Quo vadis?, Cabiria and the ‘Archaeologists’: Early Italian Cinema’s Appropriation of Art and Archaeology by Ivo Blom

Reviewed by Patricia SmythPatricia Smyth

University of Warwick

Email the author: patriciasmyth7[at]gmail.com

Citation: Patricia Smyth, book review of Quo vadis?, Cabiria and the ‘Archaeologists’: Early Italian Cinema’s Appropriation of Art and Archaeology by Ivo Blom, Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.15.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Ivo Blom,

Quo vadis?, Cabiria and the ‘Archaeologists’: Early Italian Cinema’s Appropriation of Art and Archaeology.

Turin: Edizioni Kaplan, 2023.

312 pp.; 138 color illus.; notes; index.

€40.00 (paperback)

ISBN: 9788899559663

In this welcome study, Ivo Blom examines the presence of nineteenth-century narrative painting in Italian early cinematic evocations of the ancient world. While primarily concerned with the intermediality of silent film, the book is also an important contribution to the recent reassessment of non-modernist nineteenth-century painting, revealing the role of artists such as Jean-Léon Gérôme, Lawrence Alma-Tadema, Georges-Antoine Rochegrosse, and Henri-Paul Motte in determining the look and feel of antiquity in films such as Enrico Guazzoni’s Quo vadis? (1913) and Giovanni Pastroni’s Cabiria (1914). As Blom notes, by the early twentieth century, the artists in question were “already out of fashion, even in official artistic circles” (9). However, what appears at first glance to be a gap between the period in which these artists were successful and their appropriation by early twentieth-century film directors is explained by the continuing circulation of their work—a “second life” as Blom puts it—as book and magazine illustrations, magic lantern slides, and stage sets.

Blom’s intensive research provides a wealth of new information on the transmedial—and transnational—circulation of images and motifs in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. The author suffers from the same problem as many of us in not knowing quite how to refer to the particular type of art with which he is concerned, offering at different points in his narrative terms such as non-modernist, bourgeois realism, and the unsatisfactory pompier (a derogatory late nineteenth-century term for history painting, alluding to French firemen’s helmets, which were thought to resemble the costumes worn by figures in these works). Although it is not Blom’s main objective, the book offers a compelling counterargument to the established art-historical narrative that dates the “death of history painting” to the end of the Second Empire.[1] His lively discussion demonstrates that this art, whatever we decide to call it, continued to matter to late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century audiences. Indeed, it still matters. Blom notes that Gérôme was an important source of inspiration for Ridley Scott’s Gladiator of 2000. Scott’s Napoleon (2023) reveals this was no flash in the pan, since it quotes Gérôme’s Bonaparte Before the Sphinx (1868), while a publicity image for the film remediates Napoleon at Fontainebleau, 31 March 1814 (1846) by Gérôme’s teacher Paul Delaroche.[2]

Blom demonstrates beyond question the importance of these artists’ work in determining the look of early film. He is also concerned with the nature of cinematic intermediality, proposing a model of “transfiguration” or “in-betweenness” for thinking about the appropriation of painting in these films, as developed in the work of Ágnes Pethö. However, this aspect of the book prompts some questions. Pethö’s theoretical framework appears to be designed to deal with the sense of fragmentation created by some types of intermediality in which the beholder is aware of the juxtaposition of different media within a single work and, by extension, of that which remains invisible: “the eerie . . . ‘other’ space between the discourses.”[3] While certain cases may fit this model, it seems less appropriate for dealing with the immersive aspect of cinema so central to Blom’s project—its capacity to “create worlds”—in the words of Scott (29).

The first chapter examines the appropriation of Gérôme’s paintings in Guazzoni’s Quo Vadis?, beginning with the most explicit borrowing, the realization of Gérôme’s Pollice Verso (1872), which shows the moment in the arena when a gladiator, having subdued his opponent, looks to the emperor, who, in a “thumbs down” gesture, seals the loser’s fate. This painting, which had already featured in a 1901 cinematic adaptation of Henryk Sienkiewicz’s novel directed by Ferdinand Zecca and as a photogravure illustration in a 1909 edition of the book, was incorporated as a static tableau in Guazzoni’s film (figs. 1, 2). References to Gérôme’s The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer (1863–83) were less explicit (fig. 3). Like Pollice Verso, this painting shows the Roman arena; however, this time a vast number of spectators are seen from such a distance that they are perceptible only as dots. In the middle distance, a group of Christians appear horribly vulnerable, huddling together as a lion emerges from a trapdoor in the foreground. The way in which this painting is incorporated into the film may at first glance seem quite different. Although elements of it are present in Guazzoni’s film, they are broken up through the process of analytical editing, prompting the question of how perceptible this reference would have been to spectators. However, as Blom discusses, publicity for the film used reproductions of both paintings, as well as publicity stills that effectively synthesized Gérôme’s compositions by joining together the significant shots to produce what Blom refers to as “synthetic ensembles” (93) (fig. 4). Blom’s argument thus rests on two tiers of intermedial visual culture: the transnational and intermedial dissemination of popular history paintings—which worked to establish a particular mental image of antiquity in the minds of spectators—and the “paratextual materials” produced as accompaniments to the film, which would, no doubt, have determined the audience’s reception of it.

