Romanticism’s Avatar: Le Rageur of the Forest of Fontainebleau

by Patricia MainardiPatricia Mainardi is professor emerita of art history at the doctoral program in art history of the City University of New York. A specialist in European art of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, her books include Art and Politics of the Second Empire: The Universal Expositions of 1855 and 1867; The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic; Husbands, Wives and Lovers: Marriage and Its Discontents in Nineteenth-Century France; and Another World: Nineteenth-Century Illustrated Print Culture, in addition to numerous articles, catalogues, and reviews. She has received numerous fellowships, including the National Endowment for the Humanities, the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts at the National Gallery of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the American Council of Learned Societies, the Institut National de l’Histoire de l’Art (France), and the Yale Center for British Art. She is Chevalier in the Ordre des Palmes Académiques of France, and is one of only two art historians who received both the College Art Association Distinguished Teaching of Art History Award and its Charles Rufus Morey Award for the most distinguished book of the year, Art and Politics of the Second Empire.

Email the author: pmmainardi[at]gmail.com

Citation: Patricia Mainardi, “Romanticism’s Avatar: Le Rageur of the Forest of Fontainebleau,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.4.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

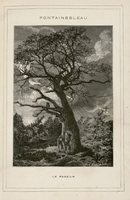

In 1843, Victor Hugo (1802–85) wrote: “Trees of the forest, you know my soul!”[1] His contemporaries would agree with him, especially for the tree that many felt best expressed their soul, an ancient oak in the Forest of Fontainebleau called Le Rageur (the Raging One) (fig. 1). It was so esteemed that when it died in 1904 it was accorded an obituary in the Paris press. And yet today it is virtually unknown, overtaken in art historical discourse by the Bodmer Oak, a neighboring tree in the Forest of Fontainebleau that was painted by the Swiss/French artist Karl Bodmer (1809–93) and later by Claude Monet (1840–1926) (figs. 2, 3).[2] That tree, however, was unfamiliar to contemporaries; neither Bodmer nor Monet exhibited works representing it under that title, and it never commanded the affection that so many artists and writers felt for Le Rageur. If trees can be said to express the soul of a nation, then the contorted Le Rageur is the avatar of the Romantic era in France, while the relatively impassive Bodmer Oak might represent Impressionism. This article is an attempt to reinsert the motif of Le Rageur into the history of nineteenth-century art and culture, and will, I hope, lead to the identification of additional works and expand our understanding of how landscape painting can function as carrier of the zeitgeist of a period.

Numerous contemporaneous references suggest the resonance that Le Rageur held for contemporaries. Indeed, the successive representations of Le Rageur constitute an example of the layered accumulation of cultural meanings akin to what Frederic Jameson has called “wrapping.”[3] The tree’s twisted, gnarly branches straining upward encouraged anthropomorphic readings in a way that the Bodmer Oak’s easy ascent never did, and perhaps that is why Le Rageur captured the attention and imagination of contemporaries. Its resonance in art, literature, and politics enabled it to function metaphorically even after its demise. I will not suggest a unitary significance to the imagery of this tree, because, instead, there was a constellation of meanings “wrapped” around Le Rageur, that made it not only the best-known tree of nineteenth-century France but, indeed, the avatar of the Romantic era.

Le Rageur was not unique in bearing cultural significance, for the symbolism carried by trees is embedded in the Western tradition: the laurel tree was sacred to Apollo just as the linden was the tree of Aphrodite; cypresses connoted the underworld, and willows signified (and still do) mourning and sadness.[4] The oak, however, was always the mightiest of trees, the tree of Zeus and, later, Jupiter, father of all the gods. Surely, it was not coincidental that the two named trees celebrated by nineteenth-century French artists were both oaks, for the oak was revered throughout the Western world for its age and hardiness. In the first century BCE, the Roman poet Virgil in his Aeneid explicitly compared his hero Aeneas to an aged oak tree:

As when, among the Alps, north winds

will strain against each other to root out

with blasts—now on this side, now that a stout

oak tree whose wood is full of years: the roar

is shattering, the trunk is shaken, and

high branches scatter on the ground; but it

still grips the rocks; as steeply as it thrusts

its crown into the upper air, so deep

the roots it reaches down to Tartarus:

no less than this, the hero; he is battered

on this side and on that by assiduous words;

he feels care in his mighty chest, and yet

his mind cannot be moved; the tears fall, useless.[5]

The oak had especial significance in France, because, in addition to its classical heritage, it was revered by the Druids and Gauls. The art critic Théophile Thoré (1807–69) called it “the sacred tree, representing strength and longevity, the national tree that served as the natural cathedral of our ancestors for the celebration of their religious rites.”[6]

This cultural veneration of trees found its echo in visual art. Since the landscape genre was not taught at the École des Beaux-Arts, aspiring artists had to learn its rudiments either through training with one of the esteemed historical landscape painters—Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875) studied with Victor Bertin; Théodore Rousseau (1812–67) with Charles Rémond—or by studying one of the numerous landscape-drawing manuals published from the late eighteenth through the nineteenth centuries. The competition for the Prix de Rome in historical landscape painting even required the completion of a “tree portrait” whose species was announced only that day, requiring young artists to become familiar with all the major species.[7] Just as academic training required students to draw the human figure, first nude, then clothed, in order to understand the body’s essential structure, landscape training followed the same principle: in his influential treatise on landscape, Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes (1750–1819) wrote, “To understand the form of a tree and its branches, you must draw it in winter, when it has lost its leaves; then its skeleton can be understood as well as its entire structure.”[8] In the context of nineteenth-century landscape painting, then, the image of a tree standing alone has cultural ramifications far beyond its horticultural dimension, and can even be said to carry the aura of the individualized hero of history painting.

