The Origins of the Taste for Barbizon Painting in Britain: Paul Durand-Ruel’s Exhibitions of the Society of French Artists

by Simon Kelly and Andrew WatsonSimon Kelly is curator and head of the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Saint Louis Art Museum. He has published extensively on nineteenth-century French art, and particularly Barbizon painting, including the book Théodore Rousseau and the Rise of the Modern Art Market: An Avant-Garde Landscape Painter in Nineteenth-Century France (Bloomsbury, 2021). He has also organized many major exhibitions including Millet and Modern Art: From Van Gogh to Dalí (2020) and Matisse and the Sea (2024). He received his PhD from the University of Oxford, where he also taught art history. His research interests have focused on landscape painting, cultural markets, and the history of collecting. He is currently writing a book on the Barbizon painters.

Email the author: simon.kelly[at]slam.org

Andrew Watson, associate lecturer with the Open University, is a specialist in nineteenth-century art, with an emphasis on collecting. He has written extensively on British collectors of French painting, including a book on the remarkable Scottish collector James Duncan of Benmore (1834–1905) and articles for Journal of the Scottish Society for Art History, Cahiers Bruxellois: Revue d’histoire urbaine, Bulletin de la Société des amis du Musée national Eugène Delacroix, The Metropolitan Museum of Art Journal, and Burlington Magazine. In his most recent article (Burlington Magazine, May 2024) he definitively established the early history of Eugène Delacroix’s Death of Sardanapalus. Andrew has written seven entries for Charles Sebag Montefiore’s forthcoming (2027) Dictionary of British Art Collectors: 1600–1939, an online publication that will be hosted by the National Gallery, London.

Email the author: awartstudies1905[at]gmail.com

Citation: Simon Kelly and Andrew Watson, “The Origins of the Taste for Barbizon Painting in Britain: Paul Durand-Ruel’s Exhibitions of the Society of French Artists,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.3.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Scholarly Article|Appendix

On December 10, 1870, the French art dealer Paul Durand-Ruel (1831–1922) opened an exhibition of French painting in his new gallery in London at 168, New Bond Street. One hundred and eight paintings were on view in this First Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists, a society created by Durand-Ruel to promote the artists in his stock. The reviewer for the journal Art Pictorial and Industrial wrote: “There surely never was exhibited before a collection of French paintings of such marvelous excellence.”[1] At the center of the installation was a selection of Barbizon paintings, the first of many to be included in the eleven exhibitions of the Society of French Artists in London between 1870 and 1875. This article explores the impressive range of works in these exhibitions by the leading figures of the Barbizon School, notably Théodore Rousseau (1812–67), Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot (1796–1875), Jean-François Millet (1814–75), Jules Dupré (1811–89), Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña (1807–76), Charles François Daubigny (1817–78), and Constant Troyon (1810–65).[2] It argues that these displays served as a principal catalyst in the formation of a British taste for paintings of the Barbizon School, or the “School of 1830,” in the words of Durand-Ruel.[3] The evolution of this taste offers an important antecedent and parallel to Durand-Ruel’s subsequent and better-known promotion of Impressionist painting in Britain.

The eleven exhibitions of the Society of French Artists relate closely to the growing scholarly interest in the growth of transnational dealer networks across Europe in the mid-to-late nineteenth century.[4] The Paris-London axis played a central role in this growth. Anne Robbins has provided the most in-depth and comprehensive account of Durand-Ruel’s London gallery.[5] However, the individual exhibitions have not been explored in detail, and particularly the central role of Barbizon painters in them. The appendix to this article details the Barbizon pictures on view at the eleven exhibitions between 1870 and 1875. Over the run of the exhibitions, Corot showed 109 paintings, Millet 37, Rousseau 39, Dupré 82, Diaz de la Peña 23, Troyon 17, Daubigny 37, and Charles Émile Jacque (1813–94) 3. Numerically, between 1870 and 1871, the year that he himself was in London, Durand-Ruel exhibited the greatest number of Barbizon paintings, which accounted for almost 50 percent of works shown. As we shall see, although he showed fewer Barbizon works in the later exhibitions, he continued to display major pictures, particularly by Millet and Corot.

Background

In moving to London, Durand-Ruel was trying to break into an existing, if limited, market for Barbizon paintings. The dealer was aware of the pioneering London exhibition of Barbizon paintings organized by John Arrowsmith (1790–1849) in 1848, which it has been claimed gave rise to British enthusiasm for the Barbizon School.[6] A body of Barbizon work had also appeared at the retrospective exhibition of French paintings at Lichfield House in 1851 and at the International Exhibition of 1862.[7] Daubigny and Corot showed too at the Royal Academy exhibitions.[8] Perhaps most notably, Ernest Gambart’s (1814–1902) French gallery had regularly shown work by Barbizon painters since its inception in 1854.[9] Troyon, the best known and most successful Barbizon painter in London in 1850s, was especially close to Gambart, whom he visited in England in 1853 and again in 1857 on a trip to the Manchester International Exhibition.[10] Rousseau also showed work from 1854 until 1861 with the dealer. Corot exhibited two paintings in 1859. Other Barbizon pictures also appeared: two by Dupré in 1855; one by Millet in 1856; and one by Gustave Courbet (1819–77) and three landscapes by Daubigny in 1859.[11] For all his support of Barbizon painters, Gambart was more lukewarm in his support for the more experimental, avant-garde qualities of their work, especially their lack of finish. Gambart had indeed reserved his greatest enthusiasm for the highly finished paintings of other popular French painters in London, notably Jean Louis Ernest Meissonier (1815–91), Edouard Frère (1819–86) (with whom he maintained an exclusive contract), Jean Léon Gérôme (1824–1904), and Rosa Bonheur (1822–99), whose The Horse Fair (1852–55; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) he had bought for 40,000 francs in 1855.

From the 1850s onward, Agnew & Sons also dealt in Troyon’s pictures, which found favor with several of its English clients. In 1856, for example, Agnew sold Troyon’s The Water-Cart (location unknown) to the industrialist Edwin Bullock (1802–70), and in 1867, Landscape with Cattle (location unknown) to the banker James Price (1809–95).[12] In the 1850s and 1860s, Troyon was the only Barbizon artist listed in Agnew’s stock books. One English collector who made an important acquisition of Corot’s work was Lord Frederic Leighton (1830–96). In 1865 he purchased Corot’s The Four Times of the Day: Morning, Noon, Evening, Night (ca. 1858; National Gallery, London) from the writer and publisher Alfred Cadart (1828–75), whose business partner, Jules Luquet (b. 1824), had recently acquired the pictures at Gabriel Alexandre Decamps’s (1803–60) studio sale.[13] By 1866, these important panels were installed in the drawing room of Leighton’s London residence at 2, Holland Park.[14] Another Corot that entered an English collection in the 1860s was Landscape with Cattle (Bowes Museum, County Durham), which Josephine Bowes bought from the influential auctioneer Jules Auguste Boussaton (1821–1901) in 1868.[15] At some point before 1868, the poet and art collector Chauncey Hare Townshend (1798–1868) acquired Rousseau’s The Pond (1855; Victoria and Albert Museum, London), which formed part of his bequest to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1868.[16]

Despite these examples of existing support for Barbizon painting, Durand-Ruel undoubtedly recognized an opportunity to promote in London the full range of Barbizon work, in all its experimental quality. In the 1860s, he had already begun to exert his influence on the British market, supplying pictures by Daubigny, Diaz de la Peña, and Troyon to Agnew, Gambart, Thomas McLean (1845–94), and Henry Wallis (1830–1916).[17] However, his exhibition of 1870–71 represented a previously unrivaled display of Barbizon work in London, both in terms of the range and the size of the work on view, including grand decorative paintings, of the kind favored by Leighton, as well as smaller pieces. Durand-Ruel’s choice of works for his exhibition can indeed be seen as a conscious challenge to the leading roles of Gambart and Agnew in promoting and selling French paintings on the British art market. His exhibition represented a way of establishing his distinctive brand on the British art stage.

Durand-Ruel’s first show, in 1870–71, was overseen by the dealer himself, who had traveled to London from Paris on September 18, 1870, with his family, in order to escape the Franco-Prussian War.[18] There Durand-Ruel became part of a significant community of French expatriates who had also fled France. At his home in Brompton Crescent, just south of Knightsbridge, he, his wife, and his four children were neighbors to his friend and client, the opera singer, Jean-Baptiste Faure (1830–1914), whose collection Durand-Ruel had shipped over to London, together with that of the high-class Parisian tailor, Laurent-Richard (1811–86). As daybooks in the Durand-Ruel archive reveal, the dealer also shipped much of the contents of his gallery’s stock over with him. During the month of September 1870, for example, he shipped eighty-three paintings to his gallery contact, Henry Wallis, and eighty-nine to his friend Gambart.[19] These were to form the basis for his exhibition of December 1870. Durand-Ruel later wrote: “On my arrival in England then, I found myself with a wonderful set of first-rate works, the likes of which will never be seen again.”[20] In order to lend his first exhibition an extra cachet, he organized it under the auspices of what he called the Society of French Artists. This was initially led by a committee of seven artists: Daubigny, Diaz de la Peña, Dupré, Eugène Fromentin (1820–76), Eugène Isabey (1803–86), Millet, and Gustave Ricard (1823–73).[21] Durand-Ruel was the director of the society and Arthur Hutton the secretary. The committee was made up principally of Barbizon painters, thus further reinforcing the importance of this group of artists to the exhibition and Durand-Ruel’s project.[22] Daubigny was in fact in London with Durand-Ruel in the fall of 1870, and, on October 15, wrote that he had been to see the dealer, who intended to found “a serious establishment.”[23] A few days later, Daubigny noted that Durand-Ruel had opened his gallery and had also commissioned three paintings from him based on his studies of the Norman coastal port of Villerville.[24] At least one of these was probably in the December 1870 exhibition. Dupré, Millet, and Fromentin, for their part, maintained close contact with the dealer from France; so, too, did Diaz de la Peña, from Brussels.

