American Art History Digitallysponsored by the Terra Foundation for American ArtA Measure of Success: An African American Photograph Album from Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Connecticut

by Laura Coyle, with Mirasol Estrada and Allan McLeod

Laura Coyle is assistant director for cataloguing and digitization at the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture, where she is coeditor with Michèle Gates Moresi of the photography book series Double Exposure. Before joining the Smithsonian, she was curator of European art at the Corcoran Gallery of Art. She earned a PhD in art history from Princeton University, an MA in art history from Williams College, and a BA from Georgetown University. Her research specialties include modern and contemporary art, the history of photography, and the history of still-life painting.

Email the author: coylel[at]si.edu

Citation: Laura Coyle, with Mirasol Estrada and Allan McLeod, “A Measure of Success: An African American Photograph Album from Turn-of-the-Twentieth-Century Connecticut,” Nineteenth-Century Art Worldwide 23, no. 2 (Autumn 2024), https://doi.org/10.29411/ncaw.2024.23.2.24.

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License  unless otherwise noted.

unless otherwise noted.

Your browser will either open the file, download it to a folder, or display a dialog with options.

Scholarly Article|Interactive Feature|Conservation|Project Narrative

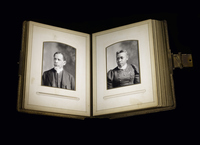

Despite its broken spine and other signs of devoted use, this photograph album of African American portraits from the Smithsonian National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC) kept the thirty photographs inside in good condition for more than one hundred years (figs. 1, 2).[1] The album’s early provenance is unknown, but its association with Connecticut is strong. More than half the photographs were taken in commercial photography studios in New Haven or Waterbury, Connecticut, and all the people identified in the album have a connection to one or both cities. A small, pink, printed label for J. H. McKinnon & Co., a stationer, printer, and book manufacturer in Waterbury, is pasted on the inside of the front cover (fig. 3). Between 1884 and 1891, J. H. McKinnon had a shop on 85 Bank Street in downtown Waterbury, where the album was purchased.[2] Based on what is known about the photography studios, the sitters, and the sitters’ clothing, the photographs date from the mid-1880s to about 1910.

This album enacts the idea of Frederick Douglass (1818–95) that photographs of African Americans reveal the truth, showing Black people as they really are, not the way others assume them to be or the way they are represented in racist images.[3] In Douglass’s view, photographs of African Americans can narrow the gap between what they deserve as a people and how they are treated by the world around them.[4] This study demonstrates how the African Americans pictured in the album used photography to construct images of racial uplift, as theorized by scholars such as Deborah Willis.[5] It illuminates how the sitters capitalized on dress and portrait conventions to project middle-class status and convey excellent character. This study also shows how the compiler used the album to create a composite image of Black respectability and community grounded in family, friends, and church, a way of life prized by those it represented. These photographs fit into a long tradition of African American commercial portrait photographs, which began as soon as photography studios appeared in the United States and lasted for more than a century.[6] Often dismissed by photography historians as conventional and lacking in creativity, commercial photographic portraits can be, as Brian Piper argues, “typical and spectacular at the same time.”[7] The conventions of commercial portrait photographs provide a basis for comparison that allow for generalizations about the genre, but these photographs are also spectacular because of their realism and variation—each one clearly represents an individual.

Studio photographs like those in the album also helped African American sitters and viewers imagine and even achieve a better life for themselves. Coinciding with the compilation of the album, W. E. B. Du Bois (1868–1963) writes about the responsibilities of African Americans, contending that respectability, such as that cultivated by the sitters and represented in their photographs, was essential to the economic and social progress of Black individuals, families, and communities.[8] At the same time, adults associated with the album probably understood how fragile this progress could be. Tales about gains and losses, about where people in the album came from and what they were like, and about who they were at the time the photographs were taken and what happened to them thereafter are the types of stories that the family who owned the album surely told as they paged through it. Most museums and archives have not gone out of their way to collect photograph albums of unidentified people, especially African Americans, but the NMAAHC was eager to accept this album as part of its commitment to representing people who are and have been consistently overlooked. Reviving narratives associated with the album, to the extent possible, provides a more nuanced interpretation of the successes, challenges, and varieties of Black life and its representation in the United States around the turn of the twentieth century. As Mary Trent notes, family albums in museums and archives “introduce records that otherwise would fall through the cracks of recorded history.”[9]

The album measures 10 ½ x 8 x 3 inches, about the size of a modest family Bible, which was the inspiration for the form.[10] Originally the cover was wrapped with textured brown leather or a leatherlike material. By the time the museum received the album in 2009, the covering was badly tattered, exposing much of the padded, linen-wrapped support for the cover underneath. The front of the title page is printed in green and white with gilt highlights (fig. 4). The design features an arch decorated with flowers and a scroll that displays the word “album” in gold capital letters. In comparison with other albums from the period, this one was modest; mail order catalogues carried albums in a wide range of prices, and many had much fancier outer covers and decorations.[11]