This chapter also addresses the tricky question of whether, given the extent of their appropriation by film, artists such as Gérôme may be seen as “pre-cinematic” (30). The author revisits points raised in some of the essays included in the catalogue for the Musée d’Orsay’s 2010 exhibition of Gérôme’s work, The Spectacular Art of Jean-Léon Gérôme, citing the question posed by Dominique Païni as to whether the artist’s works “hold out the promise of any moving-image legacy” (96). Such arguments have been subject to charges of anachronism, with Laurent Guido and Valentine Robert countering that, by focusing on the close relationship between the paintings and publicity stills and posters, such analyses deny “the movement and the editing in cinema” (98). They contend instead that references to painting in film should be seen as a retrospective tendency in the later medium rather than a “prefiguration” in the earlier one.[4]

The main bone of contention seems to concern how far a static medium like painting can be thought to have anticipated the mobile gaze and temporality of cinema. Paintings such as The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer have been the particular focus of such discussions, because, as Marc Gotlieb has argued, their expanded narrative suggests a kinship with cinema. Having seen the lion emerge from the trapdoor, we cannot help but imagine the horrors to come; the darkening sky and the tracks in the sand of the arena left by chariot races tell us that this final spectacle comes at the end of a long day of intense emotion, while, behind the group of martyrs, the human “torches”—tied to stakes and smeared with pitch—are at various stages of conflagration.[5] Moreover, the manner in which certain parts of the scene, such as the lion and tiger that have yet to emerge from the trap, are known only to the viewer of the painting and not to the participants in the action suggests, Gotlieb argues, the “omniscient spectator” of the cinematic medium (98).[6] Blom also cites Païni’s argument that the tendency of artists such as Gérôme to portray the “moments after the key events” creates effects that are analogous to those of cinematic temporality (96, emphasis in original). As he writes, paintings such as Gérôme’s Death of Caesar (1859–67), in which the body of the assassinated victim lies abandoned in the foreground as jubilant senators rush from the theater of Pompey in the background, suggests a “tracking-out shot.” With the human figures reduced to relatively minor components within a larger composition, the painting creates, it has been argued, “a feeling of ordinariness,” that aligns it with cinema (96).

To resolve this conundrum, Blom invokes Catherine Russell’s discussion of “parallax historiography,” a term used to describe the phenomenon whereby our present perspective on a given historical event or practice reveals some aspect of its nature, which, although certainly there, may not have been possible to articulate at the time. However, I am not convinced that a concept such as parallax historiography is required since, as Blom notes, Gérôme’s paintings were understood in their own time to have been expressly designed for circulation in a range of media (96). Prior to the advent of film, that range included temporal forms such as theatrical performance and dioramas. Moreover, the nineteenth-century practice of producing so-called variations of well-known pictures that presented the same figures in “close-up,” at different points in time, or from different perspectives, created the sense of a mobile spectator, long before film.[7] Whether or not Gérôme’s temporality is specifically “cinematic” in nature remains open to discussion.

Chapter 2 deals with the importance of Alma-Tadema’s paintings of the classical world for Quo Vadis?. Although Alma-Tadema’s influence on film has been much discussed, his appeal to early cinematographers is more difficult to explain than that of Gérôme. Unlike the paintings by the French artist, Alma-Tadema’s work is notable for its relative stasis and light emotional register (with notable exceptions such as, for example, The Roses of Heliogabalus [1888]). Moreover, much of the fascination that his work continues to exert lies in its startlingly realistic effects of color and texture, qualities that are, of course, either absent or somewhat diminished in early film. However, Blom discusses the ways in which the deep perspectives of Alma-Tadema’s paintings determined the spatiality of the new medium, while the divisions within them may be related to the “internal editing” (i.e., the compartmentalizing of different spaces within the shot) of their cinematic counterparts. Blom further explores the archaeological research that underpinned both this artist’s paintings and his work for the theater in the 1880s and 1890s, which, Blom argues, contributed to “the persistence of his work in public memory” (107).