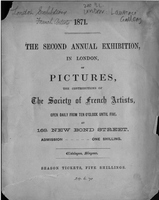

Durand-Ruel’s space on 168, New Bond Street had an advantageous location in Mayfair, strategically chosen by the dealer to be close to other major galleries which were concentrated around Piccadilly. Exhibition catalogues and press reviews indicate that there were two galleries, one on the ground floor and one on the first floor, which Durand-Ruel described as “fairly spacious.”[25] Unfortunately, there are no extant gallery plans or prints or photographs of the installations. Often exhibitions were anchored by major large-scale paintings, with many smaller works surrounding them. The introduction of a one-shilling entrance fee from the second exhibition onward emphasized the space’s exclusive character, and the publication of an accompanying catalogue, also for every exhibition from the second onward, further increased the exhibition’s cachet (fig. 1). These catalogues were priced at sixpence each, which was the same price as the catalogues for Gambart’s exhibitions, while those of the Royal Academy cost one shilling. From 1873 onward, there were two exhibitions a year, one in the spring, when the Royal Academy exhibition attracted potential buyers, and the other in the fall. Based largely on press reviews, this article identifies for the first time many of the Barbizon paintings in these exhibitions.

The First Two Exhibitions, 1870–71

Durand-Ruel’s first exhibition of the Society of French Artists relates to a growing discourse around the way in which war impacts collecting trends and patterns. The dealer’s year-long stay in London, from September 1870 until September 1871, and the transfer of his painting stock from Paris to the safety of London, was necessitated by the Franco-Prussian War. As Tom Stammers has noted, this war was an important “engine of cultural change.”[26] Durand-Ruel’s first exhibition contained two distinct hangs, the first of 108 paintings and the second of 144, with the dealer rotating and adding several works in early 1871. The initial hang, which opened at the start of December 1870, was an eclectic mix of work, with Barbizon paintings making up close to half of the display. A range of large-scale paintings were exhibited as well as smaller pictures, including preparatory studies. Durand-Ruel almost certainly saw the gallery’s viewing conditions as offering a more intimate counterpoint to the large spaces of the Royal Academy. Daubigny’s works, for example, had often been poorly hung at the Academy.[27] There is a typed, hand-annotated listing of works from the Durand-Ruel gallery for the two hangs of the first exhibition, but no formal catalogue survives.[28] As a result, it is often necessary to turn to press reviews to identify works. Six paintings by Rousseau included a very large winter-sunset scene that can be identified, from a review in Art Pictorial and Industrial, as the enormous Forest in Winter at Sunset (fig. 2), the largest picture that Rousseau ever produced and arguably his masterpiece.[29] One press review mentioned that Forest in Winter was hung opposite the enormous General Prim (1869; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) of Henri Regnault (1843–71).[30] There were also Rousseau’s two large decorative panels, Morning and Evening (figs. 3, 4), from the collection of Prince Paul Demidoff.[31] Corot showed eight paintings, including the large mythological scene Circle Dance of Nymphs (1870; private collection, R2002), shown at the Paris Salon of 1870, and Ville-d’Avray (fig. 5).[32] Daubigny exhibited eight paintings, among which was On the Banks of the Oise (location unknown), recently shown, and unfavorably “skied,” at the Royal Academy exhibition of 1870.[33] Dupré showed sixteen pictures, more than any other artist, including several marines, such as, probably, The Headland (fig. 6).[34]

The reviewer for The Times reinforced the significance of the exhibition while also recognizing the importance of the war in leading to it: “In sober truth it is hard to over-estimate the influence of the very remarkable collection of pictures which recent calamities have driven from Paris to a place of safety in London.”[35] The landscape paintings on view particularly attracted critical attention. The Observer reviewer described “an unusually rich collection of works by the most esteemed French painters of landscape” and noted that these were characterized by “their low toned luminous skies, massing of shadow, and carelessness of detail, and their general gravity of feeling.”[36] The Times critic noted, “French landscape painters, unlike the reigning English school, as a rule, paint impressions and not transcripts. . . . Elaboration of detail is avoided.”[37]

Durand-Ruel’s correspondence to Fromentin highlights his hopes for this first exhibition. He wrote in January 1871: “It’s . . . my greatest wish to make our beautiful French school accepted and loved here and I hope to succeed.”[38] Always deeply patriotic, Durand-Ruel undoubtedly saw his exhibition as a way of affirming France’s supremacy in the sphere of culture at the very same time that the nation was facing humiliation at the hands of the Prussians during the siege of Paris in the winter of 1870–71. Ironically, the gallery that Durand-Ruel rented at 168, New Bond Street, was known as the German Gallery, a title that dated to the early 1850s.

On March, 6, 1871, Durand-Ruel opened a rehang of much of the installation, replacing several paintings and adding works to increase the total number of pictures on view to 144.[39] Approximately eighty works were now newly on view. This second hang built on the favorable critical response to the first installation. The general character of the exhibition remained the same, with Barbizon paintings still central. Among the most notable changes were the addition of the large-scale paintings Orpheus Greeting the Dawn (fig. 7) and The Sleep of Diana (1865–68; private collection), by Corot.[40] A commentary in the Saturday Review in April 1871 described Corot as “an artist of rare intuition brought almost for the first time to the knowledge of Londoners in the present gallery.”[41] Also added to the exhibition were the related large-scale panels Morning and Evening (figs. 8, 9), by Dupré.[42] There were now three paintings by Millet including The Wood Sawyers (fig. 10) and probably the Cliffs at Gruchy (1870–71; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), simply titled Marine View. Millet had recently sent two pictures to Durand-Ruel from his studio at Gruchy on the Normandy Coast.[43] Dupré’s installation also likely included paintings sent by the artist from his studio at Cayeux on the north coast of France. In his correspondence with Durand-Ruel, Dupré worried that his works would be “too violently painted” for “your amateurs.”[44] He was aware of the critical controversy around the thick impasto in his paintings, and was concerned as to whether such works—and such a style—would find a market in England where, in his opinion, collectors generally leaned toward precision of finish.[45]

The second hang attracted some critical attention. A review in The Observer noted that “the beautiful studies of landscape . . . still constitute the chief strength of this gallery.”[46] This reviewer picked out the new installation of Corot’s two “large classical landscapes” while noting that they were not conducive to more “direct” English taste.[47] There were now eighteen works by Dupré on view. The critic for the Saturday Review emphasized the difference of Barbizon painting from the work of contemporary English landscapists: “Our English painters, it may be said, hold the mirror up to nature; their transcripts are photographic, uncolored by emotion. . . . On the other hand, French landscape painters approach nature with passion, their eye kindles with the fire of frenzy, and is sometimes shaded with melancholy.”[48] This reviewer also drew a comparison between the Barbizon artists and an earlier generation of British painters, including John Constable, who painted in a looser, more gestural style.[49] The growing interest in Constable’s work in the 1860s and 1870s in Britain may, indeed, have been a contributing factor to a rise in the taste for Barbizon paintings.[50] For example, the banker Louis Huth (1821–1905), to whom we shall turn later, had acquired Constable’s Hadleigh Castle, The Mouth of the Thames – Morning after a Stormy Night (1829; Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection, New Haven) by 1863, at least ten years before he first purchased works by Corot.[51]

The Second Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists ran during the summer of 1871. It was particularly notable for the inclusion of Laurent-Richard’s spectacular collection, which Durand-Ruel had shipped over from Paris. This collection had previously attracted significant press attention in France and was especially strong in Barbizon landscape paintings, with thirteen works on view by Rousseau, including Hoarfrost (fig. 11), ten by Dupré, seven by Troyon, and four by Corot. The reviewer for The Athenaeum highlighted the pictures by Rousseau: “Among thirteen superb works by Théodore Rousseau we can now only note the gorgeous Autumn Effect, the magical Moonlight, the wonderful rich and beautiful Le Givre [Hoarfrost]—a picture of hoary frost on the earth, under a sky which has rarely been surpassed in its wild grandeur.”[52] This collection attracted the attention of British collectors and dealers of Barbizon painting. In April 1873, indeed, Laurent-Richard sold off much of his collection of Barbizon painting, with some success, in an auction in Paris that was widely reported in the press in Britain.[53] To take a single example, The Edge of the Forest of Clairbois, Fontainebleau (fig. 12), was bought at the auction by Durand-Ruel and subsequently sold to the Scottish industrial chemist and collector, James Donald (1830–1905), though the precise details of the acquisition are yet to be established.[54]

Exhibitions of the Society of French Artists, 1872–74

Durand-Ruel returned to Paris in September 1871, leaving the London gallery under the management of his colleague, Charles Deschamps (1848–1908). In the years that followed, Durand-Ruel orchestrated seven more exhibitions, in which Barbizon pictures remained crucial. Durand-Ruel concentrated on those Barbizon painters who were still alive and with whom he remained in close contact. These exhibitions contained major pictures by Millet and Corot as well as a range of their smaller works, and undoubtedly led to the expansion of the market for both artists in Britain. Durand-Ruel had acquired many of these pictures directly from the two artists themselves before shipping them directly to London. There were also many works by Dupré and Daubigny. In contrast, there were far fewer paintings on view by the deceased Rousseau and Troyon.

