsothèques (displays of plaster casts) can be found in the National Gallery of Edinburgh and the Victoria and Albert Museum in London; in the Czech Republic; in Copenhagen; and at several German universities. Books, articles, and conferences on the subject of plaster casts also abound.

[12] Ferenc Pulszky, “On the Progress and Decay of Art; and of the Arrangement of a National Museum,” The Museum of Classical Antiquities: A Quarterly Journal of Ancient Art 2, no. 5 (March 1852): 12–13.

[13] Émile Michel, “Les Musées de Berlin,” pt. 1, “L’organization des musées–les musées de moulage et de sculpture,” Revue des deux mondes, January 15, 1882, 420–45.

[14] Forbin’s wish was echoed in 1855 and again in 1879 by the architect Eugène Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc (his wish came true shortly after his death). See Michel, “Les Musées de Berlin,” pt. 1, 424–25.

[15] Meredith Shedd, “Phidias in Paris: Félix Ravaisson’s Musée Grec at the Palais de l’Industrie in 1860,” Gazette des beaux-arts, ser. 6, vol. 105 (April 1985), 155–70. The French were doubtlessly inspired by the display of 425 casts of Greek sculptures at the International Exhibition in London of 1854.

[16] “Les oeuvres d’art sont considérées en elles-mêmes, bien plus qu’à travers les témoignages écrits. À elles, non aux textes, on demande ce qu’elles valent.” Quoted in Shedd, “Phidias in Paris,” 165.

[17] Félix Ravaisson, “Un musée à créer,” Revue des deux mondes, March 1, 1874, 232–40.

[18] “Il y aurait un grand intérêt à réunir, à côté des chefs-d’oeuvres que nous possédons en originaux, des reproductions exactes de ceux qui sont épars dans le monde entier. . . . Celà étant, quelle utile collection que celle où l’on verrait, traduit dans des fac-simile irréprochables, tout ce qui nous a été conservé, mais qui est disséminé de toutes parts.” Ravaisson, “Un musée à créer,” 233.

[19] During the Revolution of 1789 and the Restoration, the Louvre’s molding studio catered both to the museum and to the public. In the 1850s, this hybrid system came entirely under the control of the museum’s administration. In 1921, the studio was once again open to a commercial clientele that secured its survival. Rionnet, L’atelier de moulage du musée du Louvre, 9, 24–29.

[20] Rionnet, L’atelier de moulage du musée du Louvre, 34–45.

[21] Shedd, “A Neo-Classical Connoisseur and His Collection,” 201.

[22] Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique, 330; and Geoffrey Grigson, The Goddess of Love, 2nd ed. (London: Quartet Books, 1978), cited in Haskell and Penny, Taste and the Antique, 330.

[23] Eugène Delacroix, Journal, vol. 1, 1822–1857, ed. Michèle Hannoosh (Paris: José Corti, 2009), 112–13.

[24] Olivier Voutier, Mémoires du colonel Voutier sur la guerre actuelle des Grecs (Paris: Bossange, 1823). Voutier had taken part in several battles of the Greek war which Delacroix lists in his journal, including the siege of Athens and the fire of the Turkish frigate in the harbor of Psara, set by the Greek chieftain Constantine Canaris (mistakenly cited as “capitaine Georges”). Delacroix, Journal, vol. 1, 112–13.

[25] Hélène Toussaint was the first to study Delacroix’s drawings inspired by the Greek war, although she did not connect them to the Venus of Milo. Hélène Toussaint, La Liberté guidant le peuple de Delacroix: Les dossiers du département des peintures (Paris: Éditions de la Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1982), 9–29. See also Nina Athanassoglou-Kallmyer, French Images from the Greek War of Independence, 1821–1830: Art and Politics under the Restoration (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989).

[26] “La Grèce ancienne surgira de dessous les décombres où la force du cimeterre l’avait si longtemps retenue. Alors, la liberté triomphante, qui aura le Dieu des armées complice à ses succès, vous accusera aux pieds de l’Éternel.” Auguste Jal, L’artiste et le philosophe: Entretiens critiques sur le Salon de 1824 receuillis et publiés par A. Jal (Paris: Ponthieu, 1824), 49.