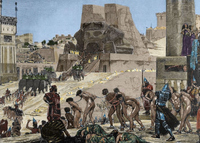

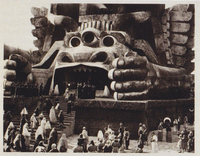

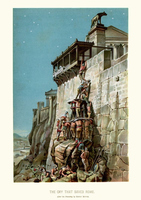

Chapter 3 considers Cabiria, Pastrone’s epic of ancient Carthage set during the Second Punic War. Blom traces the influence of literary, theatrical, and artistic evocations in the creation of Pastrone’s orientalist fantasy, noting in particular the presence of nineteenth-century visualizations of the femme fatale—such as Alexandre Cabanel’s Cleopatra (1887) and Edmund Dulac’s representation of Circe in The Enchantress (1911)—in the portrayal of Sophonisba, the Carthaginian queen central to Pastrone’s story (fig. 5). Blom identifies the work of Gérôme’s pupil Henri-Paul Motte as a source, specifically, his Baal Moloch Devouring Prisoners of War in Babylon (1876). Reproductions after Motte’s paintings are shown to have circulated extensively. Indeed, his image of the sinister anamorphic temple into the jaws of which a line of human victims disappears is present not only in Cabiria, but also in an advertisement for meat extract; it was also arguably the source for Fritz Lang’s factory imagery in Metropolis (figs. 6, 7). Motte’s The Sacred Geese of the Capitol (1881) provides the source for the scene in Cabiria in which the Roman troops form a living ladder to scale the walls of the city of Cirta (figs. 8, 9). As Blom notes, the situation is reversed in Pastrone’s film since in Motte’s composition it is the ingenuity of the Gauls attacking the Romans that is pictured; however, this speaks to the dual quality of certain nineteenth-century motifs that combined memorability with a tendency to become untethered from their original referent in the mind of the spectator.

As Blom writes, Rochegrosse’s illustrations for Flaubert’s Salammbô (1862) emerge as the dominant influence on Pastrone’s vision of ancient Carthage. Flaubert is known to have opposed illustrated editions of his work; yet, as Blom shows, his evocative prose had an unanticipated second (and third) life thanks to these realizations. In this chapter, as in the others, Blom invokes Pethö’s concept of transfiguration, itself drawn from the work of the Dutch scholar Henk Oosterling, to explain the nature and effects of the intermediality of these films. The appropriation of Rochegrosse’s work in Cabiria, Blom writes, “fits Pethö’s ideas on mediality and transfiguration” (210), since, according to Pethö’s formulation, “‘each medium participates with its own cognitive specificities, shaping the messages conveyed by the cinematic flow of images,’ while simultaneously being ‘a figure of “in-betweenness” that reflects on both media involved in this process’” (210). In Blom’s account, this model suggests an increased awareness of mediation on the part of the beholder as they perceive not only the presence of one media inside the other, but also that which remains unrepresented and unseen: the space between them. This is therefore a self-reflexive conception of intermediality in which the beholder is aware of the differences between diverse media and the fissures separating them. As Blom writes, the inclusion of tableaux vivants within films—such as the “short static, almost photographic, insert” of Gérôme’s Pollice Verso in Quo vadis?—creates “an odd kind of friction within the film” (88, 31).

In the case of such “freeze-frames” that interrupt the narrative flow, this may be the case; however, Blom does not discuss the nineteenth-century term for the practice of absorbing paintings or prints into a temporal drama: realization. In contrast to the “friction” and resulting awareness of mediation that Blom describes, Martin Meisel’s classic interdisciplinary account of this practice, Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England, explores the fluidity with which compositions and motifs circulated among nineteenth-century media. As Meisel writes, realization was the “re-creation and translation into a more real, that is more vivid, visual, physically present medium.”[8] As I and others have argued, the scaling up in three dimensions of a given image, with live actors in place of painted figures, is comparable to the modern practice of remediation as discussed by Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin in their work on new media.[9] In their account, each new media absorbs features of the previous one, while at the same time claiming to improve upon it, presenting the viewer with what seems to be a more direct encounter with the scene portrayed. Thus, film remediates photography, while virtual reality remediates film. But the circulatory model that both Meisel’s account and Bolter and Grusin’s concept of remediation suggest does not account for the complexity of nineteenth-century visual culture. While painting was certainly remediated in the more palpably solid three-dimensional medium of theatre, compositions were also absorbed into other paintings or two-dimensional media such as print and photography. However, the objective was still immediacy. The facility with which compositions were transposed from one form to another suggested the effacement of all barriers and thus a direct unmediated encounter with the thing portrayed, while multiple iterations of a given image each served to validate the authenticity claims of the others. This is quite different from Blom’s account in which the beholder is more, rather than less, conscious of mediation. It would therefore be interesting to know how Blom considers his own account in relation to these models, especially since he cites the many instances in which paintings by Gérôme, Alma-Tadema, and others were realized in theatrical performances as an intermediary stage that, along with printed reproductions and magic lantern slides, bridged the gap between the period in which these artists were practicing and the time of their appropriation by early film (52–53).