The Third Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists ran from February to April, 1872, and was particularly notable for the display of twelve pictures by Corot including Evening, the largest picture in the exhibition, which can probably be identified as The Crossing of the Ford: Evening (ca. 1865–70; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rennes, Rennes).[55] The painting had been shown at the 1868 Salon and, as we shall see, would later be acquired by the Scottish collector James Duncan (1834–1905).[56] There were also two pictures of nymphs, described by one reviewer as “conventional in subject . . . but . . . certainly not so in execution.”[57] Corot’s works attracted the greatest press attention, with The Observer reviewer noting the artist’s “twelve silvery gems.”[58] Millet also exhibited two significant landscapes, Returning Home (1863; location unknown) and Winter (1862; Belvedere, Vienna). Dupré, for his part, was represented with a selection of twelve paintings.

The society’s fourth show, which ran from May 1872, was distinguished by the display of Millet’s two major pictures, The Angelus (fig. 13) and The Water Carrier (1855; private collection, Japan). Both were extensively praised in the press.[59] The comments of the female critic, E. F. S. Pattison (1840–1904), also known as Lady Dilke, who would become an increasingly important critical voice in the 1870s, are especially notable. She wrote that “everything which Millet does affords matter for study, for interest, for admiration,” and expressed particular enthusiasm for The Angelus, in which “the suggestive exaltation of the woman’s attitude makes her figure a poem in itself, of which the full charm and loveliness can only be realised by long looking.”[60] The fifth show, in the fall of 1872, was again largely dominated by the work of Millet. The reviewer for The Examiner noted: “As has been the case in former exhibitions at M. Ruel’s gallery, the works of M. J. F. Millet . . . are entitled to take precedence of all the others.”[61] The works now on view included Sowing, identifiable as The Sower (1850; Yamanashi Prefectural Museum of Art, Kofu), Death and the Woodcutter (ca. 1858–59; Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen), and Pasture near Cherbourg (Normandy) (fig. 14). As a group, this was a major display. The appearance of The Sower and Death and the Woodcutter, in particular, were part of Durand-Ruel’s systematic effort to promote these works on the international stage, having acquired them earlier in 1872 for significant sums.[62] Millet was well aware of the success of this show. His friend and agent, the civil servant Alfred Sensier (1815–77), wrote to him on December 4, 1872, reporting extracts from the Pall Mall Gazette by “the most famous of English critics.”[63] Sensier was here referencing the critic Sidney Colvin (1845–1927), who described Millet as “the Patriarch of Fontainebleau, the most poetical of the democratic school of French painters.”[64] The commentator for the Saturday Review also noted the importance of Durand-Ruel’s exhibitions for popularizing Barbizon painting in Britain: “The use of this Society of French Artists has been to give importance to such painters as MM. Corot, Dupré, Rousseau, Millet and others, who had in England hitherto enjoyed only a select following among small coteries of artists and connoisseurs.”[65] The same reviewer compared Millet’s Sowing to John Everett Millais’s (1829–96) The Parable of the Tares (1865; Birmingham Museums and Art Gallery, Birmingham), which showed the “same subject” but was treated “with less imaginative insight.”[66]

The sixth exhibition, which opened in the spring of 1873, included a strong group of pictures by Corot. The reviewer for The Examiner noted: “At no previous exhibition in this gallery, or in this country, has J. B. C. Corot been so well represented as he is in the present collection, to which he has contributed seven works, all worthy to rank among his best productions.”[67] Millet’s The Goose Girl at Gruchy (ca. 1854–56; National Museum Cardiff, Cardiff) was one of three of the artist’s works exhibited. By 1878, this painting had been acquired by the Glasgow railway magnate John McGavin (1814–81), who formed an important collection of Barbizon pictures.[68] Dupré also showed his masterpiece, the large-scale Environs of Southampton (fig. 15), which Durand-Ruel had recently acquired for the very large sum of 42,000 francs at the posthumous sale of the Scottish entrepreneur Daniel Wilson (1790–1849), who was the first British collector to acquire Barbizon works.[69] Corot was again well represented in the seventh exhibition with eight paintings, most notably his large-scale, vertical landscape, A Pastoral (Une pastorale) (fig. 16), which had appeared recently at the Paris Salon. The reviewer for The Athenaeum noted: “‘Une Pastorale’ (66) is an ‘upright’ landscape, with figures dancing under the arching boughs, a vista of the sea and coast, and buildings on a cliff in the distance. . . . It is one of the masterpieces of the master.”[70] Millet showed his large-scale November (destroyed in 1945), an austere, compositionally innovative work that was arguably the culmination of his landscape practice and which attracted mixed critical reaction.[71]

Corot’s prominence continued in the eighth exhibition, in the spring of 1874, with nine paintings, the most of any artist. These included the large-scale religious picture Saint Sebastian Succoured by Holy Women (fig. 17), which won extensive praise.[72] Three pictures by Daubigny were shown, including St. Paul’s from the Surrey Side (fig. 18), which was described in The Athenaeum as a “learned and masterly study.”[73] At the ninth exhibition, in the fall of 1874, Corot showed another major work, Dante and Virgil (1859; Museum of Fine Arts, Boston), which was criticized for the poor drawing of the figures.[74] This exhibition was also notable for powerful works by Millet including The Old Stone House, now known as The Old House at Nacqueville (ca. 1871–72; private collection, US), and thirteen drawings, among them The Angelus, which was probably the pastel version (fig. 19) of this subject and which would later be acquired by James Staats Forbes (1823–1904).[75] Millet’s display was reviewed with high praise by the noted critic William Michael Rossetti (1829–1919):

Perhaps the chef d’oeuvre of the whole exhibition is The Old Stone House by Millet. . . . The solid weather-worn house stands behind a rounded grassy foreground. . . . This is a picture whose very simplicity leads the mind into an examining and brooding mood. In the upper of the two rooms is a highly interesting series of drawings by Millet, thirteen in number. They are mostly in black chalk or charcoal; some of them have touches of tinted chalk, or washes of colour, which, in two of the set, count for something considerable in the general effect. The finest of all is The Angelus; an admired composition in which two peasants, a man and a woman, at work in the fields, bow their heads, still standing upright, as they hear the church bell. Not only for grave simplicity and for sentiment, but for luminosity as well, this design is pre-eminent.[76]

Durand-Ruel withdrew from the Society of French Artists at the end of 1874, after having overseen nine exhibitions in total. In his memoirs he later noted that the gallery “was costing me a lot to run, over 125,000 francs per year, and income did not cover expenses.”[77] He sold the gallery to Deschamps, the nephew of Gambart, who had previously been the secretary of the society. From 1874, Deschamps was supported by Forbes as a silent partner.[78] Thereafter, there were two more exhibitions of the Society of French Artists, both in 1875.[79] Corot was prominent in both, with his lyrical Souvenir of the Environs of Lake Nemi (1865; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago) attracting particular attention in the eleventh exhibition.[80] Rossetti wrote: “There can be few finer or more important Corots to be seen anywhere than The Lake of Némi, in which a young man is seen helping himself up the bank after bathing. This is truly the work of a master; telling in charm of light—free, strong, and finely-composed in its forms.”[81]

A twelfth exhibition was held in 1876, although by then no longer under the auspices of the Society of French Artists. Then the gallery closed, with Durand-Ruel later blaming this on Deschamps’s lack of business diligence and his attraction to the “social whirl.”[82] Over their duration, the exhibitions of the Society of French Artists had generated an extensive critical discourse to which the most prominent critics of the day—Pattison, Rossetti, and Colvin—had contributed. Such writings undoubtedly played their part in the embrace of Barbizon painting in Britain, setting the stage for the important texts of William Ernest Henley (1849–1903) and David Croal Thomson (1855–1930) in the following decade.[83]