Whatever its cost, the album’s relatively understated design seems appropriate for the fashionably but not ostentatiously dressed people in the photographs. Most of the photographs are cabinet cards; they represent cherubic babies, stylish young women, dapper young men, compliant children, a respected minister and his wife, a well-known bishop, and a few older gentlemen. In addition to the photographs, the album includes photographs reproduced as halftone prints and a card memorializing the passing of a woman named Susan Bell, dated March 5, 1894. Albums with or without such memorial cards are reminders of the cycle of life and the passage of time, with family and friends represented in different life stages. Their images are records of the past that help to anchor memories.

The People in the Album

The people in the album photographs represent a span of generations, from those with firsthand memories, if not firsthand experience, of slavery to those born thirty-five or so years after the end of the Civil War, at the dawn of a new century. When the photograph album arrived at the NMAAHC, the names of most of the portraits’ subjects were unknown. Now, six people in the album are identified: Bishop James W. Hood (1831–1918); Rev. G. H. S. (George Henry Service) Bell (1838–1911) and his wife, Susan Bell (1836–94); Ida Allston (1872–between 1930 and 1948); Mary Evelina Allston (1888–1975); and Izetta Alexander (ca. 1861–1936) (figs. 5–10). In the Interactive Feature, stories about the people in the album are shared alongside the photographs, but it is useful to get to know here the sitters and their families as a group, focusing on the period of the photographs and the places that connect the identified sitters and their families.

Just as women were the traditional keepers of the home, so the compilers and keepers of family albums were almost always female.[12] The Interactive Feature allows readers to page through the album at their leisure, in the same order the photographs appeared when the album came to the museum, starting with images of babies, enveloped in billowing christening gowns (figs. 11, 12). Whether the order of the photographs has remained unchanged is not known, but if the sequence created by the original owner has been preserved, presenting the youngest subjects first was an inversion of customary family hierarchy. Society at the time privileged adults, and among adults, men. This hierarchy, however, applied most often in the public sphere; while a man was usually considered the head of the family, affairs at home were traditionally the domain of women, who bore the children and, unless the family was wealthy, nurtured and raised the demanding newcomers. If the photographs are still in their original order, placing the images of the infants first signifies their importance to the album compiler and may have been an act of resistance to the male-dominated world outside the home.

Even if the album photographs are not in their original order, aside from their sequence, together they have a leveling effect: each page in the album is equal to every other page, no matter who is represented. Access to fashionable but inexpensive clothing allowed even sitters of modest means to shine. The adult sitters capitalized on widely held assumptions of the time that fashionable clothing, careful grooming, a sober expression, and a stately pose, captured in a proper setting, projected middle-class values, such as propriety, accomplishment, refinement, learnedness, and integrity.[13]

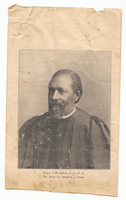

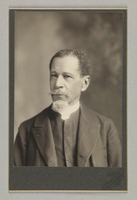

The most prominent person in the NMAAHC album is Bishop Hood (see fig. 5).[14] Hood was born free in Pennsylvania, the son of a Methodist minister. In 1855, he moved to New Haven, Connecticut, where he worked as a waiter at the Torentine Hotel.[15] The next year, he secured a license to preach and gave his “trial sermon” at New Haven’s Varick Memorial A.M.E. Zion Church, where he is remembered as one of the most powerful preachers in the church’s history.[16] After a few years in New Haven, he was appointed as an unpaid missionary to Nova Scotia; he was ordained as an elder in Hartford, Connecticut; and he served in Bridgeport, Connecticut, for half a year in 1863, before moving to North Carolina, where he lived for the rest of his life. He helped establish Zion Wesley Institute (now Livingstone College) in Salisbury, North Carolina; he presided over the North Carolina Freedmen’s Convention in 1865; he participated in the state constitutional convention and the Republican national convention in 1872; and he served as an assistant superintendent of the North Carolina Freedmen’s Bureau.[17]

The compiler of the album may have included Hood because she knew him or simply because she held him in high regard. While this is a family album, albums of this type in the nineteenth century often included photographs of friends and people the compiler admired as well as kin.[18] In his bust portrait, probably taken in 1894, Bishop Hood is posed formally, in three-quarter profile, wearing his pleated clerical robe, which identifies him as a man of the cloth. His portrait supports a description of him as a man who “wears his dignity with great ease and is one of the most fatherly Bishops of the age.”[19]

