The Revolution Takes Form: Art and the Barricade in Nineteenth-Century France by Jordan Marc Rose

Reviewed by Erin Duncan-O’NeillErin Duncan-O’Neill

The University of Oklahoma

Email the author: erinduncanoneill[at]ou.edu

Citation: Erin Duncan-O’Neill, book review of The Revolution Takes Form: Art and the Barricade in Nineteenth-Century France by Jordan Marc Rose by Jordan Marc Rose, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.9.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Jordan Marc Rose,

The Revolution Takes Form: Art and the Barricade in Nineteenth-Century France.

University Park, PA: The Pennsylvania State University Press, 2024.

184 pp.; 35 color and 26 b&w illus.; notes; bibliography; index.

$109.95 (hardcover)

ISBN: 9780271095493

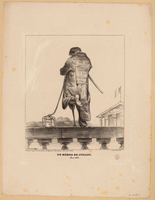

In one of the most moving passages from Jordan Marc Rose’s new scholarly monograph The Revolution Takes Form, the author describes Honoré Daumier’s A Hero of July, May 1831 (Un héros de Juillet, Mai 1831), a lithograph published in December 1832 (fig. 1). In the print, a veteran stands on a bridge balustrade facing the Chamber of Deputies. One foot disabled in the fighting of 1830, he is precariously balanced between a walking stick pointing toward the legislative chamber and a pavé (paving stone) tied by a rope that hangs ominously from his neck. Emblematic of most of the major works in this larger investigation on images of barricades, the structure or site of the barricade exists “offstage” (xi), acting for Rose’s purposes symbolically, as “cognitive framework” and “organizing structure” (xii). The paving stone here tethers the veteran to the violent realities of the past as a substitution for bodily wholeness and a worrisome view into the future where he, like the promises made by the new government forged on the barricades in 1830, may not survive long.

The veteran wears a coat sewn out of pawn receipts, which Rose deftly connects not only to the veteran’s obvious desperation but to the thin promises of the July Monarchy that, he says, were offered with the pawnbroker’s assumption that “the people” would not return to collect. Situating the lithograph with historical precision within the tumultuous events of 1830–34 and the nuanced signs of class the author reads so well (the coat an insubstantial imitation of bourgeois status), this passage also shows Rose’s impressive attention to medium. He argues that the sewn paper of the coat was also an opportunity for the artist to think through the utility of his own works on paper, their provisional place in history, and their effort to unify and signify through their mass, cheap dispersal.

Rose’s approach to medium is one of the great strengths of this book. Exploring images of violence and insurrection in the 1830s and 1840s, The Revolution Takes Form examines how revolutionary turmoil was pictured in the period when the visual language of barricades was forged in France. Each of its four chapters centers around case studies that interrogate representations of massacre and riot across multiple media (specifically, lithography, relief sculpture, and painting), weaving in supporting works in these diverse media to make important points about how the asynchrony of the project of representation is especially acute in images of political violence. In rendering provisional sites of rupture and death after they have been quelled and put back together, each key artwork contends with belatedness, nostalgia, failure, trauma, and uncertainty. Though the written word can articulate ambivalence and doubleness—and Rose’s book pulls substantially from period texts—the images he selects are particularly adept at rendering confusion in the aftermath, when the consequences of violence are not yet fully known.

Rose rightly introduces the book with a close look at Eugène Delacroix’s 1831 painting July 28, 1830: Liberty Leading the People (Le 28 juillet 1830: La Liberté guidant le peuple; Musée du Louvre, Paris), in part to lay out a key theme about how time is imagined in representations of the barricade. Through Liberty Leading the People, the reader is conditioned to see citizens as fulcrums between stones dug up from the past and projections (bodily and imaginatively) into the future. The artists in the rest of the book will render the forceful march into the future from a lens of hindsight that embeds pessimism, ambiguity, and futility in ways Delacroix did not. Rose’s introduction and preface might make slightly too much of the claim that figural orientation to the left of representational space—the direction of course of Liberty’s focused gaze—points to a future orientation while the right means the past, particularly because it is when Rose tackles the most complex compositions and conceptions of time that this book finds some of its most compelling insights. In addition to Liberty Leading the People, which appropriately acts as an inspiration, “foil,” and “limitation” (18) for representations of political insurgency over the next two decades, the book addresses three massacres and a riot, departing from the street at times to show the long, messy tremors of physical cruelty and political disappointment.