It is no accident that the two celebrated tree portraits of the period, the Bodmer Oak and Le Rageur, besides representing oaks, were both painted in the Forest of Fontainebleau. As landscape painting grew in importance, the Forest of Fontainebleau, about forty miles south of Paris, became a favored destination for artists throughout the Romantic era and into the early years of Impressionism.[9] In 1845, Rodolphe Töpffer (1799–1846), a prolific writer as well as the inventor of the modern comic strip, described its attraction thus: “the Forest of Fontainebleau is the first stop for the landscape painter, when, plagued by the necessity of escaping the endless repetition of academic models, he hoists his belongings onto his shoulders and sets off on his travels to find the picturesque. . . . Finally, he is home! The Forest of Fontainebleau is, so to speak, his own domain.”[10] Originally the hunting reserve of the kings of France, the forest had been nationalized during the Revolution of 1789 and eventually became a favored tourist destination. Artists began visiting the forest in the 1820s, settling in the neighboring village of Barbizon and producing countless depictions of the forest.

The forest’s renown owes much to the work of Claude-François Denecourt (1788–1875), a retired soldier and civil servant who, beginning in 1839, published numerous guides to the forest, laying out scenic routes and bestowing names on the forest’s most impressive trees.[11] His favored names were those of kings and emperors, and the recipients of these honors were, of course, oaks: Charlemagne, Clovis, Henri IV, Napoleon I; he even marked their sites with placards in the forest. Denecourt did not, however, name the tree traditionally known as Le Rageur, or, sometimes L’Orageux (The Stormy One), which is unique in that it signified an emotional but not a historical figure. The fact that so many artists of the Romantic period depicted this one tree, while the subsequent generation ignored it is, in itself, interesting, but it leads to the question of why this tree, since there were literally dozens of named trees in the forest. What set this tree apart? Why did it serve not only as visual inspiration but literary and political as well?

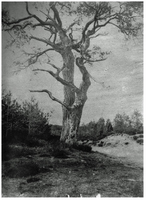

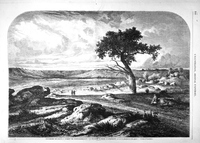

Le Rageur was located on the route Marie-Thérèse at the entrance to the Gorges d’Apremont, an area that until the mid-nineteenth century was a barren, rocky region; its inhospitable environment is seen in the painting of Corot in figure 1. Perhaps as a result of its desolate location, Denecourt omitted Le Rageur from most of his forest guides, although occasionally he did acknowledge its existence, as in his 1843 map, where the number ten marks the tree he identifies as L’Orageux (fig. 4).[12] The proximity of Le Rageur and Barbizon (spelled Barbison on older maps) can be seen in figure 4, where both sites are circled in red. In his tourist guides, Denecourt divided the forest into several picturesque itineraries for tourists, routes that included his favored trees named after rulers such as Charlemagne and Clovis. Le Rageur, however, as well as its bleak surroundings in the Gorges d’Apremont were always excluded. Despite this, the tree was hardly unknown. In his article of 1845 for L’Illustration, Töpffer described it thus: “at the entrance to a barren gorge, an isolated oak with an angry look, its tortured branches twisted back on itself, has the characteristic name that the locals altered for more assonance; for some it’s l’Orageux, for others, it’s le Rageur.”[13]

The tree’s striking appearance as well as its location, away from the popular tourist sites but close to the village of Barbizon, no doubt enhanced its attraction to artists, as they didn’t have a long trek to their subject and their work would be uninterrupted by day-trippers. Corot might well have been the earliest to depict Le Rageur, at least by that name. He painted the tree around 1830 (see fig. 1), depicting it from below, with its characteristic double trunk and branches leaning to the left and straining against the sky; it was a view that would become iconic. Corot valued his painting so highly that in 1867 he presented it as a gift to Charles de Tournemine, curator of the Musée du Luxembourg; it remained well-known throughout the century, even sold as a reproductive print.[14] Corot remained so fond of this tree that he reused it in subsequent paintings, including his View in the Forest of Fontainebleau of 1830–32 (Musée d’Art et Archéologie, Senlis) and his Flight into Egypt of 1839 (Musée de l’Hôtel-Dieu, Mantes-la-Jolie).

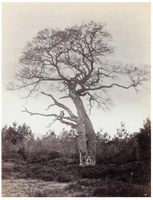

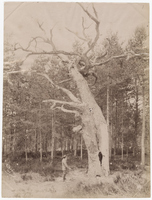

The accuracy of Corot’s depiction can be verified through comparison with the work of several contemporaneous photographers. Gustave Le Gray (1820–84) produced Fontainebleau, the Painter under Le Rageur (Fontainebleau, le peintre sous le Rageur) around 1849 (fig. 5); Eugène Cuvelier (1837–1900) produced [Le Rageur] Oak near a Path, Forest of Fontainebleau (Seine-et-Marne) ([Le Rageur] Chêne près d’un chemin, forêt de Fontainebleau [Seine-et-Marne]) in the 1860s (fig. 6); and Constant-Alexandre Famin (1827–88) produced Forest of Fontainebleau: Le Rageur (Forêt de Fontainebleau: Le Rageur) in about 1870 (fig. 7). In the two later photographs we can see the beginnings of the pine plantations that eventually overwhelmed the site. Fast-growing, commercially valuable trees, pines lacked the cultural resonance of the stately oak, and planting them throughout the forest in the 1830s and 1840s became especially contentious.[15]

Rousseau, much younger than Corot, campaigned vociferously against the pines, considering them an offense against nature and tradition.[16] The planting of pines in the forest was so controversial that, in 1852, Rousseau sent a petition (unsuccessful) to Napoleon III specifically requesting their removal and specifying the Gorges d’Apremont as one of the afflicted areas where these newly planted trees were destroying what he called “the old Gaullist character” of the forest.[17] As the century progressed, it became increasingly clear that Le Rageur symbolized this old Gaullist character.