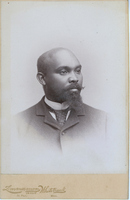

Bishop Hood authored a history of the A.M.E. Zion Church that includes a biography of Rev. George Henry Service Bell, who went by G. H. S. Bell (see fig. 6).[20] Bell was born free in Bermuda to parents who had recently been emancipated. He married Susan (see fig. 7) in Bermuda, where they had their only child, Samuel Bell, born in about 1858.[21] G. H. S. Bell owned his own business in Hamilton, Bermuda, then taught in a government school for fifteen years before studying for the Episcopal ministry. Hood writes in his church history that in about 1856, Bell “became interested in the subject of colored churches and their ministry . . . [which] rekindled his childhood ambition to be a ‘preacher of the Gospel.’”[22] He was granted a local preacher’s license in 1872. In April 1880, Bell traveled to the United States and visited the A.M.E. Zion Conference in New Haven, where he applied for membership, was accepted, and was sent to serve in Cambridge, Massachusetts, the first of many New England cities to which he would be appointed. He probably served in Waterbury from 1892 to 1894 and again from 1896 to 1900.[23] By 1902, he was serving as presiding elder of the New England Conference.[24] It seems likely that the compiler of the album’s photographs was acquainted with the Bells, because the inclusion of Susan Bell’s memorial card in the album suggests she attended the service. Rev. Bell remarried in 1895, and was living in Hartford with his wife Mary when he died in 1911.[25]

In his biographical sketch of Bell, Hood writes:

Brother Bell is a man of high Christian character and greatly loved by his people. During the long period that he has held the position of Conference steward his accounts have been well kept, and not a cent has gone astray, and the expense of running the office has been exceptionally and surprisingly small. We venture the assertion that no living man is more straightforward or trusty in his dealings.[26]

For their portraits, taken in early 1894 while the Bells were assigned to Waterbury, Rev. and Susan Bell dressed soberly and appropriately for their roles in the community as pastoral leader and pastor’s wife.[27] Bell’s close-cropped hair is still mostly dark, but his walrus mustache and beard are nearly white. He wears a coat over a waistcoat with a notch at the top of its placket that highlights his bright white clerical collar. A cord or chain across his chest is perhaps attached to eyeglasses hidden in his waistcoat pocket. He looks dignified and trustworthy, reinforcing his reputation as a careful yet approachable steward. Mrs. Bell looks thoughtful and serious. She wears spectacles, which may have signaled at the time that she was literate and educated.[28] Her dark dress with a ribbed pattern has a snug bodice decorated with orderly rows of covered buttons; around her neck she also wears a white collar, for the sake of fashion rather than the dictates of the Church. The leg-of-mutton sleeves of her dress are also stylish, puffed around her upper arm and tight below the elbow. Her hair is pulled back tightly at the sides, with bangs that are clipped back. Her gold watch chain is pinned to her collar; one length of the chain is weighted and decorated with fobs while the other dips across her chest, then tucks into her bodice, locating her pocket watch out of sight and harm’s way. She passed away within weeks or days of this photograph and may have been unwell, perhaps explaining why she looks so somber.

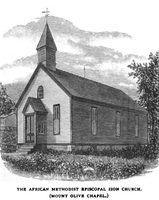

Well educated and well respected, Rev. Bell likely held an elevated place in Waterbury’s social hierarchy, although many elite African Americans at the time belonged to the Episcopal or Congregational Church.[29] Nonetheless, Mount Olive A.M.E. Zion Church was the city’s first Black church—and the only Black church until 1900.[30] Mount Olive is still active and may be the oldest continually operating Black institution in Waterbury.

Fundraising for Mount Olive church at a site on Pearl Street began in 1883, when between only 133 and 171 African Americans lived in Waterbury (fig. 13).[31] By 1891, the church was “renovating, refitting, painting, papering, and building an addition at a cost of $869.69.”[32] Rev. Bell was serving elsewhere when the Southern Section of the New England Conference convened at Mount Olive A.M.E. Zion Church in 1906, but he likely attended as treasurer of the conference.[33] Along with services, Sunday school, and other religious instruction, Mount Olive hosted many social events, such as concerts, lectures, and meetings of the J. C. Price Historical and Literary Society.[34] During the period of the album’s compilation, Mount Olive was the heart of Waterbury’s African American community.

The members of Mount Olive probably joined other Black churches in the area for frequent picnics, such as the ecumenical Union Excursion in 1890 that attracted one thousand people to High Rock Grove, a setting with “romantic and weird-like scenery” in Naugatuck, a town adjacent to Waterbury.[35] The organizers also invited the members of the African American lodges and other associations in New Haven, Waterbury, and other nearby cities.[36] Membership and leadership in Black churches often overlapped with membership in Black fraternal societies such as the Prince Hall Masons and Grand United Order of Odd Fellows of America as well as their sister organizations, Order of the Eastern Star and Grand Household of Ruth.[37] Bishop Hood was a Mason, and while pastor at New Haven was instrumental in establishing Connecticut’s Masonic lodges.[38] Rev. Bell was also a Mason.[39] African American Churches, fraternal and sororal organizations, and other clubs and societies provided social and service opportunities for African Americans who were denied admittance to white-run organizations, and helped them to build professional and social networks and leadership skills. Out-of-town events like church picnics and balls encouraged the small Black populations in Connecticut cities and towns to engage in and create ties within a more expansive African American community.