Chapter 1, “Trivial and Terrible Reality,” focuses on the sense of despair between 1831 and 1834, when the newly instantiated July Monarchy’s restrictions on assembly and press freedoms led to conflict between citizens and the government. Daumier’s lithograph Rue Transnonain, April 15, 1834 (October 1834) is famously a scene of state-sanctioned murder in a domestic space. Citizens were shot, stabbed, and beaten in their homes because of false claims of a sniper shooting down from a building as the army cleared a barricade during a brief, failed rebellion. Confining the scene to one room—though many apartments at no. 12 rue Transnonain had been breached—and even downplaying the gruesome nature of the murders conducted at close range, Daumier’s lithograph does not structure Rose’s chapter as such, but bookends an analysis of the disempowerment of the public during the early years of the July Monarchy. Because the so-called roi populaire (popular king) Louis-Philippe had emerged from the barricades of the July Revolution, he was sensitive to the degree to which his legitimacy relied on public opinion and collective action and quickly revoked the promised freedoms of press, assembly, and the right to bear arms, coming down with particular ferocity after 1834.[1] That Daumier’s print of martyred civilians became symbolic of the April 1834 uprisings is meaningful because while the print was certainly a powerful anti-government statement, it was unlike much of the visual record from 1830 and 1832 because it offered no heroes or even combatants, putting forth an unforgettable scene of unwilling victims, the kind of victims more likely to inspire widespread despair without necessarily moving the cause forward.[2]

The second chapter, “This is Not a Program,” centers on Auguste Préault’s Killing (Tuerie [fragment épisodique d’un grand bas-relief], 1834/51; Musée des Beaux-Arts de Chartres, Chartres), an experimental Romantic relief sculpture of twisting, tortured violence persuasively described as tearing at tradition and offering no grounded narrative. If the work’s slipperiness avoids a clear iconographic reading—and if meaning here is ultimately elusive—the chapter could make a clear case for its inclusion in the larger umbrella of this monograph perhaps with a sustained exploration of the closeness of violent contact between combatants, a framing theme in this book that was drawn from Frederick Engels’s description of the value of the barricades in civil conflict (ix). Looking back at the Second Republic, Engels argued that “the barricade produced more of a moral rather than material effect. It was a means to shake the solidity of the military.”[3] How to give this kind of moral or metaphorical impact material form? This is the project at the heart of this book, especially when art’s answers are provisional and messy.

The barricades offered in this study are never physically imposing. Rather than meaningful architectural barriers, they are a form of representation in themselves and thus an intuitive draw for artists. Chapter 3, “A Monstrous Pile of Men and Stone,” examines Ernest Meissonier’s Memory of Civil War (Souvenir de guerre civile; Musée du Louvre, Paris), a painting executed between 1848 and 1849 but held back from the Salon until 1851. The painting becomes a traumatic recollection of the failure of the promises of February 1848 made in the wake of June and the fall towards Empire. Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby supervised this project in its dissertation phase along with T. J. Clark, and like Grigsby’s influential analysis of Théodore Géricault’s Raft of the Medusa (1818–19; Musée du Louvre, Paris), Rose writes about the horror revealed in a tangle of corpses and traces the changes made from initial sketches to finished painting in terms of degrees of bodily completeness and physiognomic particularity.[4] Drawing from Clark, Rose includes extensive period criticism, a close analysis of markers of class in relation to the events of 1848, and a discussion of the status of fraternité (brotherhood) in 1850–51.[5]

There is an incredibly thoughtful discussion of space in relief sculptures in Rose’s analysis of both Préault’s Killing and Daumier’s Fugitives (Les Fugitifs, ca. 1848/49; Musée d’Orsay, Paris) in chapter 4. Rose argues that the artists exploited the compression of space both to block secure meaning, in the case of the first work, and to create, in the case of the second, an inhospitable nonspace for a community in flight. The compression into relief is, as the author describes, a violent act meant to communicate the torment of massacre and forced emigration to the embodied viewer. This approach prompted meaningful questions about the use of plaster and bronze to interrupt the viewer’s space—to barricade them into the artist’s vision.

The Second Republic frames chapter 4 as much as chapter 3, beginning with Charles Baudelaire as a lens on its dissolution and fall. It is in this arc that Rose sites Daumier’s The Uprising (L’Émeute; The Phillips Collection, Washington, DC), which is dated by its caption in the book to ca. 1848–52, but, as is made clear in the text, has a tricky genesis (even the Phillips Collection lists the painting with the expansive range of “1848 or later”). Rose acknowledges that dating this work is both “political” and “dangerous” (106) and rightly includes a lengthy discussion of likely contemporaneous works, including Workmen on the Street (Ouvriers dans la rue, possibly 1846–48; National Museum of Cardiff, Cardiff), The Rebellion (Une foule, ca. 1849; Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow), and Competition of 1848, Sketch of the Republic (1848; Musée d’Orsay, Paris). Ecce Homo (1849–52; Museum Folkwang, Essen, Germany) would perhaps have been a useful addendum because of its rhyming black contours, invocation of unruly crowds, and the symbolic potential of Christ as Republic.[6] The Uprising was only rediscovered by Arsène Alexandre in 1924. He called it “the most important and most impressive” of Daumier’s works.[7] It is, in spite of its sketchy origins and (for some) prohibitive authenticity issues, one of the most celebrated of Daumier’s canvases in North America. The disputed, heavily-outlined paintings of crowds, workers, and uprisings are worth grappling with, Rose tells us, not least because we see Daumier as an early painter interrogating the boundaries of Romanticism and Realism—of universality and contemporaneity—that haunt many works in this book and frame much of Daumier’s larger painterly project. Rose reads a sense of disappointment and dismay not usually cited in responses to The Uprising, which is typically seen as a heroic, visual Marseillaise: a “communion born of the finest hours in the life of a people.”[8]

