L’ultimo ritratto: Mazzini e Lega, storie parallele del Risorgimento (The Last Portrait: Mazzini and Lega, Parallel Histories of the Risorgimento)

Reviewed by Stefano MoscatelliStefano Moscatelli

University la Sapienza

Rome

Email the author: stefanomoscatelli652[at]gmail.com

Citation: Stefano Moscatelli, exhibition review of L’ultimo ritratto: Mazzini e Lega, storie parallele del Risorgimento (The Last Portrait: Mazzini and Lega, Parallel Histories of the Risorgimento), Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.22.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

L’ultimo ritratto: Mazzini e Lega, storie parallele del Risorgimento (The Last Portrait: Mazzini and Lega, Parallel Histories of the Risorgimento)

Sala Zanardelli del Vittoriano, Rome

May 31–September 8, 2024

Catalogue:

Edith Gabrielli (with the historical advice of Giuseppe Monsagrati),

L’ultimo ritratto: Mazzini e Lega, storie parallele del Risorgimento, 2 vols.

Milan: Electa, 2024.

366 pp.; 132 color and 13 b&w illus.; index; list of exhibited works; bibliography.

€34.00 (softcover in hard slipcase)

ISBN: 9788892825963

The idea of retracing the events of the Risorgimento through the pictorial arts, supplemented with historical and archival documents, is both ambitious and civic-minded. It is more ambitious still to attempt to identify a point of contact between two parallel paths, retracing—at least in part—the lives of two vitally important nineteenth-century Italian figures: Silvestro Lega (1826–95) and Giuseppe Mazzini (1805–72). Lega was a painter, volunteer in the military campaigns of the Risorgimento and, although born in Romagna, very much had a Tuscan cultural background. Mazzini, widely referred to as “the father of the nation,” was an apostle of the ideological Risorgimento. Born in Genoa but exiled due to political reasons, he was the standard-bearer and principal supporter of the idea of a unified Italian republic. Forming the basis of the exhibition L’ultimo ritratto: Mazzini e Lega, storie parallele del Risorgimento, the stories of these two men necessitate being placed side by side or, in this instance, on two different floors of the exhibition, clearly distinguished by the routes and types of objects on display.

The first floor is entirely dedicated to painting; the second additionally features sculptures and documents (figs. 1, 2). Both floors stage the history of Italy during this crucial period in which it became a kingdom. The main narrative of the exhibition begins in 1848, a year of revolutionary uprisings across Europe, including the Cinque giornate di Milano (Five Days of Milan), and continues until 1872, the year of Mazzini’s death. There is, however, a sort of coda that focuses on the impact of Mazzini’s death and the figure of the patriot until the years immediately following World War II. The exhibition finds a perfect setting in the Monument to Victor Emmanuel II (1885–1911; Rome)—also known as “the Vittoriano,” a symbol of Risorgimento memory and the Italian monarchy—a monument to the “Third Rome” that Giuseppe Mazzini himself had prophesied and wished to see built on the Capitoline Hill (figs. 3, 4).

It is clear from the outset that the exhibition’s objective is not only to provide a biographical account of artistic representations of Mazzini and Lega, but also to give space to a long—and, I would say, accurate—reflection on the role of images in creating the “heroes of the fatherland.”[1] Indeed, the exhibition opens with Giovanni Spertini’s marble bust of Mazzini (fig. 5). The genesis and history of this work are explored in the second volume of the catalogue, which also offers a brief biographical profile of Spertini himself. Spertini’s career and artistic production represent the path of many sculptors who lived between the Risorgimento and the beginnings of the post-unification state. In the late 1830s and early 1840s, Spertini was the pupil of Pompeo Marchesi, a Brera sculptor who had studied with Antonio Canova in Rome. He was also a follower of Mazzini during the years of the second Italian war of independence (1859) and, ultimately, a sculptor engaged in the reproduction of mass-produced busts of both Mazzini and Giuseppe Garibaldi. Many citizens who voluntarily enlisted in the armies that faced the Austrians (in the Northeast) and the French (in Rome) held the fate of a united Italy close to their hearts, but this was especially true of many contemporary artists who were first and foremost patriots.