The Musée du Louvre owns Rousseau’s watercolor Le Rageur: Old Oak in the Heath of the Gorges d’Apremont (Le Rageur: Vieux chêne sur les bruyères des gorges d’Apremont) (fig. 8), probably from the 1840s and inscribed on the back with the words “avant le semi des pins” (before the pines were planted). In this work, Rousseau viewed the tree from an angle different from Corot; he added the watercolor later, in the 1860s.[18] He returned to the image in Le Rageur: Old Oak in the Gorges d’Apremont (Le Rageur: Vieux chêne dans les gorges d’Apremont) (fig. 9), now in a private collection but widely known at the time: it was in his posthumous sale of 1868 and was bought by his fellow Barbizon artist Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña (1807–76), reappearing in the Edinburgh International Exhibition of 1886.[19] In 1892, a man writing under the name “Max. B.” published a personal memoir of Le Rageur, noting that “after the death of Rousseau, just before the war of 1870, knowing that Rousseau’s painting, Le Rageur, had just been sold for 35,000 francs, I went one morning to revisit the model. A woodsman, perhaps the brother of Rousseau’s peasant, added: ‘Hah! if you chopped down this tree, you wouldn’t get more than 15 francs for it.’ This man, lacking any artistic sensibility, and ignorant in his rustic naiveté, thus gave involuntary homage to Rousseau’s talent.”[20]

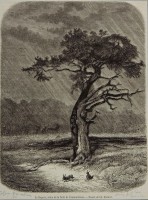

Rousseau was not alone in his campaign against the pines: in 1858, L’Illustration published a full-page wood engraving after a drawing by Diaz de la Peña’s student Auguste Anastasi (1820–89) titled Environs of Paris – Forest of Fontainebleau: Le Rageur, Gorges d’Apremont (before the Pines Were Planted) (Environs de Paris–Forêt de Fontainebleau: Le Rageur, Gorges d’Apremont [avant la plantation des pins]) (fig. 10). Clearly, these artists identified with the solitary Le Rageur as a metaphor for their protest against the increasing commercialism that valued the upstart pine plantations over the traditional oaks.

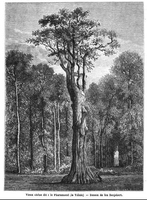

Among the numerous artists who depicted the tree, two others stand out. Antoine-Louis Barye (1795–1875), is better known today as an animalier, a sculptor of animals, but he was also a painter who lived and worked in Barbizon; Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863) called him a “sculpteur paysagiste” (sculptor landscapist).[21] Barye’s painting Le Rageur is undated, but it appeared in his memorial exhibition of 1875, and the pine growth would confirm a date sometime after mid-century (fig. 11).[22] Even Bodmer depicted Le Rageur, Tree in the Forest of Fontainebleau (Le Rageur, arbre de la forêt de Fontainebleau), for an article on the forest that appeared in Le magasin pittoresque in 1863 (fig. 12).[23]

It is difficult to ascertain the scope of Le Rageur’s influence because landscape paintings were often undated, and if exhibited often carried generic titles, so the identification of specific sites has presented difficulties for subsequent collectors, curators, and art historians. Exhibition and sales records list works by numerous artists that can no longer be located, most likely because they are now catalogued under alternate titles. In 1903, The Art Journal (London) carried a report stating: “The spring exhibitions at the Haymarket galleries of Messrs. Tooth and Messrs. McLean were of more than ordinary interest. At Messrs. [sic] Tooth’s the prominent pictures included Diaz’s magnificently realised ‘Le Rageur,’ a great oak in Fontainebleau Forest, painted in 1862.”[24] The catalogue raisonné for Diaz de la Peña lists as unknown the whereabouts of this painting, but lists another, showing Le Rageur older and already in decline, as Le Rageur, Stormy Weather (Le Rageur, temps d’orage), in the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen (fig. 13). There it is currently catalogued as Stormy Weather (Humeur de tempête), although it entered the collection as Impression of a Storm (Effet d’orage).[25] Diaz seemed especially fond of Le Rageur, depicting it in numerous paintings: the National Gallery in London owns The Storm of 1871, and the Norton Simon Museum has The Approaching Storm of 1870. A watercolor by Diaz de la Peña in the Morgan Library and Museum in New York certainly pictures Le Rageur but is catalogued as A Path Leading through Rocks and Trees under a Brooding Sky (fig. 14). The conflation of the names Rageur, Orage, and Orageux persisted even among contemporaries: in a guide of 1867, Fontainebleau: Son palais, ses jardins, sa forêt et ses environs (Fontainebleau: Its palace, its gardens, its forest and its environs), Adolphe Joanne described the tree as “an old oak with tormented branches, known by the name Le Rageur or L’Orageux.”[26] This has probably resulted in numerous depictions of Le Rageur being given cognate titles. As an example, the Harvard Art Museums’ wood engraving by Bodmer (see fig. 12) is catalogued in that collection as The Ill-Tempered, Tree in the Forest of Fontainebleau, although its title, Le Rageur, arbre de la forêt de Fontainebleau, is clearly visible on the image. Another problem results from the paucity of records of Barbizon landscapes, many of which are unsigned and undated: a painting recently sold by the Paris gallery Brame & Lorenceau as Le Rageur by Jules Dupré (1811–89) from around 1840 (fig. 15) has no traceable provenance, but it is clearly a portrait of that tree.

While artists’ attitudes towards Le Rageur can, at best, be inferred from their works that depict the tree standing alone against the sky, writers were more forthright. In the course of the century, many cited Le Rageur in a variety of contexts, but the best-known quotation does not actually cite it by name, although it is the only named tree in the forest meeting that description. Gustave Flaubert (1821–80) in Sentimental Education (1869) wrote of the Forest of Fontainebleau: “There were gnarled oaks, enormous, convulsive, struggling out from the soil, grasping at each other and, unyielding on their trunk-like torsos, they threw up their naked arms in cries of despair and furious threats, like a group of Titans paralyzed in the midst of their rage.”[27] While there were other oaks in the forest that might have shared some of Le Rageur’s emotive characteristics, Flaubert’s description omits the singular quality of Le Rageur that was noted by so many others: that it stood alone in its rage. One observer described it as “all cracked, scraggy, twisted like a dying old athlete . . . his straining twisted branches like arms making desperate appeals.”[28] This quality, of courage in the face of adversity, was especially appealing to those on the left of the political spectrum. In 1847 the art critic Thoré, whose politics were so Republican that he had to flee France two years later, wrote an article entitled “Par monts et par bois: La Forêt de Fontainebleau” (Through mountains and woods: The Forest of Fontainebleau) for the liberal journal Le constitutionnel. In it he stipulated: “It is there that Le Rageur writhes, this vigorous and contorted little oak that so many landscapists have portrayed; nearby are other oaks, more resigned although from the same family and the same temperament.”[29] The Republican hero Camille Pelletan (1846–1915) described Le Rageur in his memoirs: “A famous tree near Barbizon was known as Le Rageur. It was an oak of fabulous old age, with a trunk hollowed out and half-naked that twisted and turned, as though in a fit of rage, its branches withered, virtually leafless, but on high a few clusters of leaves.”[30]