In addition to Bishop Hood and the Bells, Ida Allston is firmly identified in the album (see fig. 8). Ida was well-known enough that she appeared in stories about Waterbury society in one of New York’s African American newspapers, New York Age. The paper reported in January 1891 that “Miss Ida Allston of New Haven is visiting her sister here [in Waterbury], Mrs. F. M. Robinson,” whose first name was Sarah.[40] Ida was probably born in Philadelphia, married Richard W. Brown (1869–1919) in about 1893, and lived with her family in New Haven until about 1921 or so.[41] In the US census of 1900, Richard’s occupation is listed as locksmith.[42] A decade later he is listed as a machinist who owned his own home, working at Sargent & Company in New Haven, one of the city’s major hardware manufacturers.[43] Maybe Richard is the well-dressed man with two pins adorning his necktie, one a gem and the other decorated with a key on a scroll (fig. 14). This photograph, probably taken between 1890 and about 1900, shows an intently focused man, neatly attired in a coat with trimmed lapels and a matching waistcoat. His shirt with folded collar points is perfectly pressed and sets off a wide, knotted tie. The hair on his balding head is combed down, a contrast to his wiry sideburns and generous moustache. He comes across as serious, proper, tidy, and intentional.

When Richard died in 1918, Ida became a widow, with five children between the ages of about eight and twenty-four years old. She was listed as head of her household in 1920, working as a nurse. She still owned the home inherited from her husband, next door to her parents, and was living with three of her children.[44] In 1923, Ida married Daniel Scott (1856–1948) in New Haven; by 1925, they were living in New York City with her two youngest children.[45] Ida died sometime between the time when the US census was conducted in 1930, and 1948.[46]

Ida, of course, had no idea that all this would happen in her life when she posed for her portrait between 1888 and 1891. At that time, she was between sixteen and nineteen years old. Despite her grown-up hairstyle, dress, collar, and drop earrings, she still seems very young, with the chubby cheeks of a child. Her hair is parted on the side and pulled back, with heavy bangs on her forehead. This was the current style, but the bangs must have been a challenge for young women such as Ida, with curly hair. The bodice of her dress looks relatively plain, in a solid color pleated down the front, but it is dressed up with a detachable, starched, ruffled-lace collar that seems to have a life of its own. Her head is turned slightly to the right, she seems to suppress a smile, and her eyes are lively and bright. She presents herself as fashionable but proper, and at ease with herself and the world.

Ida’s sister, Mary Evelina Allston, is one of the infants pictured in the album (see fig. 9). Looking none too happy about being photographed, Mary Evelina is propped up on a chair covered with an embroidered blanket, setting off her long, billowing christening gown. Her wavy hair is smoothed down, and she wears a chain around her neck. As the abundance of baby pictures that survive from around the turn of the twentieth century attest, an addition to the family was something to celebrate and visually commemorate, an event worth the effort of dressing a baby in a fresh, snow-white gown; traveling to the studio; perhaps making a climb up the stairs to the top-floor, babe in arms; and risking a mess or a meltdown, all for a set of twelve cabinet cards, one or two to keep and the rest to give away.[47] Many babies did not survive their first year of life, and until emancipation, many African American families could not count on staying together. The birth of a healthy, Black baby, like Mary Evelina, who would remain with her family until she was an adult, was not to be taken for granted. Particularly for African Americans in this period, an air of poignancy hovers over baby photographs.

Going by a bewildering variety of first names vexing to amateur genealogists—Mary, Evelina, Evelyn, Evalinia, and Mary Evalina—Mary Evelina was the youngest of Ida’s five siblings, born while the family lived in New Haven.[48] When she was eight years old, Mary Evelina is mentioned in a Black-owned newspaper in Virginia, the Richmond Planet, in an account that adds texture and humanity to the official records about her and her family:

A pretty home wedding was performed by Rev. W. H. Coffin, D.D., on the evening of March 3rd [1897], at the residence of Mr. and Mrs. James Allston, 133 Butler St. The contracting parties being Miss Rebecca Lauretta Allston and Mr. Henry Scroggins, both of this city.

The bride was attired in a pretty gown of cream colored crepon with lace trimmings. The floral ornaments were white carnations. The groom wore the conventional evening dress suit.