Sales and commercial success

To what extent were the exhibitions of the Society of French Artists commercially successful? As early as January 18, 1871, Durand-Ruel wrote that he had sold “several paintings” by Corot, Dupré, Daubigny, and Félix Ziem (1821–1911).[84] At around the same time, Dupré wrote to Durand-Ruel that he had also heard the exhibition was doing well.[85] In his memoirs, Durand-Ruel noted that he did enjoy “relative success” during his time in London from 1870 to 1871, which enabled him to raise his prices slightly.[86] The Durand-Ruel stock books record the sale of a large number of works by Barbizon artists in London in 1870 and 1871, although they do not identify the names of the individual buyers, presumably because the stock books were written in Paris and did not include more detailed information on the buyers from the London office of the firm. Seven works by Corot, for example, sold for a total of 20,125 francs, including a Dance of the Nymphs (location unknown) for 2,500 francs, Morning (location unknown) for 5,000 francs, and Orpheus Greeting the Dawn (see fig. 7) for 5,000 francs.[87] At least three paintings by Rousseau were also sold during this time, at prices from 150 francs to 1,750 francs, although not the largest works such as Rousseau’s Morning (see fig. 3) and Evening (see fig. 4) or Forest in Winter at Sunset (see fig. 2).[88] Dupré’s paintings sold for higher prices, with Durand-Ruel selling a marine sunset for 10,300 francs.[89] In June 1871, Durand-Ruel sold Troyon’s Cows in a Landscape to Agnew for £519.15s.[90]

Durand-Ruel later reminisced that those British collectors and dealers who were influenced by his early London exhibitions, and became his clients as a result, were “Messrs. Murietta, Forbes, Ionides, Miéville, Huth” and the “art dealer Cottier,” as well as “other collectors in London and Glasgow.”[91] Of those mentioned by name, we can identify Forbes, Constantine Alexander Ionides (1833–1900), Jean-Louis Miéville (1808–97), Huth, and Daniel Cottier (1838–91). The “other collectors” included the Manchester industrialist Samuel Barlow (1825–93), the Aberdonian flour merchant John Forbes White (1831–1904), and the Glasgow sugar-beet refiner Duncan.

In general, these collectors formed a loose network in the 1870s embodying a new type of self-made British entrepreneur, who was highly cultivated, outward looking, and well-traveled. All were successful middle-class men who made their fortunes in banking and industry. White, Forbes, Ionides, and Duncan, in particular, all had strong business connections with Europe, which took them to its cultural centers. All developed a taste for the naturalism and the lack of finish that characterized the work of the Barbizon artists. On occasion, they had direct contact with the artists, as in the case of Forbes, who bought pictures from Corot.[92] It is also notable that many of these supporters were Scottish, with Glasgow, in particular, being a center for collecting Barbizon painting.

We can examine Forbes first, a railway magnate who was an important and influential early collector of nineteenth-century French paintings.[93] An Aberdonian by birth, Forbes became Durand-Ruel’s first distinguished Francophile Scottish client and, by the dealer’s own account, a close friend.[94] Forbes paid Durand-Ruel 3,125 francs for Daubigny’s Sunset at Villerville,[95] possibly the painting of this title that Durand-Ruel included in the first hang of the first exhibition. Since Durand-Ruel served on the committee that organized the French section of the London International Exhibition at South Kensington in 1871, he would have recognized Forbes as the most prominent British lender of French pictures. Forbes loaned eight paintings, which included works by Corot, Daubigny, and Diaz de la Peña.[96] Prior to 1870, Forbes owned no works by these artists, and it is telling that his commitment to them coincided with Durand-Ruel’s first exhibitions.

Equally pioneering as a collector and promoter of Barbizon painting was White.[97] As early as 1868, in collaboration with the Scottish artist George Reid, he published anonymously Thoughts on Art and Notes on the Exhibition of the Royal Scottish Academy of 1868, a pamphlet whose authorship was ascribed to Veri Vindex (Claimant of Truth).[98] In the pamphlet, Corot, Courbet, Daubigny, and Millet were highlighted as the greatest landscape painters.[99] White’s manifesto was not only an invaluable account of his own taste but also connected him to the taste of his collector compatriots, who, like him, were ready to embrace the rural themes and tonal and stylistic qualities of Barbizon pictures in the early 1870s. It is also worth noting that White was a landscape photographer in his own right, whose photographs create atmospheric effects reminiscent of those in Barbizon paintings, notably the work of Corot. Moreover, from the 1860s, he was a noted collector of paintings by artists of The Hague School, a growing interest in which can be seen as further context for the emergence of Barbizon taste in Britain.[100] A number of the artists of The Hague School, such as Willem Roelofs (1822–97), studied at Barbizon, and their pictures were close in formal qualities and sentiment to those of the Barbizon painters.

Although there is no mention of White in Durand-Ruel’s memoirs, he was an early client. Either in 1872 or 1873 White bought from Durand-Ruel Corot’s Small River Landscape (La rivière), which had been exhibited at the London International Exhibition in 1871.[101] On September 3, 1874, White acquired Corot’s well-known Une pastorale (see fig. 16), which had been shown at the Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists in the fall of 1873. Later, this picture would become the first painting by Corot to enter a Scottish museum collection, when it was bequeathed by the sons of the Glasgow industrialist James Reid of Auchterarder (1823–94) to the Glasgow Corporation Art Galleries in 1896.[102]

The stockbroker Ionides was another important British client who purchased Barbizon paintings. He was a friend of the painter Alphonse Legros (1837–1911), who likely introduced Ionides to Durand-Ruel,[103] and an admirer of Jules Champfleury (1821–89), the influential French writer and theoretician of the Realist movement who had defended the paintings of the Barbizon artists.[104] Unlike Forbes and White, Ionides had been committed to purchasing contemporary French art since the mid-1860s. Ionides seems to have acquired Millet’s significant painting The Wood Sawyers by 1872, probably after seeing it at Durand-Ruel’s exhibitions.[105] Apparently he debated its merits relative to The Angelus (on view in the fourth exhibition) before ultimately deciding on its acquisition.[106]

The banker Huth is likely to have seen the early exhibitions in London and would certainly have attended the fifth exhibition in November 1872. Perhaps best known for his purchase of Degas’s Dance Foyer at the Opera (Foyer de la danse à l’opéra) (1872; Musée d’Orsay, Paris), Huth was also sensitive to the muted and sonorous tones of pre-Impressionist works, especially those of Corot. In the summer of 1873, Huth purchased from Durand-Ruel three Corots: one road scene and two with rivers, including Arleux-du-Nord, the Stream by the Road (fig. 20), which was then part of Durand-Ruel’s stock and possibly identifiable as The Fisherman on view in the seventh exhibition.[107] Both river scenes were reproduced in Huth’s sale catalogue of 1905.[108] These are cabinet size and show the hazily atmospheric treatment of landscape that had already proved so popular with French collectors from the 1850s onwards. Along with Forbes and White, Huth established himself as one of Corot’s most important early British collectors.

The Glaswegian dealer and collector Cottier was also an important buyer of Barbizon pictures. At the Seventh Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists, which opened on November 8, 1873, Durand-Ruel included Corot’s Une pastorale (see fig. 16), which was probably seen by Cottier, who was in London at that time.[109] In his memoirs for 1873, Durand-Ruel erroneously mentions “[James] Duncan” as the buyer of Une pastorale, but it was actually Cottier who acquired the picture before selling it to White for £950, as noted above.[110] At some point before 1877, Cottier also acquired Orpheus Greeting the Dawn (see fig. 7) and its pendant, The Sleep of Diana.[111] We may imagine that his interest had been encouraged by their earlier appearance in Durand-Ruel’s exhibition of 1871. These became centerpieces of his formidable collection of contemporary French art.[112]

From 1874, Duncan became Durand-Ruel’s most valuable London client, acquiring significant pictures by Corot, Courbet, Eugène Delacroix (1798–1863), Millet, and Rousseau. Early in 1874, at the dealer’s temporary premises at place St. Georges, Paris, Duncan was given a private view of some of Durand-Ruel’s most cherished French pictures. Following this, on March 16, the dealer sent Duncan a list of the works he had recently viewed, including “Rousseau, 2 grands tableaux en hauteur: matin [sic]; Soir,” (“two large, vertical paintings: Morning; Evening”) priced at 30,000 francs each.[113] These were the paintings that Durand-Ruel had shown in his first London exhibition, where Duncan may well have first seen them. In May, Durand-Ruel duly received a check from Duncan for the large sum of 75,000 francs, which in all likelihood included payment for the two Rousseaus.[114] Around 1874, Duncan also acquired Corot’s major The Toilette (La toilette) (1859; private collection).[115] On May 15, 1875, Durand-Ruel also noted that he had sold two of Millet’s pictures to Duncan.[116] These were Sheepshearers (ca. 1857–61; Art Institute of Chicago, Chicago) and Fishing Boat (1871; private collection, Brussels), which he had acquired—presumably on Duncan’s behalf—at Millet’s posthumous sale on May 10 and 11.[117] Corot’s Evening, almost certainly in the third exhibition in 1872, as we have seen, and Environs of Paris (1860s; The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York) were also acquired by Duncan, likely in the 1870s and probably after 1874.[118]