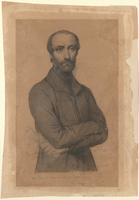

Like Lega, Spertini began producing busts in the 1860s, allocating part of his proceeds to funding battles and other patriotic causes, thereby initiating a veritable process of fundraising that would be difficult to imagine today if it were not for our knowledge of the social and political context during that time. Mazzini felt this desire as strongly as anyone: first in Marseilles, where in 1831 he founded Giovine Italia (The Young Italy), an organization whose manifesto is displayed in the first section of the exhibition (fig. 6), and then in London, where from the late 1830s onward some of his writings (including the essay “Modern Italian Painters” in the London and Westminster Review[2]) would be published in the British press. In this way, he helped to sow ideals and ideologies that would meet with a certain amount of success in Victorian England and that would be practically applied during his brief interlude as triumvirate of the Roman Republic of 1849. Luigi Calamatta, a little-known Roman engraver and painter, portrayed Mazzini in a now famous engraving (fig. 7) that shows the Genoese apostle placed halfway between the ancient ruins of the Colosseum and the dome of St. Peter’s, protected by the Vatican’s high walls: an almost messianic representation of the creator and prophet of the new Rome, a city that sought to be neither papal nor governed by a king, but that would finally be a free republic.

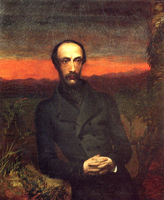

An essay by Maria Pia Critelli and Marco Pizzo in the catalogue helps to shed light on a theme that is varied, complex, and multifaceted, yet essential for understanding how the iconography of the fatherland’s “fathers” developed from the 1840s onward, years in which “political commitment itself seems to find a counterpart in the use of images” (1:83–103). It is thus that Emilie Ashurst Venturi’s famous Portrait of Mazzini (fig. 8), finds its place in the last room on the first floor of the exhibition. Ashurst was a writer, painter, and English translator of Mazzini, and her portrait represents one of the very first instances of what would become Mazzini’s characteristic iconography. The spectator’s gaze slowly moves from Mazzini’s clasped hands to the ring that was given to him by his mother, a woman loved and always remembered in exile. Similarly iconic are the black suit that he wore in mourning for the oppressed nation and his wide forehead, a detail upon which all representations—from paintings to sculptures through to reproductions in the press—tend to linger, making it a distinctive trait of the Risorgimento thinker: a trait that differentiated Mazzini from his counterpart, Garibaldi, whose hands were usually given greater attention (undoubtedly an allegory of his dexterity in battle).

Even if a united Italy was, at this time, still far away, these years witnessed Lega’s pictorial apprenticeship. In the mid-nineteenth century, he attended the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence as a pupil of Pietro Benvenuti and Giuseppe Bezzuoli. Lega’s artistic development was transformed by a meeting with Luigi Mussini, who was mindful of Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres’s lessons in Rome and then moving toward a purified classicism in painting. These are, therefore, the years of the Incredulità di San Tommaso (Incredulity of St. Thomas) (fig. 9), painted in 1850 under the direction of Antonio Ciseri, Lega’s last true master. The work has Nazarene references and is distant from Lega’s mature style, but nevertheless represents the painter’s artistic debut. However, it was only at the end of the 1850s, on the eve of the campaign of the “Mille,” led by Garibaldi, that Lega began to “forget about Ciseri and do it [himself]” and started working on the four lunettes for the Church of the Madonna del Cantone in Modigliana, arriving at formal solutions decidedly more similar to the works of Francesco Hayez (233).[3] It was his 1859 meeting with the artists of the Caffè Michelangelo in Florence, however, that irreversibly influenced Lega’s painting. In the 1840s and 1850s, his style appeared perfectly in tune with the Italian masters of the first half of the century. From the early 1860s onward, however, it would be clearly oriented toward a free, almost anti-material brushstroke, tamed only at the end of the decade in his masterpiece Il canto dello stornello (The Singing of a Ditty) (fig. 10) and his portraits of illustrious figures, such as the Portrait of Giuseppe Garibaldi (fig. 11). Lega’s encounter with the Macchiaioli also allowed Lega to change the subjects of his paintings,[4] which at first concentrated on allegorical or patriotic compositions and only later on the bourgeoisie of the Tuscan countryside decorated with hand-embroidered clothes, subjects and details that a century later would inspire Luchino Visconti in the settings and photography of some of his film masterpieces (fig. 12).