These descriptions underscore Virgil’s portrayal of Aeneas—his age, isolation, and courage in the face of adversity. These qualities appear in numerous literary references throughout the century, but are perhaps most overt in the article of 1863 on the Forest of Fontainebleau in Le magasin pittoresque that Bodmer illustrated (see fig. 12). Here the gendered nature of Romance languages, where the word “tree” is masculine, becomes relevant and so is thus translated: “Le Rageur is old and tormented: perhaps his lower branches have been condemned by lightning to sterility, but, just as in a burning palace where the inhabitants take refuge in the tower, on high the sap still nourishes a lovely foliage. Le Rageur loves storms and rain; he braves these age-old enemies and spreads against the wind his naked arms, always poised for resistance.”[31] The author’s allusions then change from Virgil to La Fontaine, whose fables were gospel throughout France, and to emphasize his point, he offsets his quotation:

The timid stags flee in the mist, and, at the sound of thunder,

“We see fleeing the entire nation

Of rabbits who, over the heath,

Their eyes darting, ears alert,

Were feasting, and thyme was perfuming their banquet.”

And yet two hesitate to regain their “ruling sanctuary.” Only Le Rageur stands immobile, listening, shuddering, at the approaching thunder.[32]

The quotation within the quotation is taken from La Fontaine’s “Les Lapins” (The Rabbits), here interpreted as a contrast between the bravery of Le Rageur and the cowardice of the rabbits (although Bodmer expanded the cast to include two brave bunnies).[33] The alteration of the cited text underscores its subtext of bravery and cowardice: La Fontaine actually began with “Je vois” (I see [the entire nation of rabbits]), but here the anonymous author changed “Je vois” to “On voit” (We see [the entire nation of rabbits]); the italicization of “On” underscores the significance of the spectacle. The frightened rabbits’ now-abandoned “souveraine cité” (ruling sanctuary) has replaced La Fontaine’s far more plausible “souterraine cité” (underground sanctuary). The veiled challenge to authority implicit in all the images of Le Rageur and implied by Thoré and Pelletan is here made explicit, as was appropriate in a century marked by repeated revolutions and the constant censorship that would make such allusive language imperative.

Le Rageur even appeared in 1875 as an illustration in a children’s book, Les Petits Robinsons de Fontainebleau (The little Robinsons of Fontainebleau) by Pierre-Jules Hetzel (1814–86), the esteemed Republican publisher of Honoré de Balzac (1799–1850), Hugo, and Émile Zola (1940–1902).[34] Hetzel wrote it under his pseudonym P. J. Stahl, and, as he explained in his preface, he included illustrations in order “to have pass before the eyes of our readers the most remarkable sites of this famous forest.”[35] Of the twenty-two illustrations depicting these remarkable sites, Hetzel included only one named tree, an image of Le Rageur by Fortuné-Louis Méaulle (1844–1901) (fig. 16), based on the earlier photograph by Famin (see fig. 7).[36] Here the angry, brooding tree protects the children, “the little Robinsons,” from an impending storm:

But the storm had grown so violent and the wind blew with such fury that they couldn’t breathe. They were forced to take shelter under a tree whose name would have astonished them had they known it. It was called Le Rageur, a name that went well with the weather they were having. In that moment, silhouetted by the lightning bolts that zig-zagged across its branches, Le Rageur merited its name. Its naturally twisting branches were convulsed by the blasts of wind.[37]

The fame of Le Rageur was not limited to France. In the 1872 British novel Bessie by Julia Kavanagh (1824–77), there is a scene in the Forest of Fontainebleau where a character asks “‘What tree is that, Bessie? — the Roger?’ ‘Rageur,’ I corrected; ‘it is a very distorted tree, and looks angry, and so it has been called the Rageur.’”[38] Harry Meltzer’s article “Fontainebleau” of 1879 in the Chicago Daily Tribune described the Gorges d’Apremont, although probably from an earlier visit as there is no mention of the pines. For him it was “a vast plain, carpeted with heath and bracken, dotted with mighty boulders of every conceivable shape, between which rise great oaks, whose far-spreading branches have braved the storms and showers of thrice a hundred years. Many are but shells. The stem and branches make a goodly show, but the heart is withered. One seared and blighted veteran flings its arms abroad like an enormous cuttle-fish, or a disheveled fury. They have named it the ‘Rageur.’”[39]

Le Rageur Grows Old

Even as the fame of Le Rageur was spreading internationally, the tree was aging, its vigor declining. In France it increasingly evoked sentiments of sadness, mourning, and despair. The tree had “braved the storms,” as numerous writers noted, and the century’s turbulent history gives ample evidence of those storms. The oblique nature of the literary descriptions made them all the more powerful, evocative across classes and politics of the period. And perhaps that was, in part, the source of Le Rageur’s persistence as a trope. Anger and despair, courage and isolation, figure across the entire spectrum of literary references. In the novel Manette Salomon of 1868 by Edmond de Goncourt (1822–96) and Jules de Goncourt (1830–70), Le Rageur echoes the melancholy of the artist Coriolis—as well as the description Flaubert had published the previous year:

The rocky landscapes now appeared to him with brute endurance and naked strength. Even the magnificent vegetation, the enormous trees, the superb oaks, no longer gave him that happy sensation of the goodness of life that we feel before the graceful and welcome buds that burst forth gracefully and sweep upwards with no effort. Instead, their black branches twist upward against the sky, and the convulsion of their strength, the despair of their limbs, the torment that disfigures them from top to bottom, their expression of titanic anger, has given one of these furious giants of the woods the name that they all deserve: Le Rageur.[40]

The novelist Victor Cherbuliez (1829–99) is virtually forgotten today, but he was much admired in his day as an esteemed member of the Académie Française. His novel of 1880, Amours fragiles (Fragile loves), was even partially published in the respected Revue des deux mondes.[41] Le Rageur became for Cherbuliez a harbinger of death, of time passing:

He pointed out on the side of the road the one called Le Rageur, and, as everyone knows, Le Rageur is a giant oak which, truth be told, no longer exists; he has laid down his arms; he is gone. Farewell buds and acorns! All that remains is a broken trunk, boughs without branches, covered with cuts and scars; who can count his wounds? In vain, did the last few Springtides sing to him their sweetest songs, they will nevermore awaken him, nothing stirs in his old heart and his exhausted sap. He has no more leaves and the birds avoid him. For so long he battled against the winds, against the harsh winters, against fate. He has fallen into eternal sleep and his ravaged appearance betrays astonishment at his demise. But this vanquished one is the walking dead, he is still firm on his feet, his supreme defeat is like a victory.[42]

By this time, the younger generation of landscape artists had abandoned both the Forest of Fontainebleau and Le Rageur, choosing, instead, sunnier climes and happier motifs. In the final decades of the century, the fate of Le Rageur rapidly descended from tragedy to farce. A revue called Le jardin de Diane [The Garden of Diane], performed in Fontainebleau at the salon of the Duchess of Bellune in 1885, brought the period to a close.[43] It made explicit the reading of Le Rageur as radical politics, the sworn enemy of entrenched power, while at the same time signaling that that era was definitively passé.

Le jardin de Diane included as characters several of Denecourt’s titled oaks in the Forest of Fontainebleau: Henry IV, François Ier, and even Le Pharamond, named after the first king of France but, very much like Bodmer’s oak, notable for its reserve and lack of emotional affect (fig. 17). In the revue, Le Rageur is joined by a wholly fictitious tree character, L’Enragé, the epithet for ultraleft partisans since the Revolution of 1789. François Ier asks Le Rageur: “Doesn’t it exhaust you to contort your arms like that?” Le Rageur responds, “You know . . . it’s my habit.” When Henri IV asks L’Enragé why he is doing the same thing, he responds “To be like him,” to which François Ier responds “What an old copycat!”[44] The contrast of monarchy and revolution here is clear—as is the sentiment that all this emotional posturing is now very much out of date.

The image of Le Rageur as an aging warrior, in decline but still formidable, that infused later mentions of the tree, might well apply to the artists of Barbizon, who were then also in their final years. By the 1870s, the young Impressionists had succeeded the Barbizon artists as the radical generation, and these later landscape artists chose as subjects different venues, different trees. After the Franco-Prussian War and the Commune of 1871, the age of revolutions in France was over, and with it Le Rageur as a symbol of the courageous, solitary battle against superior forces. So, when Georges Lafosse (1844–80) drew the tree for Le journal amusant in 1875, his caricature was captioned, albeit prematurely: “Here is Le Rageur, one of the trees most studied by artists. Unfortunately, dead” (fig. 18). And that was how Auguste-Louis Lepère (1849–1919) portrayed the tree in his wood engraving of 1887 for a feature on the Forest of Fontainebleau in La revue illustrée, later republished in his portfolio La forêt de Fontainebleau of 1908 (fig. 19).[45] By the late 1880s, Denecourt’s Fontainebleau guidebook series, now taken over by Charles Colinet, described Le Rageur as “an old ruin of an oak.”[46] By the 1890s, the end was clearly near.[47] But still Le Rageur exerted its spell over its century. Bodmer, a gifted photographer as well as a painter, returned to immortalize its last gasp (fig. 20), and, as a fitting twentieth-century post mortem, Le Rageur was commemorated on postcards (fig. 21). By the end of the nineteenth century, the gnarled and twisted Le Rageur, as well as the Romantic movement it exemplified, had receded into the past. Other artists and other trees now expressed the soul of the nation: Monet’s decorative poplars, Paul Cézanne’s (1839–1906) geometric pines.

In 1904 Le Rageur finally collapsed. An obituary, “Le Rageur de Fontainebleau,” appeared in the Paris periodical Le monde pittoresque in the column Ce Qui Disparaît (Those Who Have Passed Away). It read, in part: “Ramblers know well this old oak, so often struck by lightning, that sprawled at the entrance to the Gorges d’Apremont. Its gnarled branches, violently twisting, angry, so to speak, earned it the name of ‘Le Rageur.’ The Easter rains got the better of this ancient forebearer, whose roots were laid bare. It could not regain enough support in the watery soil to protect it against the violence of the mid-April winds: all at once ‘Le Rageur’ collapsed.”[48] A long and more emotive memoir appeared in L’abeille de Fontainebleau: “Before it became surrounded by pine trees, its silhouette stood out from the sand and rocks. Often struck by lightning but unwilling to either bend or break, it remained upright, invincible, invulnerable, fantastic and twisting in the sky its superb branches.”[49]

After its demise, Le Rageur slowly faded from memory, but for most of the nineteenth century the tree had summoned up feelings of high emotion, of resistance and strength. For Republicans like Thoré it was an emblem of their own political struggle against superior forces; for artists it was, perhaps, a reflection of their condition in society, clinging to their principles, isolated but courageous. Angry, alone, battling against all odds, but brave, steadfast and fearless, these qualities were evoked time and again in descriptions of Le Rageur, an appropriate tree for a turbulent century. Its complex history was intertwined, indeed “wrapped,” with that of Barbizon, the Forest of Fontainebleau, Romanticism, and nineteenth-century France. And so, it is only fitting that when Pablo Picasso (1881–1973) moved to Fontainebleau in 1921, where, in the course of the summer, he produced his masterpieces Three Women at the Spring (Museum of Modern Art, New York) and Three Musicians (Museum of Modern Art, New York), one of his first works was a pastel invoking Corot’s Le Rageur and the rich, layered tradition of the Forest of Fontainebleau, and of nineteenth-century France, that the tree represented (fig. 22).[50]

Acknowledgments

Scholarship is a collaborative effort, and so I thank my many friends and colleagues who contributed to this article: especially Georgia Barnhill, Jane Becker, Aimée Boutin, Silvie Brame, Stephen Edidin, Madeleine Fidell-Beaufort, Jeffrey Hall, Christian Huemer, Herman Lebovics, Asher Miller, Laura Nørholt, Simon Kelly, Alexandra Morrison, Miquel Rolande, Alan Wallach, and Sally Webster; an especially warm thank-you to the two anonymous NCAW readers for their valuable suggestions. I also thank Gérard Bayle-Labouré, whose splendid website, En Forêt de Fontainebleau, hier et aujourdhui, has collated valuable information and images of the forest: https://foret-fontainebleau.teria.fr/.