In 1874, Durand-Ruel also sold the large-scale St Sebastian Succoured by the Holy Women (see fig. 17) to the Manchester collector Barlow. This was shortly after its display at the Eighth Annual Exhibition of the Society of French Artists.[119]

Beyond its impact on collectors, there can be little doubt that Durand-Ruel’s London enterprise also had a significant influence on London and Paris dealers. For example, in the early 1870s, Agnew & Sons, who, as we have seen, had been selling Troyon’s work since 1856, broadened their range and number of Barbizon paintings, which were on occasion supplied by Durand-Ruel and another important Paris dealer, Francis Petit (1817–77).[120] The first Daubigny landscape listed in Agnew’s stock books was one of six French pictures sold by Petit to Agnew in October 1871.[121] In December that year, the Scottish banker David Plenderleath Sellar (1833–1901) purchased the Daubigny for £130.[122] In 1873, works by Corot, Diaz de la Peña, Dupré, and Rousseau appear in the stock books for the first time, some of these again supplied by Petit. Sellar acquired Rousseau’s Scene near Fontainebleau (location unknown), Viscount Powerscourt (1836–1904) bought Corot’s Landscape and River Scene (location unknown), and Price, who had already acquired four Troyons, bought his first landscape by Dupré, one of two that he eventually owned.[123]

The international print sellers and art dealers Goupil & Cie also benefited from Durand-Ruel’s promotion of Barbizon pictures in London. The Goupil company had operated in the English capital since 1841, and, in the early 1870s, doubtless aware of Durand-Ruel’s London campaign, it started to send Barbizon pictures to the London dealers McLean and Wallis.[124] Several English collectors, some of them clients of Agnew and Durand-Ruel, purchased works from Goupil’s premises at place de l’Opéra in Paris. In December 1871, for example, Sellar acquired Daubigny’s Landscape: The Washerwomen (Paysage: Les laveuses) (location unknown), and in January 1872, Diaz de la Peña’s Venus and Adonis (location unknown).[125] Goupil enjoyed particular success in selling Daubigny’s pictures to British collectors through the 1870s.[126] By 1878, for example, Forbes had acquired ten Daubignys from the dealer.[127]

Despite these other gallery sales, Durand-Ruel was undoubtedly the most important dealer in works of the Barbizon School in London by the 1870s, with his sales of large-scale paintings by Corot particularly notable. Durand-Ruel’s influence on Cottier was significant. According to an advertisement in The Athenaeum, in 1875 Cottier organized the largest exhibition of Corots ever seen in England.[128] Through Cottier’s agent, William Craibe Angus (1830–99), Barbizon pictures were sold to Glasgow collectors from the mid-1870s onward. By 1878, Angus had sold Corot’s The Little Bird Nesters (1873–74; Columbus Museum of Art, Columbus) to the Glasgow industrialist Andrew Maxwell (1828–1909), who had been a client of Durand-Ruel since 1872.[129] Other Glasgow dealers, such as Thomas Lawrie & Son, also began dealing in Barbizon pictures in the 1870s. It was likely Lawrie who, at some point before 1878, sold to McGavin Millet’s The Goose Girl at Gruchy, which, as we have seen, had featured in Durand-Ruel’s sixth exhibition.[130] Several other important collections of Barbizon art were formed in Glasgow, most notably that of Donald, who bought pictures from Angus and Lawrie. In 1882 Lawrie purchased Millet’s Going to Work (1850–51; Culture and Sport Glasgow [Museums]: Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum, Glasgow) on Donald’s behalf from Goupil.[131]

Aftermath

Durand-Ruel later remembered his gallery in England as being a failure, despite the success he had enjoyed in the early 1870s. As he noted, after the closure of his gallery “the popularity of works by the School of 1830 . . . came to a lengthy halt.”[132] He recalled that a collector like Forbes could have acquired the pastel of The Angelus (see fig. 19) in 1872 for 60 pounds but had declined to do so before ultimately acquiring the work in the early 1890s for the large sum of 4,000 pounds.[133] He also recollected that he had exhibited “in vain a multitude of superb works,” highlighting in particular those by Millet, notably the painting The Angelus (see fig. 13).[134] Despite the dealer’s negative recollection, The Angelus was in fact acquired by the Paris-based English collector John Waterloo Wilson (1815–83) shortly after the close of the fourth exhibition.[135] A taste for Barbizon painting would continue in Britain.

Evidence has yet to emerge about Forbes’s later acquisitions from Durand-Ruel, but his passion for Barbizon paintings, ignited by the dealer in 1870, did much to fuel the market for their pictures from the 1870s to the early twentieth century. As early as 1874 Forbes divested himself of seventeen works by Corot, Daubigny, Diaz de la Peña, Dupré, and Troyon. Christie’s handled the sale, thus raising the profile of these artists and the market value of their work.[136] This was followed by another sale in 1882.[137] Forbes’s passion for collecting led him to acquire over four thousand paintings, a substantial number of which were by members of the Barbizon School. At the time of his death in 1904 he owned 150 works by Millet and 160 by Corot.[138] His collection of Barbizon pictures was deemed too large to sell en bloc, so his executors sought to dispose of the paintings privately. Many of them were shown in an exhibition at the Grafton Galleries in London in 1905, which was widely publicized in the press and in scholarly art journals.[139]

Duncan, Ionides, and Forbes were generous lenders to important exhibitions of Barbizon art in Britain and Europe throughout the 1880s and 1890s. Duncan regularly lent pictures to the Royal Glasgow Institute of Fine Arts as well as to international exhibitions in France and Germany.[140] When his Barbizon paintings were sold in Paris by Theo van Gogh (1857–91) in 1886, they attracted the leading French collectors.[141] When Durand-Ruel decided to promote French art in America, he borrowed twenty of Duncan’s large paintings to spearhead his enterprise, including Rousseau’s Morning and Evening, the very pictures that the British public had first seen in December 1870.[142]

Had Duncan not sold his collection, there can be little doubt that he would have lent pictures to the Edinburgh and Glasgow international exhibitions held in 1886 and 1888, and to the Dowdeswell exhibition in 1889.[143] All three exhibitions featured first-rate Barbizon pictures. In 1896 the Royal Academy showed Ionides’s The Wood Sawyers (see fig. 10).[144] This painting attracted much attention in the press when Ionides bequeathed his entire collection to the Victoria and Albert Museum in 1900.[145] Just five years later Donald bequeathed to the Kelvingrove Art Gallery and Museum in Glasgow his important collection of Barbizon paintings, including Rousseau’s The Edge of the Forest of Clairbois, Fontainebleau (see fig. 12) and Dupré’s The Headland (see fig. 6), the first picture by Dupré to enter a Scottish gallery or museum.[146] As we have seen, these were the very same pictures that Durand-Ruel had first shown in Britain in his 1870–71 exhibition.

Conclusion

This essay has explored the efforts of Durand-Ruel to cultivate a market for Barbizon painting in Britain, the results of which are in accord with Lynne Ambrosini’s assertion that “it was from the period of Durand-Ruel’s stay in London that many of the leading British collections of ‘Barbizon art’ were formed.”[147] Durand-Ruel’s strategy for his London exhibitions achieved his ambition of bringing together a body of innovative French paintings, most notably landscapes, that emphasized their difference from the work of the contemporary English school. In the first two exhibitions of the Society of French Artists almost 50 percent of paintings shown were by Barbizon artists. Across a five-year period, some 1,616 pictures appeared, of which 347, or approximately 22 percent, were Barbizon paintings. These attracted the greatest attention in the press. As we have seen, major works by Corot, such as Orpheus Greeting the Dawn, Sleep of Diana, Saint Sebastian Succoured by Holy Women, and Une pastorale, appeared in these exhibitions and were then sold to British collectors. So, too, were important paintings by Rousseau, notably Morning and Evening, and Millet, principally The Wood Sawyers and The Angelus. Other works by Dupré and Daubigny were also exhibited and sold. Many other seminal Barbizon paintings were shown, subsequently returning to France, for example, Rousseau’s Hoarfrost, Millet’s The Sower, and Corot’s Dante and Virgil. The exhibition of so many significant works over the years undoubtedly helped to build market interest in Barbizon work, as was Durand-Ruel’s intention.

Durand-Ruel’s commercial enterprise in Britain from 1870 until 1875 has been seen as a failure, in stark contrast to his subsequent conquest of the US market.[148] Although he never enjoyed the same success in Britain as he did in the US, this article has demonstrated that he succeeded in developing vital connections with important British collectors at an early stage in his career. Critical response to his London exhibitions was also significant. The exhibitions of the Society of French Artists organized by Durand-Ruel represented a crucial moment in the developing taste for paintings of the Barbizon School in Britain.

Acknowledgments

Thanks to Paul-Louis Durand-Ruel, Flavie Durand-Ruel, and Max Donnelly for their generous assistance with the research for this article. Thanks also to Anne Helmreich and Sarah Herring for their helpful comments on a draft of the article.

Notes

[1] The reviewer also wrote: “Some of the most famous works of the school are here, and the history of French art for the last eighty years is revealed to us in a series of masterly productions ranging from Greuze and David to Daubigny and Regnault.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists at the German Gallery, Bond Street,” Art Pictorial and Industrial, February 1871, 177–78.