The undisputed star of the exhibition was a work which lent its name to the title of the exhibition, Lega’s Gli ultimi momenti di Giuseppe Mazzini (The Last Moments of Giuseppe Mazzini) (figs. 13, 14). Begun in 1872—the year of Mazzini’s death—and finished in 1873, the painting is the final work on display; it represents the moment when the two “parallel paths” finally intersect, and the idea of Mazzini’s image begins to fade. Portrayed in the last moments of his life: wrapped in a shawl that belonged to Carlo Cattaneo and that would be passed down to Maurizio Quadrio, Mazzini appears close to death, but not without his composure and dignity; he does not give up his aura of apostle and preacher. Lega renders Mazzini’s agony as neither dramatic nor rhetorical, depriving the scene of the actual sacredness it had at the time. Immediately following his death on March 10, 1872, a crowd of patriots visited the funeral chamber established on the ground floor of Pellegrino Rosselli and Sara Nathan’s house in Pisa.[5]

The painting was exhibited at the Accademia di Belle Arti in Florence in 1873 but passed somewhat unnoticed to the point of becoming practically invisible among the public—no doubt because it was a more human and dramatic representation of Mazzini, profoundly different from the image followers had become accustomed to in the 1840s, but also because of the progressive oblivion his image fell into in the years after his death. This “misfortune”—which in reality only affected Mazzini within the Pantheon of the “fathers of the fatherland,” a memorial spiritually composed of Giuseppe Garibaldi, Camillo Benso Conte di Cavour, and Vittorio Emanuele II (the first king of Italy)—came to an end at the beginning of the twentieth century as a result of the political crisis of the Giolitti era and the exponents of the radical left being intimately linked to Masonic circles. It was mainly thanks to the latter that the first centenary of Mazzini’s birth in 1905 was marked by great events such as the introduction of the Doveri dell’uomo (Duties of Man) in 1903 as a textbook for state schools and, in 1904, royal approval for the printing of Mazzini’s works. However, the political and iconographic purgatory this man passed through after his death is well highlighted by the last room of the exhibition: an immersive space—used to simulate any public square—that highlights the history and location of the very few public monuments in Italian and international squares dedicated to the Genoese exile, from 1872 to the present day. These include the first monument to Mazzini, made in Buenos Aires by Giulio Monteverde (1874–78) on the initiative of the Italian immigrant community; the Milanese monument made a century later by Pietro Cascella (1972–74); and finally the troubled and gigantic sculptural group by the sculptor and Grand Master of Italian Freemasonry Ettore Ferrari in Rome, a work commissioned in 1902, but inaugurated only in 1949 during the post-fascist era.[6] We might consider the extent to which the figure of Mazzini has enjoyed a posthumous fame in his homeland compared to that first achieved abroad. In Italy, perceptions of Mazzini were troubled by his status as King Victor Emmanuel II’s main opponent. Abroad, Mazzini was seen as the heir to the democratic tradition of the Roman Republic. Communities of exiles and immigrants paid homage to him in public space, even obtaining monumental recognition of him on Laystall Street in London (1922)—Mazzini’s home for almost thirty years—before he was to achieve the same status in Rome.

Ultimately, L’ultimo ritratto represents an exercise in citizenship as well as a pedagogical reflection on our relationship with the past, a heritage filtered through representations in media that today may be considered secondary (e.g., monuments, relics, drawings, reproductions of prints, engravings), but that once represented a strong means of propaganda: useful for nurturing the dream of unification and then of republic, a vision that was impossible for many, regardless of how much Mazzini believed in it during his lifetime.

Notes

[1] An interesting study on the fortune and fame of the Italian fathers of the fatherland from the end of the second half of the nineteenth century until the early twentieth century was carried out in Federica Albano, Cento anni di padri della patria, 1848–1948 (Turin: Carocci 2017).

[2] Giuseppe Mazzini, La pittura moderna in Italia, ed. Andrea Tugnoli (Bologna: Editrice Club, 1993).

[3] “scordarsi di Ciseri e fare da me.” Translation by the author.

[4] On this topic, see Carlo Sisi and Fernando Mazzocca, I Macchiaioli prima dell’Impressionismo (Venice: Marsilio, 2003).

[5] For a historical reconstruction of the moments following Mazzini’s death, see Sergio Luzzatto, La mummia della repubblica: Storia di Mazzini imbalsamato (Turin: Einaudi, 2011).

[6] On monuments in Rome during the post-unification period, see Lars Berggren and Lennart Sjöstedt, L’ombra dei grandi: Monumenti e politica monumentale a Roma (1870–1895) (Rome: Artemide Edizioni, 1996).