Notes

All translations are by the author unless otherwise noted.

[1] “Arbres de la forêt, vous connaissez mon âme!” Victor Hugo, “Aux arbres,” June 1843, in Les contemplations, ed. Léon Cellier (1856; repr., Paris: Garnier Frères, 1969), 181–82, no. 24.

[2] The Monet painting was long called The Chailly Road; Douglas Cooper retitled it The Bodmer Oak in his article “The Monets in the Metropolitan Museum,” The Metropolitan Museum Journal, no. 3 (1970): 281–305.

[3] Frederic Jameson, Postmodernism, or, The Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1991), 100–3.

[4] For a brief overview of the symbolism of trees, see Annette Giesecke, The Mythology of Plants: Botanical Lore from Ancient Greece and Rome (Los Angeles: J. Paul Getty Museum, 2014).

[5] Virgil, The Aeneid of Virgil, book 4, trans. Allen Mandelbaum (New York: Bantam, 1961), 602–15.

[6] “l’arbre sacré, représentant la force, et la persistance, l’arbre national qui servait de cathédrale naturelle à nos ancêtres pour la célébration des mystères religieux.” Théophile Thoré, “Par monts et par bois: La Forêt de Fontainebleau I,” Le constitutionnel, November 27, 1847, 1.

[7] I discuss landscape pedagogy extensively in my article “Learning to Draw Landscape in Nineteenth-Century France,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 21, no. 2 (Summer 2022), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2022.21.2.2.

[8] “Pour bien connoître la forme d’un arbre de ses branches, il faut le dessiner pendant l’hiver, lorsqu’il est dépouillé de ses feuilles; on en saisit alors la structure, et l’on se rend compte de toute sa charpente.” Pierre-Henri de Valenciennes, Elemens de perspective pratique à l’usage des artistes, suivis de réflexions et conseils à un élève sur la peinture et particulièrement sur le genre du paysage (Paris: l’auteur, Desenne, Duprat, an 8 [1799]), 226. Available from: https://gallica.bnf.fr/.

[9] For an overview of the importance of the Forest of Fontainebleau to art history, see Nicolas Green, The Spectacle of Nature: Landscape and Bourgeois Culture in Nineteenth-Century France (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 1990); Greg M. Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000); and Kimberly Jones et al., In the Forest of Fontainebleau: Painters and Photographers from Corot to Monet, exh. cat. (Washington, DC: National Gallery of Art, 2008). The exhibition catalogue L’école de Barbizon: Peindre en plein air avant l’impressionisme, ed. Vincent Pomarède, exh. cat. (Lyon: Musée des Beaux-Arts; Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002) provides a compendium of images.

[10] “la forêt de Fontainebleau est-elle la première étape du peintre paysagiste, lorsque, tourmenté du besoin de se soustraire à l’éternelle répétition du platane académique, il charge son bagage sur ses épaules et se met en route pour son voyage à la recherche du pittoresque. . . . D’ailleurs, il est là chez lui. La forêt de Fontainebleau est en quelque sorte son domaine.” R. Töpffer, “Résidences royales. Fontainebleau. La forêt,” L’Illustration, November 8, 1845, 152.

[11] His first guidebook was Claude-François Denecourt, Guide du voyageur dans la forêt de Fontainebleau (Fontainebleau: chez l’auteur, 1839). For a summary of Denecourt’s career, see Kimberly Jones, “Landscapes, Legends, Souvenirs, Fantasies: The Forest of Fontainebleau in the Nineteenth Century,’’ in Jones et al., In the Forest of Fontainebleau, 14–16. See also “Les guides Denecourt,” Archives Départementales de Seine-et-Marne, May 8, 2020, https://archives.seine-et-marne.fr/.

[12] Claude-François Denecourt, Carte du voyageur à Fontainebleau, dressée à l’aide des meilleurs plans, augmentée de tous les nouveaux percements et rectiffiée [sic] sur le terrain par F. Denecourt (Fontainebleau: Denecourt, Thierry Frères, 1843). In 1860, after long omitting it, Denecourt added Le Rageur to his extensive list of forest trees. Claude-François Denecourt, La forêt de Fontainebleau, ses beautés pittoresques, itinéraire de ses plus jolies promenades, aperçu des travaux Denecourt, 17th ed. (Paris: Dentu, 1860), 13.

[13] “à l’entrée d’une gorge aride, un autre chêne isolé, à la mine renfrognée, aux branches contournées sur elles-mêmes, a reçu un nom caractéristique, que les gens du pays ont altéré à cause de l’assonance; pour les uns c’est l’Orageux, pour les autres, c’est le Rageur.” Töpffer, “Résidences royales,” 152.

[14] The provenance of Corot’s Le Rageur is detailed in Corot, 1796–1875, exh. cat. (Paris: Réunion des Musées Nationaux, 1996), 134, cat. 33. The reproductive print is listed in Adolphe Braun, Catalogue général des reproductions inaltérables au charbon d’après les originaux peintures, fresques et dessins des musées d’Europe, des galeries et collections particulières les plus remarquables et des œuvres contemporaines (Paris, Alsace, New York: Maison Ad. Braun, 1896), 151, no. 14.724: Corot, Le Rageur dans la plaine, à Fontainebleau, fr. 7.50.

[15] Jules Clavé dated the widespread plantation of pines in the forest to about 1833. Jules Clavé, “Études forestiéres: La forêt de Fontainebleau,” Revue des deux mondes, May 1, 1863, 154.

[16] Rousseau’s antipathy toward the pine plantation is discussed extensively by Green, The Spectacle of Nature; Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France; and Jones et al., In the Forest of Fontainebleau.

[17] For Rousseau’s petition, along with an English translation, see Appendix B, “Petition to Napoleon III [1852],” in Thomas, Art and Ecology in Nineteenth-Century France, 214–17.