The bride was given away by her father. Little Evelina [Mary Evelina Allston], sister of the bride, was flower girl, with the bride’s little nieces, Ethel [Ethel Isabella Robinson (b. 1893)] and Beatrice Robinson [Florence Beatrice Robinson (1896–1979)], the attending maids.

Beside the family, which is a very large one, including Mr. and Mrs. F. M. Robinson, of Waterbury, Conn., there were present Mrs. S. Pheonix [sic] and daughter, the latter presided at the piano and rendered several beautiful selections, after which all enjoyed refreshments and a grand social evening. Mr. and Mrs. Scroggins are enjoying the congratulations of legations of friends.

The happy couple will reside at 133 Butler Street for the present.[49]

One of the intriguing things about this notice is that a wedding in New Haven made the front page of a newspaper in Richmond, Virginia. Connecticut did not have an African American newspaper, and during this period stories like this one about African American families in a white-owned newspaper in Connecticut were rare. Consequently, African American correspondents around the state sent notices about Connecticut social events to a variety of out-of-state, Black-owned newspapers, which had subscribers all over the country. Perhaps the Allstons had friends or relatives in Richmond, but even so, other readers must have enjoyed these stories as examples of racial progress, prosperity, and uplift, even if they did not know the people involved.

By 1920, Mary Evelina was lodging in New York City with her brother James, a hotel cook, and Joseph Da Costa (1880–between 1942 and 1950), a sexton at a church. Joseph was born in Saint Kitts, in the British West Indies, to an English father and a Portuguese mother.[50] He arrived in New York by way of Hamilton, Bermuda, in 1903. In 1921, he and Mary Evelina married.[51] By 1929 they had two children, Rosalie Regina and Joseph.[52] They lived in New York City. Joseph Sr. petitioned for naturalization several times, but it is not certain that he obtained citizenship by the time he died, sometime between 1942 and 1950.[53] The only known photograph of him is clipped to one of these sets of naturalization papers. In the US census of 1940, Mary Evelina is listed as a pianist for a theater.[54] She later lived with her son and died in Brooklyn in October 1975.[55]

One of the women among the unidentified cabinet-card photographs (fig. 15) may be another Allston sibling, Sarah Allston (1870–1949), the older sister—“Mrs. F. M. Robinson”—that Ida visited in Waterbury. Dressed and posed similarly and photographed in the same studio as Ida, she strongly resembles her, with the same-shape face, large, wide-set eyes, strong eyebrows, and a similar nose and mouth. Like Ida, she wears her hair up, with curly bangs, and her solid-color dress is gussied up with a lace collar, though her collar is black. The bodice of her dress is also more intricate, with pleats and lapels, and the sleeves are significantly puffed at the shoulders, a style that came into fashion in the early 1890s. Although posed like Ida, with her head turned to her right, she has a completely different bearing. Clearly older than Ida, she appears more mature and confident, with a no-nonsense demeanor. She would need this fortitude, as she gave birth to ten children between 1890 and 1913 and raised eight to adulthood.

Sarah was born in Philadelphia in 1870 and moved with her parents and siblings Ida, Rebecca Lauretta, and James to New Haven by 1881. In about 1888, around the time the photograph in the album was taken, she married Foster Marshall Robinson (ca. 1860–1920). Born in South Carolina, he was in New Haven working as a blacksmith in 1887 and as a waiter in 1888.[56] Foster belonged to the Widow’s Son Lodge 1, Free and Accepted Masons, in New Haven.[57] Not long after he and Sarah moved to Waterbury, he was in business for himself as a truckman.[58] Their first child, Emma Elvira, was born in 1889.[59] A few years later, the family was living on Pearl Street across the street from Mount Olive Church; the barn Foster rented for his business was on the same site.[60] In 1895, catastrophe struck:

An alarm of fire was rung at 2:30 this morning . . . and soon the noise of the big gong . . . could be heard all over the city. The fire was discovered in a barn belonging to Francis De Bussy, 75 Pearl Street, which was used by F. M. Robinson, a colored man, and contained a valuable horse, carriage, express wagon, a quantity of hay and other things, all of which, with the building, were totally destroyed, the horse also perishing in the flames. The loss is estimated at $300. Robinson had no insurance on his property. The noise of the horse awakened several of the neighbors, and great efforts were made to save the animal, but when assistance arrived, it was too late to do anything, for the whole building was enveloped in flames. There is no clue to the origin of the fire but it is believed to have been the work of an incendiary.[61]

Somehow, Foster recovered. He listed his business in the Waterbury and Naugatuck Directory, in which the editions from 1899 through 1906 included a paid advertisement.[62]

In addition to being neighbors to Mount Olive A.M.E. Zion Church, Foster and Sarah were among its active members.[63] Perhaps some of the babies or children in the album who were photographed in Waterbury are Robinsons who were christened there. Foster and Sarah lived in Waterbury until 1907, when they moved with their children to Becket, Massachusetts, where they bought a farm.[64] Mount Olive held a farewell reception in honor of Foster and his family.[65]