[2] In discussing the Barbizon artists, this article focuses on the eight painters (also including Charles Jacque) identified in David Croal Thomson’s The Barbizon School of Painters (London: Chapman and Hall, 1890). Thomson had first used the term “the Barbizon School” in an article on Corot in 1888. David Croal Thomson, “The Barbizon School, Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot,” The Magazine of Art, vol. 11, 1888, 182–85.

[3] For Durand-Ruel’s wider support of these artists, see Simon Kelly, “Durand-Ruel and ‘La Belle École’ of 1830,” in Inventing Impressionism: Paul Durand-Ruel and the Modern Art Market, ed. Sylvie Patry, exh. cat. (London: National Gallery, 2015), 54–75.

[4] See Jan Dirk Baetens and Dries Lyna, “The Education of the Art Market: National Schools and International Trade in the ‘Long’ Nineteenth Century,” in Art Crossing Borders: The Internationalisation of the Art Market in the Age of Nation States, 1750–1914, ed. Jan Dirk Baetens and Dries Lyna, exh. cat. (Leiden, the Netherlands: Brill, 2019), 15–63. Baetens and Lyna describe the way in which Durand-Ruel sought to market his stock in London as a national “brand.” They note the riskiness of his venture at a time when Barbizon art was “only beginning to be accepted as serious art even in his own country” (15).

[5] Anne Robbins, “Durand-Ruel’s Conquest of London,” in Patry, Inventing Impressionism, 170–93.

[6] Durand-Ruel’s father, Jean-Marie, was a friend of Arrowsmith. Paul Durand-Ruel, Memoirs of the First Impressionist Art Dealer (1831–1922), rev. ed. (Paris: Flammarion, 2014), 3. Although it is not known if Arrowsmith found buyers for the pictures by Dupré, Rousseau, and Troyon that he exhibited, they were well received in the press. Edward Morris, French Art in Nineteenth-Century Britain (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2005), 151–52.

[7] Rousseau’s exhibition in 1862 included The Pond (Musée de Reims). Corot visited the English capital to see his display in this year.

[8] Daubigny, who had good contacts with England, showed at the Royal Academy in 1866, 1867, 1869, and 1870, with Corot showing on a single occasion in 1869. For Corot’s exhibition, as well as his connection to England, see Michael Clarke, “Corot et Angleterre,” in Corot, un artiste et son temps: Actes des colloques organisés au Musée du Louvre par le Service culturel les 1er et 2 mars 1996 à Paris et par l’Académie de France à Rome, villa Médicis, le 9 mars 1996 à Rome, ed. Chiara Stefani, Vincent Pomarède, and Gérard de Wallens (Paris: Klincksieck, 1998), 175–89.

[9] For the Gambart gallery, see Pamela M. Fletcher, “Creating the French Gallery: Ernest Gambart and the Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery in Mid-Victorian London,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 6, no. 1 (Spring 2007), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/. For the wider structural context of the London art market, see Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich, with David Israel and Seth Erickson, “Local/Global: Mapping Nineteenth-Century London’s Art Market,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 11, no. 3 (Autumn 2012), http://www.19thc-artworldwide.org/. See also Pamela Fletcher, “Shopping for Art: The Rise of the Commercial Art Gallery, 1850s–90s,” in The Rise of the Modern Art Market in London, 1850–1939, ed. Pamela Fletcher and Anne Helmreich (Manchester, UK: Manchester University Press, 2011), 47–64; and Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, “The Lu(c)re of London: French Artists and Art Dealers in the British Capital, 1859–1914,” in Monet’s London: Artists’ Reflections on the Thames, 1859–1914, by John House, Petra ten-Doesschate Chu, and Jennifer Hardin, exh. cat. (St. Petersburg, FL: Museum of Fine Arts, 2005), 39–54.

[10] The painter Frederick Goodall recorded the celebration of Troyon’s 1857 visit by eminent members of London society including Charles Dickens, Clarkson Stanfield, Daniel Maclise and William Macready: “the party was got up to do honour to the distinguished painter Troyon.” See Frederick Goodall, The Reminiscences of Frederick Goodall, R.A. (London and Newcastle-on-Tyne: Walter Scott, 1902), 126, 137. The first Troyon listed in Agnew’s Picture Stock Book was Going to Market, no. 1010, June 20, 1856. It was bought by Gambart for £63 in 1857. Agnew’s Picture Stock Book, NGA27/1/1/1 (1853–62), Thos. Agnew and Sons Archive, National Gallery, London.

[11] See Linda Whiteley, “L’école de Barbizon et les collectionneurs britanniques avant 1918,” in L’école de Barbizon: Peindre en plein air avant l’impressionisme, ed. Vincent Pomarède, exh. cat. (Lyon: Musée des Beaux-Arts; Paris: Reunion des Musées Nationaux, 2002), 100–107.

[12] Agnew’s Picture Stock Book, NGA27/1/1/1 (1853–62), no. 1018; and Agnew’s Picture Stock Book, NGA27/1/1/3 (1865–71), no. 4612, Thos. Agnew and Sons Archive, National Gallery, London. Thanks to Brian Carpenter, archivist, Devon Archives and Local Studies Service, for confirming Price’s profession.

[13] Sarah Herring, The Nineteenth-Century French Paintings, vol. 1, The Barbizon School (London: National Gallery, 2019), 135, 141n148; and Catalogue de tableaux, dessins, études et croquis par Decamps: Tableaux & dessins par divers artistes, gravures anciènnes & modernes, lithographie, eaux-fortes etc. dont la vente aura lieu par suite de licitation après le décès de M. Decamps (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1865), 13, buyer Luquet, lot 31, Le matin (850 fr.), lot 32, Le midi (630 fr.), lot 33, Le soir (520 fr.), La nuit (510 fr.).

[14] Sarah Herring, “French Barbizon Landscapes Collected by Pre-Raphaelite and Aesthetic Movement Artists in the Second Half of the Nineteenth Century,” in The Pictor Doctus, between Knowledge and Workshop: Artists, Collections and Friendship in Europe, 1500–1900, ed. Ana Diéguez-Rodríguez and Ángel Rodríguez Rebollo (Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2021), 181–200; Sarah Herring, Nineteenth-Century French Paintings, vol. 1, 134–35; and Kenneth McConkey, “‘Silver Twilights’ and ‘Rose Pink Dawns’: British Collectors and Critics of Corot at the Turn of the Century,” in J.-B. Camille Corot: 1796–1875, ed. Gabriel Weisberg, exh. cat. (Tokyo: Art Life, 1989), 31. Leighton was also an admirer of Daubigny’s work and owned two pictures by the artist, though it is not known when he acquired them. By 1865 Leighton was on good terms with Daubigny, looking after him during his first visit to London and buying him oil tube paint and a sketchbook. Richard Ormond, “Leighton and His Contemporaries,” in Frederic Leighton: 1830–1896, exh. cat. (London: Royal Academy of Arts, 1996), 24; and Sally Woodcock, “Leighton and Roberson: An Artist and His Colourman,” Burlington Magazine 138, no. 1121 (1996): 526–28. Thanks to Sally Woodcock for confirming that Leighton sent the materials to Daubigny’s London address on Tuesday, July 11, 1865. For the most recent analysis of Leighton’s Daubignys, see Sarah Herring, “French Barbizon Landscapes,” 184–86.

[15] Howard Coutts, Adrian Jenkins, and Amy Baker, The Road to Impressionism: Joséphine Bowes and Painting in Nineteenth-Century France, exh. cat. (County Durham, UK: Bowes Museum, 2002), 58.

[16] Michael Kauffmann, Catalogue of Foreign Paintings II: 1800–1900 (London: Victoria and Albert Museum, 1973), 90, no. 194.

[17] Robbins, “Durand-Ruel’s Conquest of London,” 172–73; and John House, “New Material on Monet and Pissarro in London in 1870–71,” Burlington Magazine 120, no. 907 (1978): 637.

[18] In advance of the December show, Durand-Ruel exhibited, from October 29 until early December, a group of paintings that he had brought with him at McLean’s gallery in the Haymarket.

[19] Durand-Ruel’s daybook shows that he sent much work directly to Wallis at 120, Pall Mall, the address of the Gambart gallery: 7 works on August 29, 1870; 48 paintings on September 5; 25 paintings on September 9; and 10 framed paintings on September 19. Durand-Ruel also sent 41 works to Gambart in London on September 5, 1870 and 48 watercolors and oils to him on September 9. Nineteen paintings were sent to Perigueux on September 6. In March 1871, Durand-Ruel shipped the stock of his clients, including Faure and Goldschmidt. The art dealer Hector Brame (1831–99), with whom Durand-Ruel partnered, also brought work by Diaz de la Peña to London from Brussels.

[20] Paul Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 78.

[21] The extent to which these artists were involved in the choice of pictures is in fact unclear, and all may not have known initially about the Society of French Artists.