[18] See Catalogue de la vente qui aura lieu par suite du décès de Théodore Rousseau, Hôtel Drouot (Paris: J. Claye, 1868), no. 137: Le Rageur. Vieux chêne sur les bruyères des gorges d’Apremont. Ancien dessin repris à l’aquarelle en 1865. See also “Le Rageur. Vieux chêne sur les bruyères des gorges d’Apremont,” Collections, Louvre, last updated June 21, 2024, https://collections.louvre.fr/.

[19] See Catalogue de la vente qui aura lieu par suite du décès de Théodore Rousseau, no. 20: Le Rageur. Vieux chêne dans les gorges d’Apremont. On the 1886 Edinburgh exhibition, see “French Pictures in Edinburgh,” Saturday Review of Politics, Literature, Science and Art, May 1, 1886, 603. The work is also cited as being in the London International Exhibition of 1904 in C. J. H., “The Constantine Ionides Bequest. Article III—The French Landscape Painters,” Burlington Magazine 6, no. 19 (October 1904): 26. Despite this, Ionides’s painting by Rousseau that is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum is definitely not Le Rageur.

[20] “Après la mort de Rousseau, peu de temps avant la guerre de 1870, sachant que le tableau de Rousseau, le Rageur, venait d’être vendu 35,000 fr., j’allai un matin revoir le modèle. Un bûcheron, peut-être le frère du paysan de Rousseau, ajouta: ‘Eh! bien, si on débitait cet arbre, on n’en ferait pas plus de 15 fr.’ Cet homme dépourvu de tout sens artistique, dans sa rustique naïveté, rendait par là, sans le savoir, un hommage involontaire au talent de Rousseau.” Max. B., “Bibliographie. L’Art et la nature, par Victor Cherbuliez, de l’Académie française,” L’abeille de Fontainebleau, April 22, 1892, n.p.

[21] Eugène Delacroix to Jean-Baptiste Pierret, October 1828, in Lettres de Eugène Delacroix (1815 à 1863), ed. Philippe Burty (Paris: A. Quantin, 1878), 95.

[22] Catalogue des œuvres de Antoine-Louis Barye, exposé à l’École des Beaux-Arts (Paris: J. Claye, 1875), no. 383: Forêt de Fontainebleau, Le Rageur.

[23] “La Forêt de Fontainebleau,” Le magasin pittoresque, May 1863, 153. The Harvard Art Museums, which holds a copy of Bodmer’s engraving (R14928), lists Cosson as the wood engraver, although the work is unsigned.

[24] Frank Rinder, “Round the London Galleries,” The Art Journal, May 1903, 158.

[25] See Pierre Miquel, Narcisse Diaz de la Peña (1807–1876), vol. 2, Catalogue de l’œuvre peint (Courbevoie/Paris: ACR, 2006), cat. nos. 1201, 1563. Catalogue no. 1563 entered the collection of the Statens Museum for Kunst, Copenhagen, in 1976 as part of the Herbert Melbye collection and is catalogued as KMShm2.

[26] “un vieux chêne aux branches tourmentées, désigné sous le nom du Rageur ou de l’Orageux.” Adolphe Joanne, Fontainebleau, son palais, ses jardins, sa forêt et ses environs (Paris: L. Hachette, 1867), 178.

[27] “Il y avait des chênes rugueux, énormes, qui se convulsaient, s’étiraient du sol, s’étreignaient les uns les autres, et, fermes sur leurs troncs, pareils à des torses, se lançaient avec leurs bras nus des appels de désespoir, des menaces furibondes, comme un groupe de Titans immobilisés dans leur colère.” Gustave Flaubert, L’éducation sentimentale: Histoire d’un jeune homme (1869; repr. Paris: Garnier-Flammarion, 1969), 347.

[28] “Tout crevassé, rabougri, tordu comme un vieil athlète mourant, il semblait de ses branches allongées et tendues faire des appels de bras désespérés.” Max. B., “Bibliographie,” n.p.

[29] “C’est là que se tortille le rageur, ce petit chêne nerveux et convulsif dont tant de paysagistes ont fait le portrait; et, près de lui, quelques autres chênes plus résignés, quoique de la même famille et du même tempérament.” Thoré, “Par monts et par bois,” 1.

[30] “Un arbre, tout près de Barbizon, était fameux sous le nom du Rageur. C’était un chêne, d’une vieillesse fabuleuse, au tronc creusé et à moitié dénudé, qui crispait et tordait, comme dans un accès de fureur, ses branches desséchées, à peine garnies, de loin en loin, de quelques houppes de feuilles.” Camille Pelletan, “Une éducation républicaine,” unpublished manuscript, quoted in Jean Pinon, “Les chênes vus par les peintres,” Revue forestière française 71, no. 1 (2019): 78.

[31] “Le Rageur est vieux et tourmenté; peut-être ses rameaux inférieurs ont-ils été condamnés par la foudre à la stérilité: la sève, se retirant vers la cime, comme dans un palais incendié les habitants se réfugient au faîte, nourrit encore un beau feuillage; le Rageur aime l’orage et la pluie; il brave ces ennemis séculaires et déploie contre le vent ses bras dépouillés toujours disposés à la résistance.” “La forêt de Fontainebleau,” 154.

[32] “Les cerfs timides s’élancent dans la vapeur, et, au bruit de la foudre, / On voit fuir aussitôt toute la nation / Des lapins qui, sur la bruyère, / L’oeil éveillé, l’oreille au guet, / S’égayaient, et de thym parfumaient leur banquet. / Il y en a deux encore qui hésitent à regagner ‘leur souveraine cité.’ Seul, le Rageur immobile écoute en frémissant le tonnerre qui s’approche.” “La Forêt de Fontainebleau,” 154, emphasis in original.

[33] Jean de La Fontaine, “Les lapins,” in Fables de La Fontaine, book 10 (1678; repr. Paris: Garnier, 1855), fable 15.

[34] P. J. Stahl [Pierre-Jules Hetzel], Les Petits Robinsons de Fontainebleau (Paris: J. Hetzel, 1878).

[35] “pour faire passer sous les yeux de nos lecteurs les points les plus remarquables de la célèbre forêt.” Stahl, “Avertissement,” Les Petits Robinsons, n.p.