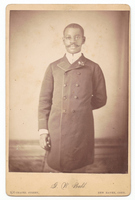

Perhaps Foster is the solemn young man in a long, double-breasted coat, a sprig of flowers placed in a buttonhole, pictured in one of the album’s photographs (fig. 16). He stands with one hand behind his back, a common pose, and holds a walking stick in his other hand. The date of the photograph, gleaned from records about the studio, coincides with the year he and Sarah married. The photographer lightened the area under his chin, a technique frequently used to define the faces of people with dark complexions. Someone later embellished the sitter’s neatly trimmed moustache and his stand-up collar. He projects quiet confidence and a sense that he is prepared for whatever life sends his way.

Given Foster’s trade, he also could be the man with the horseshoe stickpin in the photograph taken around 1890 (fig. 17). The name Sarah Robinson, Foster’s wife, appears on the back of this picture. The cabinet-card photograph was taken in Philadelphia, however, and the man appears much older than Foster would have been in the 1890s, so it seems more likely that the photograph is of Sarah’s maternal grandfather who lived in Philadelphia, William H. Crawford (ca. 1823–90). A lucky horseshoe would have had special meaning to him, because he was employed as a driver and messenger.[66] Dressed neatly in a heavy, double-breasted coat, white shirt, and patterned tie, he looks a bit weary, yet dignified and solid. Carefully groomed, he presents as a man who is proud of what he had achieved over a long life.

As the New Haven newspaper noted, Ida, Mary Evelina, and Sarah grew up in a large family, which was headed by James Allston (1843–1911) and Anna Crawford Allston (1848–after 1910).[67] James was born in North Carolina. Anna, born in Georgia, had moved with her parents and her younger siblings to Philadelphia by about 1854.[68] James and Anna married in about 1869 and lived in Philadelphia before moving to Connecticut with their four children.[69]

James worked as a cook, as a janitor for Yale University, and as a chef at St. Margaret’s Episcopal School for Girls, a boarding school in Waterbury.[70] In 1900 he opened a restaurant in Waterbury with resident Mack Jones.[71] Although the restaurant did not last, for several summers James was a popular cook at a Y.M.C.A. camp on Tuxis Island, near New Haven, “doing a great deal in the way of improving the camp” and entertaining the boys by singing spirituals.[72] And he could dance! In 1901, he entered a cakewalk contest held in an open-air theater in Forest Park in Waterbury, where a report notes “there promises to be some lively stepping among the contestants for that first [cash] prize.”[73]

By 1910, James and Anna Allston had separated; for many African Americans, emancipation brought not only the legal right to marry but also the right to divorce. Anna moved to New York City, where she lived with her widowed mother and worked as a nurse.[74] James lived in various places, including Waterbury and Becket, with his daughter Sarah and son-in-law Foster.[75]

James could be the man in the long, black coat in a photograph (fig. 18) taken in New Haven in 1894 or 1895. If so, he would have been about fifty years old, which seems about right for this photograph. Wearing a white shirt with a crisp, stand-up collar, a satin bow tie, and a long, partially buttoned, slightly rumpled, double-breasted coat, he was photographed against a stark background, almost full-length, with one arm bent behind his back. He represents himself as upstanding, literally and figuratively, and self-sufficient, with no need to lean on anyone or anything. But the man in this photograph appears dour, not what one would expect from newspaper descriptions of James.

The last sitter whose identity is known is dressmaker Izetta Alexander (see fig. 10). Born in Rhode Island, she lived in New Haven and Waterbury until marrying and moving to Long Island around 1916.[76] In 1887, she was named secretary of the first African American branch in Connecticut of the interdenominational Young People’s Society of Christian Endeavor.[77] In 1900, she is listed in the US census for Waterbury as a servant living at St. Margaret’s School, where James was a chef, but at the same time, she was listed as a dressmaker, boarding in her parents’ home in New Haven.[78] As a single woman, she may have had to hold more than one job to support herself.

Also in 1900, Izetta was arrested for attacking her “sweetheart,” Johnson Haile, the handsome headwaiter at Scovill House in Waterbury, by the gate of St. Margaret’s School. The Bridgeport Sunday Herald, a white-owned newspaper, printed a sensational front-page story, framing the crime as

[t]he oft repeated tale of a woman of a certain class driven to the verge of insanity by jealousy and who for the time being is a maniac, thinking of nothing but her overwhelming love for a man who once professed to love her but who turned aside for another face and threw his promises and her heart to the winds. . . . Women of a certain class can hate even more fiercely than they have loved and the Alexander girl was one of these.[79]

This description of Izetta as a “woman of a certain class” may have been racially motivated and biased, and was certainly at odds with her demure photograph, taken in 1888 or 1889, when she was about twenty-seven years old. She wears her hair pulled back, except for a stylish fringe of bangs, and simple hooped earrings. She is tidily attired in a jacket worn over a high-button bodice, which she probably sewed herself, the bodice chastely fastened at her throat. She looks proper, serious, and wary, the opposite of the impulsive woman described in the newspaper.