[22] Durand-Ruel wrote to Fromentin that it was “pour donner à mon exposition un cachet artistique et faire oublier le côté commercial.” Paul Durand-Ruel to Eugène Fromentin, January 18, 1871, in Barbara Wright, ed., Correspondance d’Eugène Fromentin, vol. 2, 1859–76 (CNRS-Éditions Universitas, 1995), 1627. From the second show, the committee expanded to include an eclectic range of seventeen members with not only Barbizon but also academic artists such as Alexandre Bida, Alexandre Cabanel and Hugues Merle. Corot’s name was added to the existing roster of Barbizon painters.

[23] “un établissement sérieux.” Charles François Daubigny to Julien de La Rochenoire, October 15, 1870, cited in Étienne Moreau-Nélaton, Daubigny raconté par lui-même (Paris: Henri Laurens, 1925), 102.

[24] “Durand-Ruel vient d’ouvrir une galerie et m’a commandé trois tableaux d’après mes études de Villerville.” Charles François Daubigny to Julien La Rochenoire, November 2, 1870, in Moreau-Nélaton, Daubigny raconté par lui-même, 104.

[25] Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 78.

[26] See Tom Stammers, “Salvage and Speculation: Collecting on the London Art Market after the Franco-Prussian War (1870–1871),” in Museums, Modernity and Conflict: Museums and Collections in and of War Since the Nineteenth Century, ed. Kate Hill (London: Routledge, 2020), 15–38.

[27] The poor hanging of Daubigny’s submissions to the Royal Academy was a subject of complaint among British critics from the mid-1860s. In 1866, Daubigny showed a moonlight scene, Moonrise (location unknown), which was hung too high. The following year he exhibited Thames at Woolwich (location unknown), which was hung too low.

[28] The Durand-Ruel archives conserve a typed list of the 144 works in the second hang. The paintings in the first hang can be worked out from handwritten annotations to this list as well as critical commentaries. A catalogue does not survive, although there is some evidence that there was one. Dupré thanked Durand-Ruel for sending a catalogue, noting that he had an English professor ready to translate it. See Lionello Venturi, ed., Les archives de l’impressionisme, vol. 2 (Paris: Éditions Durand-Ruel, 1939), 137–39. Durand-Ruel also mentioned in a letter to Fromentin that he was sending a catalogue. See Paul Durand-Ruel to Eugène Fromentin, January 18, 1871, in Wright, Correspondance de Eugène Fromentin, vol. 2, 1627.

[29] “The grand landscape of the collection is by Theodore Rousseau, who died about three years ago. It is entitled, a ‘Large Forest in Winter’ (70), and through the gaunt branches of the trees in Fontainebleau we catch the red gleam of the winter’s sun. The picture is on a very large scale, and when looked at from the proper distance the effect is grandly realistic.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists at the German Gallery, Bond Street,” 177–78. Durand-Ruel was attached to this painting and later acquired it for his own collection, so it is perhaps not surprising that he decided to bring it to London with him.

[30] “Opposite this forest scene hangs a life-sized portrait of General Prim.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists at the German Gallery, Bond Street,” 178.

[31] “Two large upright landscapes, by Theodore Rousseau, are of a very novel kind. They represent ‘Morning’ and ‘Night’ with great truth.” Anon., “Society of French Artists,” The Standard, December 27, 1870, 3.

[32] R2002 in the parenthetical information following the title Circle Dance of Nymphs is a reference to the painting’s number in Alfred Robaut, L’oeuvre de Corot: Catalogue raisonné et illustré (Paris: H. Floury, 1905). Ville-d’Avray can be identified from the following description: “the subject appears by means of a calm, softly-shining river, with a little village on its banks, and trees of softest foliage grouped in a meadow; behind, a line of darker boughs rises against the grey, tenderly-toned sky; a man is fishing, a woman gathering fallen wood.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists—German Gallery, New Bond Street,” The Athenaeum, December 17, 1870, 808.

[33] “In On the Banks of the Oise, M. Daubigny’s sober, rather sombre, yet very sweet feeling for French pastoral prevails. It is a river pastoral. Lush herbage, with white and yellow flowers, is on the bank; a few trees, disposed with consummate art, a distant slope of land stretching towards the water and marked with cottages, a warm sky, elements familiar enough to those who know the pictures of the French master. . . . If, as we are assured, this picture was that which, being ‘skied’ at the Academy this year, was invisible, it affords a new proof of the incompetence, ignorant prejudices, or jealousies of those who placed it there.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists—German Gallery, New Bond Street,” 808.

[34] The Headland probably appeared as “A Marine View” (no. 25) which was described by one reviewer as “a masterly picture of waves tumbling on sands.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists—German Gallery, New Bond Street,” 808. Durand-Ruel also acquired a variant picture entitled Marine Landscape (1870; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Rouen), which was reproduced in Galerie Durand-Ruel: Recueil d’estampes, gravées à l’eau forte, vol. 3 (Paris: Galerie Durand-Ruel, 1873), n.p., no. 141.

[35] Anon., “Exhibition of French Pictures,” The Times, December 19, 1870, 4.

[36] Anon., “Exhibition of the Society of French Artists,” The Observer, December 11, 1870, 4.

[37] Anon., “Exhibition of French Pictures,” 4.

[38] “C’est du reste mon désir le plus grand de faire accepter et faire aimer ici notre bonne École française et j’espère y réussir.” Paul Durand-Ruel to Eugène Fromentin, January 18, 1871, in Wright, Correspondance de Eugène Fromentin, vol. 2, 1626–27. Durand-Ruel also later wrote of his aim to organize “a series of exhibitions that would make an impression on all the men of good taste then in London, and which did much to reveal the talent of our great French artists to the English.” Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 79.

[39] The date of rehanging was noted in Anon., “Society of French Artists—German Gallery, Bond-Street” The Observer, March 5, 1871, 7.

[40] For Orpheus, see notes 87 and 112. The pendant work, The Sleep of Diana (Le sommeil de Diane), was purchased by Durand-Ruel and Brame on February 3, 1868, from the Paul Demidoff collection auction in Paris for 3,045 francs; subsequently sold to a banker and collector with the surname Mosler, who had originally introduced Durand-Ruel to Brame; and then purchased back by Durand-Ruel alone from this collector in 1872 for 6,000 francs. See Durand-Ruel stock book, 1868–1873, nos. 3870, 10,684, Archives Durand-Ruel, Paris. The painting was sold at Sotheby’s, New York, to a private collector on May 9, 2014. 19th Century European Art, auction cat. (New York: Sotheby’s, 2014), n.p., lot 77.

[41] Anon., “The Parisian Gallery, New Bond Street,” Saturday Review, April 29, 1871, 532–34.

[42] Like Rousseau’s paintings Morning and Evening, and Corot’s Orpheus Greeting the Dawn and Sleep of Diana, Dupré’s pictures had formed part of the decorative ensemble for the Russian aristocrat Paul Demidoff’s Paris residence, although they had never ultimately been installed together.

[43] “I have lately sent two pictures to Durand-Ruel, one big and one small.” Jean-François Millet to Alfred Sensier, February 27, 1871, cited in Julia Cartwright, Jean-François Millet: His Life and Letters (London: Swan Sonneschein; New York: MacMillan, 1896), 323. The art critic Théophile Silvestre, who was also at Cherbourg, seemed to reference one of these—The Cliffs at Gruchy—in a contemporary letter: “You would have been struck by the sea pictures which he has just sent to London. Would you like to know the subject . . . ? It is an intense and vivid recollection of the cliffs at Gruchy, near the Castel [a well-known promontory of rocks on the Gréville coast], with the sea, the wide sea as it is seen from the top of the towering rocks in its calm and infinite extent, under a far-reaching horizon bathed in misty sunlight.” Théophile Silvestre to Doctor Asselin, February 25, 1871, in Cartwright, Jean-François Millet, 324.

[44] “vos amateurs le trouveront . . . trop violemment peint.” Jules Dupré to Paul Durand-Ruel, March 5, 1871, in Venturi, Les archives de l’impressionisme, vol. 2, 70.

[45] See, for example, this review: “In the ‘Route’ and the ‘River Scene,’ for instance, there is a hurling of solid paint on canvas which is perfectly astounding. It is impasto with a vengeance, and yet how unerringly he does it.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists at the German Gallery, Bond Street,” 178.

[46] Anon., “Society of French Artists—German Gallery, New Bond Street,” 7.

[47] The reviewer for The Observer also noted Corot’s two smaller naturalistic paintings (On the Route [no. 48] and Ponds at Ville-d’Avray [no. 78]) which hung directly beneath the much larger Orpheus Greeting the Dawn and Sleep of Diana. Anon., “Society of French Artists—German Gallery, New Bond Street,” 7.

[48] Anon, “The Parisian Gallery, New Bond Street,” 532.

[49] “The works in the Bond Street Gallery by MM. Delacroix, Dupré, Troyon, Rousseau, Ziem, and others, prove that French artists have long looked at nature with imagination akin to the genius of Etty, Turner, and Constable.” Anon., “The Parisian Gallery, New Bond Street,” 532. See also the words of W. M. Rossetti: “M. G. Michel . . . recalls something of the style of Crome. The same English painter, along with Constable, may have influenced J. Dupré in his Land-Storm.” W. M. Rossetti, “The Society of French Artists,” The Academy, November 28, 1874, 594.