Implicit in Rose’s emphasis on ambiguity in this work and others is the painful and faltering, sometimes abandoned, attempts by artists to balance historical specificity with universal abstractions. Delacroix’s Liberty Leading the People does this through its strange integration of realism and allegory in its soot-covered heroine. In the wake of this model, Daumier, Préault, and Meissonier struggle to find footing toward universality in painting and sculpture; Rose rightly reports that Rue Transnonain weaves the historical and the mundane together, layering the precision of a contemporary event with a meaningful, tableau-like scene of a generalized family felled. The author is more interested in productive “failures” of works like Killing and The Uprising and less in works that more confidently or legibly hold dialectical truths together. This kind of generative struggle embeds absences, cleavages, and marks of indecision that reflect, for Rose, feelings of despondency that remained after the barricades—after moments of historical regression, citizen sacrifice, and loss.

Rose offers a careful assessment of the physical support of artworks and how creatively artists exploited them, and the affinity between lithographic stones and pavers is skillfully embedded in the book’s approach. Rose writes compellingly about the quality of space in Préault’s relief sculpture, the layers of paint in Daumier’s The Uprising, and the differences between brushstrokes on wood and on canvas. With its close analysis of medium, this book could perhaps have made more of the material stuff of the barricades from July 1830, November 1831, June 1832, April 1834, and February and June 1848. It is curious how he gravitates toward images in which the barricades are so thin or outside representational space altogether. Others, including Daumier’s contemporaries Nicolas Toussaint Charlet, Henry Monnier, Hippolyte Bellangé, and Paul Gavarni offer more emphatic representations of the barricades’ wagons, furniture, barrels, stones, and smoke (fig. 2). For this book, it is more violence than site that Rose wishes to explore, and it is violence approached with historical specificity and acute attention to devastation, the regrets that often follow conflict. This is the reason Liberty Leading the People can act as both foil and limit and not be a key case study for this project. Like Daumier, Rose is suspicious of allegory and critical of narrative clarity when history is being forged. The author avoids heroic images, finding ambivalence even in Daumier’s Uprising, nuancing its rousing motif by pointing to a clumsy, scumbling execution that embeds the reluctance, contradiction, and indecision felt after the disastrous events of June 1848.

The Revolution Takes Form does a great service especially to Daumier scholarship, giving him his due with serious theoretical and formal attention. That this book grapples with several of Daumier’s paintings and reliefs with thorny dating and provenance issues is of great help moving the conversation forward. The author also carefully—and in an extremely insightful way—tethers Daumier and Préault together in 1834, placing his sustained attention on the relationship between medium and the representation of violence. What representational strategies and physical supports best capture historical moments that are so difficult and not easily fixed? Rose cites Charles Farcy’s 1834 assertion that “just as we would not want to see civil war perpetuated in reality, we are not very keen to see it perpetuated in painting.”[9] Unstable as these events are to begin with, their bewildered publics often want to move on, to forget their horrors. The quick cessation of imagery of the January 6, 2021, insurrection, an event that initially flooded newspapers and screens in the United States, is testament to this insight. Beyond occasional photographs of false shamans and a hangman’s scaffold, there is little appetite for looking back too closely and diagramming the waves of people surrounding the Capitol. Rose’s penetrating, incisive investigation of visual imagery from France in the 1830s and 1840s feels newly relevant in July 2024, when the discourse around political violence is the cause of diffuse, confusing despair, and the view from the future is ambiguous indeed.

Notes

[1] Jill Harsin, Barricades: The War of the Streets in Revolutionary Paris, 1830–1848 (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 107–10.

[2] Harsin, Barricades, 85.

[3] Frederick Engels, introduction to The Class Struggles in France (1848–50), by Karl Marx, ed. C. P. Dutt (London: Martin Lawrence, 1895), 23.

[4] Darcy Grimaldo Grigsby, Extremities: Painting Empire in Post-Revolutionary France (London: Yale University Press, 2002), 165–236.

[5] T. J. Clark, The Absolute Bourgeois: Artists and Politics in France, 1848–1851 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1973).

[6] See Henri Loyrette, Michael Pantazzi, Ségolène Le Men, and Édouard Papet, Daumier: 1808–1879 (Ottawa: Musée des Beaux-Arts du Canada, 1999), 274–75; and Clark, Absolute Bourgeois, 113–44.

[7] Arsène Alexandre, “An Unpublished Daumier,” The Burlington Magazine for Connoisseurs 44, no. 252 (1924): 143–44; and Loyrette et al., Daumier, 344.

[8] Jean Adhémar, “Les esquisses sur la Révolution de 1848,” Arts et livres de Provence 8 (1948): 44. Translation by the author.

[9] “et de même qu’on ne voudrait pas voir perpétuer en réalité la guerre civile, de même, on est peu désireux de la voir perpétuer en peinture.” Charles-François Farcy, “Salon de 1834,” Journal des artistes, March 23, 1834, 191.