According to the newspaper, Haile may have had it coming:

Johnson Haile has had years enough of experience with women and the world. He was a ladies’ man. He seemed to have solved the problem of capturing the affections of every woman he went after, colored or white, and he played fast and loose with them. He was popular. Everyone liked him, but many of his friends shook their heads and predicted that one day he would come to trouble. It was especially known that the Alexander woman was in love with him and that he had thrown her over.[80]

Another white-owned newspaper noted:

Every effort is being made to adjust the case without the interference of the city court. The accused’s friends are prominent in various churches. They are fully aware of the seriousness of the case, yet they say it was not done without serious provocation. Haile is well known as somewhat of a gay Lothorio and his own statement that he will withdraw the complaint providing the accused leaves the city is considered as evidence that he had grievously irritated her.[81]

Haile refused to prosecute, and the case was settled out of court for $100, about $3,700 today, possibly due to the intervention of Izetta’s friends.

Admittedly, Izetta had committed a terrible crime, but the long newspaper accounts expounding on Alexander’s and Haile’s characters lean a little too enthusiastically toward widespread, negative sentiments among white people that Black women were angry, argumentative, and emasculating and that Black men were hypersexual. These harmful stereotypes would gain even more traction in the media in the twentieth century.[82] Formal commercial portraits portraying African Americans as highly respectable, like the ones in the album, were a way Black people could intentionally present themselves to push back against these stereotypes.

Izetta could have had photographs taken after 1900 to help mend her reputation. A photograph projecting respectability was desirable because in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, cabinet cards circulated widely among family, friends, and suitors, and one’s photograph could have a direct impact on one’s fortunes. An illuminating source for the social use of photographs among African Americans is the diary kept by journalist and activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1862–1931). The diary dates to 1885–87, when Wells-Barnett was in her early twenties, living in Memphis, and not yet married. Earnestine Lovelle Jenkins notes in her study of nineteenth-century photographs in Memphis that Wells-Barnett mentions photographs, pictures, scrapbooks, and photograph albums in her diary at least forty-two times.[83] Wells-Barnett commissioned and traded photographs frequently to promote her active social life. Given the number of photographs of African Americans from across the country that survive from this period, Wells-Barnett’s love and use of photography was probably typical of other middle- and working-class Black Americans (figs. 19, 20, 21, 22). In her diary, she describes how trading photographs worked. Jenkins writes:

In general Wells exchanged photographic cards with suitors who first offered a photograph and then asked for one of hers. In 1885, a young man referred to as E. W. M. brought her “a fine cabinet photograph” when he called upon her one evening in April. She in turn “gave him one of mine.” In some instances photographs were used to renew an acquaintance. Around the same time, Wells wrote to a Mr. Avant asking him for a picture to renew their friendship, which he agreed and promised to do.[84]

In her early twenties, Wells-Barnett often wrote to the men who were her escorts and companions. Jenkins observes:

Whenever a letter she received was accompanied by a photograph, she took the time to study it. For example, she found a letter from Mr. Morris most interesting but upon first receipt of his photograph was surprised to learn how young he was. . . . While she honored his request for a picture of herself, she asked for its return because it was borrowed. She did, however, promise to “send him a picture of his own when she had her cabinets taken.”[85]

On one occasion, a friend of Wells-Barnett gave a photograph of her to an interested suitor without her permission. He showed it to his friends, and when Wells-Barnett found out, she was very offended. She was also annoyed when she requested back two photographs from a man she was no longer interested in, and he returned only one.[86]

It is easy to imagine the young men and women portrayed in this album’s “cabinets” engaging in the same practices. The uncertain path to a perfect match and the pains people took to maintain friendships and cultivate relationships, often by mail, helps explain why people dressed and staged their photographs with such care as well as why they ordered cabinet cards by the dozen. One can also understand why a young man in possession of a photograph like the one of a woman in a velvet gown (fig. 23) might be reluctant to return it upon request, or why a young woman might be annoyed if a photograph she requested back was not returned. For single male and female sitters, how to stand out and appear attractive to their peers while still conforming to fashion and norms of respectability was challenging but necessary.