[36] Stahl, Les Petits Robinsons, n.p. (Méaulle’s image appears in chap. 15). Méaulle reused his image of Le Rageur in his own illustrated novel, Et moi aussi, je suis peintre! (Paris: Librairie d’Éducation Nationale, 1904).

[37] “Mais l’orage était devenu si violent et le vent soufflait avec tant de fureur, qu’il leur coupait la respiration. Ils furent obligés de prendre un point d’appui contre un arbre dont le nom les aurait bien étonnés s’ils l’avaient connu. Il s’appelait le Rageur, un nom qui allait bien avec le temps qu’il faisait. Pour le moment, sillonné par les éclairs qui traversaient ses branches en zigzag, le Rageur méritait son nom. Ses branches naturellement contournées se crispaient sous l’action des vents.” Stahl, Les Petits Robinsons, n.p. (the quotation appears in chap. 15).

[38] Julie Kavanagh, Bessie, vol. 2 (London: Hurst and Blackett, 1872), 277.

[39] Harry Meltzer, “Fontainebleau,” Chicago Daily Tribune, August 3, 1879, 11.

[40] “Les paysages de rochers lui apparaissaient maintenant avec leur dureté rude, et leur rigueur nue. Même les magnificences de la végétation, les arbres énormes, les chênes superbes ne lui donnaient point cette heureuse impression du bonheur des choses qu’on ressent devant l’épanouissement facile et béni de ce qui jaillit sans effort, et de ce qui monte au ciel sans souffrir. A voir la torsion de leurs branches noires sur le ciel, la convulsion de leurs forces, le désespoir de leurs bras, le tourment qui les sillonne du haut en bas, l’air de colère titanesque qui a fait donner à l’un de ces géants furieux du bois le nom qu’ils méritent tous: le Rageur.” Edmond de Goncourt and Jules de Goncourt, Manette Salomon, vol. 2, section 96 (Paris: Librairie Internationale, 1868), 101. See note 27 on Flaubert.

[41] See Victor Cherbuliez, “Les inconséquences de M. Drommel,” Revue des deux mondes, December 15, 1879, 804–57.

[42] “Il lui montrait du doigt, au bord de la route, celui qu’on a appelé le Rageur, et comme chacun sait, le Rageur est un gros chêne qui, à vrai dire, n’est plus; il a rendu les armes, il est fini. Adieu les bourgeons et les glands! il ne lui reste qu’un tronc crevassé, des branches sans rameaux, couvertes de balafres et de cicatrices; qui pourrait compter ses blessures? En vain les derniers printemps lui ont chanté leurs plus douces chansons, ils n’ont pu le réveiller, rien n’a remué dans son vieux coeur et dans sa sève tarie. Il n’a plus de feuilles, et les oiseaux l’évitent. Longtemps il a bataillé contre les vents, contre les noirs hivers, contre les destins; il s’est endormi à jamais dans sa lassitude, et il porte sur son front ravagé l’étonnement de sa fin. Mais ce vaincu est mort debout, il est encore solide sur ses pieds, sa suprême défaite ressemble à une victoire.” Victor Cherbuliez, Amours fragiles (Paris: Hachette, 1880), 320.

[43] See [Victor] Leduc, Fontainebleau: Le jardin de Diane, revue en deux actes et un prologue par M. Leduc avec une scène inédite de Gustave Nadaud (Fontainebleau: E. Bourges, 1885). Leduc was probably Victor-François-Marie Perrin, 3e duc de Bellune (1828–1907). On this performance, see Victor Du Bled, “La comédie de société. XIII. Suite et fin,” La revue hebdomadaire, 2nd ser., April 6, 1901, 39–42.

[44] “FRANÇOIS Ier, au Rageur. Ça ne vous fatigue pas de tortiller ainsi vos bras? LE RAGEUR. Vous savez . . . l’habitude. . . . HENRY IV, à l’Enragé. Et vous? L’ENRAGE. Pour faire comme l’autre. . . . FRANÇOIS Ier. Quel vieux singe!” Leduc, Fontainebleau, 35.

[45] Lepère’s wood engraving was first published as Le Rageur in Maurice Talmeyr, “La forêt de Fontainebleau, l’hiver II,” La revue illustrée, June 1, 1887, 390.

[46] “une vieille ruine de chêne, c’est le Rageur.” Charles Colinet, Indicateur de Fontainebleau: Palais, forêt, environs; 22e édition des guides Denecourt-Colinet (Fontainebleau: chez l’auteur, 1888), 148.

[47] “Tout crevassé, rabougri, tordu comme un vieil athlète mourant, il semblait de ses branches allongées et tendues faire des appels de bras désespérés.” Max. B., “Bibliographie,” n.p.

[48] “Les promeneurs connaissent bien ce vieux chêne, maintes fois foudroyé, qui allongeait à l’entrée des gorges d’Apremont ses branches noueuses, aux torsions violentes, hargneuses, pour ainsi dire, qui lui avaient valu ce nom de ‘Rageur.’ Les pluies de Pâques ont eu raison de l’ancêtre; les racines se sont déchaussées et n’ont pas trouvé dans la terre diluée un appui assez résistant contre la violence des vents de la mi-avril: ‘le Rageur’ s’est écroulé tout d’une pièce.” J. Bruyère, “Ce Qui Disparaît. Le Rageur de Fontainebleau,” Le monde pittoresque, May 15, 1904, 455.

[49] “Naguère, avant qu’il ne fût entouré de pins, il détachait sur les sables et sur les rochers sa silhouette tourmentée. Souvent foudroyé, mais ne sachant ni plier ni rompre, il était resté debout, invincible, invulnérable, fantastique, et tordant dans le ciel ses branches superbes.” “La fin du ‘Rageur,’” L’abeille de Fontainebleau, April 29, 1904, n.p.

[50] I thank Jeffrey Hall and Alexandra Morrison of the Museum of Modern Art, New York, for this identification. Picasso’s dealer at the time was his Paris neighbor Paul Rosenberg, who purchased the Corot painting shortly after Picasso returned from Fontainebleau. See the receipt for this acquisition, I.C.30.b, Paul Rosenberg Archives, Museum of Modern Art Archives, New York, NY.