Throughout the book, Blom refers to the “in-between,” by which he means this very culture of replication: “the migration and multiplication of pictorial images before they appear in films, thus book and magazine illustrations, slides, stage sets, etc., but also paratextual materials simultaneously accompanying the films such as posters, postcards, and advertisements” (23), in other words, the familiar images that combine to form the mental picture of the classical world in the mind of the beholder. To return to the appropriation of Gérôme’s The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer in Quo vadis?, Blom states in reference to that example that “we are basically talking about a third medium, a tertium comparationis” (105). This idea of a “third medium” or “in-between” stage is particularly crucial here, since the painting is not realized as a tableau in the film, but is, rather, embedded within a narrative made up of edited shots and directly cited only in the publicity poster. His reference to a tertium comparationis suggests an overlap or point of similarity between two different things, but perhaps the third thing is more akin to a “master copy” in the mind’s eye of the spectator. Blom hints at this throughout his book, but when he asks, in reference to the poster featuring The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer, “Is that still the in-betweenness Pethö discusses?” (105), my feeling is that Pethö’s self-reflexive model of intermediality is perhaps not the best fit for the spectator’s vividly imagined interior world.

The final chapter takes a different direction to that of the previous three in that it considers the role of archaeology in Pastrone’s vision for Cabiria. The idea of these films as immersive environments runs through Blom’s entire study—in the first chapter, he quotes Scott—“I love to create worlds”—on agreeing to direct the film Gladiator after having been shown a reproduction of Gérôme’s Pollice Verso (29). However, this theme is most dominant in this last section of the book. As Blom relates, the relative dearth of archaeological knowledge at the time allowed for the free play of fantasy in the way that ancient Carthage was evoked on film. Pastrone, we are told, mined collections in the Louvre and the Museo Egizio (the Egyptian museum in Turin), but altered and rearranged objects and elements, often changing their functions for his film (241). The popular perception of Carthage as a hybrid culture that combined elements of Greek, Egyptian, and Assyrian art, enabled the director to invent an eclectic, yet extremely coherent, composite style. His version of Punic antiquity was an orientalist fantasy. Drawing on contemporary associations of Egyptian and Assyrian culture with the exotic, Pastone’s Carthage struck a contrast with the more familiar iconography of ancient Rome, as presented in the film. In painting, the contrast between east and west would have been amplified through bright or jarring color. In Pastrone’s film, of course, this was not possible, but stills from it demonstrate the vivid patterning and odd shapes—Blom draws our attention to the repeated motifs of checkers, triangles, and lozenge shapes—that combine to create a sense of visual excess, luxury, and strangeness in the monochrome medium (fig. 10).

Blom makes a powerful case for the continued legacy of the artists he writes about. He quotes Vern G. Swanson, who in his 1977 account of Alma-Tadema writes that the artist’s “influence on other painters was not great, for he took few pupils, and has never been regarded as an innovator” (110). Blom rightly challenges a model of artistic significance that is so clearly skewed in favor of modernism and offers an important alternative framework for understanding the visual culture of this period. Referring to Scott’s Gladiator, he writes that “the public memory of Gérôme around 2000 was much smaller than in 1913” (101). This may be, but Gérôme’s legacy arguably persists in our mental image of antiquity to this day, whether we are conscious of it or not.

Notes

[1] Patricia Mainardi, The End of the Salon: Art and the State in the Early Third Republic (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 3.

[2] Thank you to Emma Sutcliffe, University of Burgundy, for drawing my attention to this.

[3] Ursula Link-Heer and Voker Roloff, as cited in Henk Oosterling, “Sens(a)ble Intermediality and Interesse: Towards an Ontology of the In-Between,” Intermédialités 1 (Spring 2003): 38, https://doi.org/10.7202/1005443ar.

[4] Laurent Guido and Valentine Robert, “Jean-Léon Gérôme: Un peintre d’histoire presume ‘cineaste’,” 1895. Mille huit cent quatre-vingt-quinze 63 (2011): 8–23, https://doi.org/10.4000/1895.4322.

[5] Marc Gotlieb, “Gérôme’s Cinematic Imagination,” in Reconsidering Gérôme, eds. Scott Allan and Mary Morton (Los Angeles: Getty Publications, 2010), 54–64.

[6] On the “omniscient spectator,” see Gotlieb, “Gérôme’s Cinematic Imagination,” 62.

[7] Patricia Smyth, Paul Delaroche: Painting and Popular Spectacle (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2022).

[8] Martin Meisel, Realizations: Narrative, Pictorial, and Theatrical Arts in Nineteenth-Century England (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1983), 30.

[9] Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin, Remediation: Understanding New Media (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999). See also Caroline Radcliffe, “Remediation and Immediacy in the Theatre of Sensation,” Nineteenth Century Theatre and Film 36, no. 2 (2012): 38–52, https://doi.org/10.7227/NCTF.36.2. Radcliffe applies Bolter and Grusin’s framework to nineteenth-century melodrama.