[50] See Ian Fleming-Williams and Leslie Parris, The Discovery of Constable (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1984), 52.

[51] Graham Reynolds, The Later Paintings and Drawings of John Constable (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1984), 199, no. 29.1.

[52] Anon., “Fine Art Gossip,” The Athenaeum, June 10, 1871, 728.

[53] See, for example, Anon., “Letter from Paris,” The Scotsman, April 17, 1873, 3; and Anon., “Sale of Pictures in Paris,” The Hour, April 9, 1873, 3. The Hour reported that the sale had realized £55,942 (1,398,550 francs).

[54] Catalogue des tableaux composant la collection Laurent-Richard, auction cat. (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1873), 49, lot 47. Durand-Ruel paid 33,500 francs (£1,340) for the picture. James Donald acquired the painting for £2,000 at some point between 1873 and 1886. “The Donald Bequest,” The Art Journal, vol. 67, 1905, 190; and Memorial Catalogue of the French and Dutch Loan Collection, Edinburgh International Exhibition, 1886, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: D. Douglas, 1888), 72, no. 95.

[55] “‘Evening’ . . . shows a still pool in the foreground, with oaks and ashes about it, and cattle standing at rest. It is painted, as is M. Corot’s habit, in a low key of grey, and it is in effect an exquisite study of chiaroscuro and graceful composition, but the chief charms of the work are to be found in the subtle tint of the mid-distance, a rosy grey, the marvellous representation of reflexions on the calm water, and the grading of a line of trees which carry the eye to the limits of vision.” Anon., “The Society of French Artists, New Bond Street,” The Athenaeum, February 24, 1872, 246. For the reference to the picture as the largest in the show, see Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Examiner, February 24, 1872, 205.

[56] The picture, with the title ‘Evening,’ was bought by Durand-Ruel from the artist. Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 61. It did not find a buyer in 1872, as it was still part of the dealer’s stock in 1873. Galerie Durand-Ruel: Recueil d’estampes, vol. 5, n.p., no. 263.

[57] Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Examiner, February 24, 1872, 204–5.

[58] Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Observer, February 18, 1872, 7.

[59] Anon. “The Society of French Artists,” The Examiner, May 18, 1872, 502.

[60] E. F. S. Pattison, “The Summer Exhibition of the Society of French Artists,” The Academy, June 1, 1872, 204. Pattison also describes the Water Carrier as “a large work,” facilitating the identification of this as the picture in Japan.

[61] Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Examiner, November 9, 1872, 1104. This reviewer considered this display to be “on the whole the finest that M. Ruel has brought together in London” and noted that it was slightly larger, covering two rooms rather than one.

[62] Kelly, “Durand-Ruel and ‘La Belle École’ of 1830,” 70–71. Durand-Ruel subsequently sent both works to the Vienna International Exhibition of 1873 after their display in London.

[63] Alfred Sensier to Jean-François Millet, December 4, 1872. Lucien Lepoittevin, ed., Une chronique de l’amitié: Correspondance intégrale du peintre Jean-François Millet (Le Vast, France: J. and L. Lepoittevin, 2005), no. 1392. For Colvin’s article, see Anon. [Sidney Colvin], “The Society of French Artists,” Pall Mall Gazette, November 28, 1872, 11.

[64] Lepoittevin, Une chronique de l’amitié, no. 1392.

[65] Anon., “Winter Exhibitions,” Saturday Review, November 30, 1872, 697–98.

[66] Anon., “Winter Exhibitions,” 698. It is possible that the turn of the leading British artist, Millais, to pure landscape in the 1870s may have contributed to the rise of the taste for Barbizon painting. Despite the high level of finish in Millais’s landscapes, the attention to atmosphere and light in works such as Chill October (1870; Lord Lloyd Webber Collection, UK) has been compared to Barbizon landscape imagery. See Anne Helmreich, “Poetry in Nature: Millais’s Pure Landscapes,” in John Everett Millais: Beyond the Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood, ed. Debra N. Mancoff (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2001), 149–80, esp. 152.

[67] W. W., “The Society of French Artists,” The Examiner, April 26, 1873, 440.

[68] The Goose Girl at Gruchy was exhibited in 1873 as The Gooseherd (no. 31). McGavin lent it, along with three other Barbizon pictures, to an exhibition that took place at the Glasgow Corporation Galleries in 1878. Official Catalogue of the Glasgow Fine Art Loan Exhibition in Aid of the Funds of Royal Infirmary Held in the Corporation Galleries, Sauchiehall Street, exh. cat. (Glasgow: Corporation Galleries, May–July, 1878), 4, no. 14 (The Geese-herd). For McGavin, see Frances Fowle, Impressionism and Scotland, exh. cat. (Edinburgh: National Galleries of Scotland, 2008), 23–24, 132.

[69] Catalogue des tableaux anciens et modernes et des tapisseries faisant partie de la collection de M. D. W [ilson], auction cat. (Paris: Hôtel Drouot, 1873), 32, lot 5; and Andrew Watson, “The Provenance of ‘The Death of Sardanapalus’: New Insights from Unpublished Correspondence,” Burlington Magazine 166, no. 1454 (2024): 472–73.

[70] Anon., “Society of French Artists, New Bond Gallery—Winter Exhibition at the French Gallery,” The Athenaeum, November 8, 1873, 601.

[71] One reviewer remarked, “There is a power in this picture very difficult to analyze, and still more difficult to resist.” Anon., “Society of French Artists,” The Art Journal, vol. 35, 1873, 368. Another praised the “solemn” picture while noting that “we should like to remove the lumpy foreground.” Anon., “Society of French Artists,” The Observer, November 2, 1873, 5.

[72] For the discourse around the Barbizon pictures at the eighth show, including the high praise from the critic of The Athenaeum for Corot’s Saint Sebastian, see Simon Kelly, “Les Impressionnistes à la huitième exposition de la ‘Society of French Artists’ à Londres au printemps 1874,” Revue de l’art, no. 223 (2024): 42–53.

[73] Anon., “Exhibition of the Society of French Artists,” The Athenaeum, May 9, 1874, 639.

[74] “The most conspicuous landscape in this collection is the Dante and Virgil of M. Corot . . . the landscape material is below his finer standard, and the figures are decidedly poor.” W. M. Rossetti, “The Society of French Artists,” 594.

[75] It is possible that this drawing was the black conté crayon The Angelus (ca. 1860; Walters Art Museum, Baltimore, 37.903). Durand-Ruel noted that he bought this at the John W. Wilson sale (April 27–28, 1874, Paris, lot 129) before sending it to his London branch where it sold for £200. Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 116, 265.

[76] W. M. Rossetti, “The Society of French Artists,” 594.

[77] Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 122.

[78] Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 122.

[79] Durand-Ruel seems to have continued to lend paintings to the shows, despite withdrawing his financial backing.

[80] For the tenth exhibition, see Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Athenaeum, May 22, 1875. For the eleventh exhibition, see Anon., “The Society of French Artists,” The Athenaeum, November 20, 1875, 678.

[81] W. M. Rossetti, “Fine Art. The Society of French Artists,” The Academy, November 27, 1875, 560.

[82] Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 122.

[83] In 1881, Henley, who knew Colvin, published Jean-François Millet: Twenty Etchings and Woodcuts Reproduced in Fac-Simile and a Biographical Notice (London: Fine Art Society, 1881). As editor of The Magazine of Art (1882–86) he published an article on the collection of Constantine Alexander Ionides, which drew attention to Ionides’s important Barbizon pictures, including Millet’s The Wood Sawyers. Cosmo Monkhouse, “The Constantine Alexander Ionides Collection,” The Magazine of Art, vol. 7, 1884, 36–44. Henley also wrote the introduction to, and individual entries on the artists in, the Memorial Catalogue of the French and Dutch Loan Collection, Edinburgh International Exhibition, 1886. This exhibition included the most important display of Barbizon painting yet held in Britain. Many of the French pictures were lent by Scottish collectors, such as James Donald and James Staats Forbes. For Thomson and his promotion of Barbizon painting, see note 2. See also Anne Helmreich, “David Croal Thomson: The Professionalization of Art Dealing in an Expanding Field,” Getty Research Journal, no. 5 (2013): 89–100.

[84] “Je suis toujours assez content de mon séjour a Londres. Il y a beaucoup à faire pour l’avenir. J’ai vendu plusieurs tableaux de Corot, Dupré, Daubigny, Ziem.” Paul Durand-Ruel to Eugène Fromentin, January 18, 1871, in Wright, Correspondance d’Eugène Fromentin, vol. 2, 1626.

[85] Jules Dupré to Paul Durand-Ruel, January 21, 1871, in Venturi, Les archives de l’impressionisme, vol. 2, 67.

[86] He later wrote: “My relative success [in London] enabled me not only to hold the prices of my paintings steady, but to raise them slightly.” Durand-Ruel, Memoirs, 81.