African Americans in the Post-Reconstruction Era

While the experiences of each African American person, family, and community are unique, for African Americans overall the years after the end of Reconstruction in 1877 and into the early 1900s were a difficult and tumultuous time.[87] The United States was transitioning from an overwhelmingly agrarian society, which had been highly dependent on slavery, to one that was increasingly industrial and urban, which by law enshrined some rights but not equality. Many in the South were trapped in sharecropping arrangements that impoverished them, while prejudice and racism everywhere limited opportunities for African Americans to advance. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments granted African Americans freedom, citizenship, equal protection under the law, and the right to vote, but most political gains African Americans made during the era of Reconstruction (1865–77) were rolled back swiftly. White people who refused to relinquish or share power launched campaigns to intimidate Black Americans that robbed them of their rights and sometimes their lives. Jim Crow laws throughout the South mandated segregation in nearly every area of public and private life. While by the 1890s African Americans as a group lived better lives than enslaved people had by many measures, in terms of health, income, and literacy and mortality rates, they were still far behind average white Americans.

Despite these obstacles, African Americans persevered, fighting for better lives for themselves and their children. With the collapse of gains made under Reconstruction and the failure of traditional institutions and organizations to support them, African Americans provided their own networks of support, as they had always done, to improve living conditions, education, and opportunities for themselves.[88] Glenda Elizabeth Gilmore reminds us that “[t]he period from 1890–1920 is often called the ‘nadir’ of African American history, yet African Americans kept hope alive.”[89]

By 1890, some Black people from the South had migrated to the North and West, but more than 80 percent of African Americans remained in states that were formerly slave-holding states.[90] In the Northeast, New York had the largest population. By 1900, Connecticut’s state’s population was 908,420, but only 15,226 were African American, 1.7 percent.[91] New Haven was the city with the most African Americans, 2,887 people, 2.7 percent of the population.[92] The number and percentage of African Americans in Waterbury was smaller, only 540 people in 1900, 1.2 percent of the population, and 775 in 1910, only 1.1 percent of the population.[93]

Across the United States, a third of African American men and half of African American women were in domestic or personal service.[94] More than half of employed African American men worked as farmers or in other fields of agriculture. In the Northeast, where the photographs were taken, the employment story was different for Black and white Americans, mainly because agriculture was a much smaller part of the economy.[95] As in other Connecticut cities, one industry dominated in New Haven, hardware, and in Waterbury, brass production. Consequently, African Americans in Connecticut rarely worked on farms, but due to discrimination, neither did most work in the coveted skilled-manufacturing jobs Connecticut’s cities offered.[96] Overwhelmingly African Americans in Connecticut around the turn of the century were laborers or in domestic service.[97] Ida Allston Brown’s husband, Richard, who was a machinist in a large New Haven company, was exceptional.

There was a mix of skilled and unskilled occupations in Connecticut with a high percentage of African Americans, including draymen, teamsters, and expressmen; janitors and sextons; and waiters.[98] James Allston worked as a chef and janitor, one a skilled and the other an unskilled working-class job, yet it appears he earned enough to support a middle-class lifestyle for his family. Foster Robinson worked as an expressman, owning his own business and his own home, where his wife worked full-time keeping house for their large family. Compared to unskilled trades, skilled trades offered greater economic stability, better pay, and the potential for advancement. It is difficult to know where clergy fit in the Connecticut job classifications. Rev. Bell had also been an entrepreneur, and he had a good education; in their photographs he and Susan Bell present themselves as quite refined. Their well-being, however, depended on the economic health of the community where they were assigned, which supported the church and provided the parsonage. In Waterbury and other cities in Connecticut, nearly all African American men around the turn of the twentieth century were employed, and, as a group, the African American population was making its way forward.

For many, a better education was a path to a better life. By 1895, 1.43 million African Americans in former slave states were enrolled in school, close to triple the number in 1876.[99] Literacy rates overall skyrocketed, from about 5–10 percent under slavery to over 50 percent by 1910.[100] In 1868, Connecticut prohibited discrimination in schools based on race and made public education free, but Waterbury had already allowed all children between four and sixteen years of age to attend school.[101] According to the US census of 1900, close to 100 percent of African American school-aged children in Waterbury attended schools, and nearly all African American adults in Waterbury, including all those identified in the album, could read and write, which increased opportunities for employment. Literacy rates in other Connecticut cities were probably similar.

Rarely were African Americans in Connecticut subject to the violence they experienced in many other places. They were tolerated, if not welcomed, by the majority of the state’s populace. W. E. B. Du Bois writes that white people often thought African Americans living in New England and the Middle Atlantic states had “not formed to any extent a ‘problem’ in the North, that during a century of freedom they have had an assured social status and the same chance for rise and development as the native white American, or at least as the foreign immigrant.” But “this,” Du Bois says unequivocally, “is not true.”[102] Yet based on existing documentation, and despite obstacles and ups and downs, the people in the album and their families appear to have been more secure financially than most African Americans of their era, including others in Connecticut.[103] Making up such a small minority of the population was a big change for most of the African Americans in the state, who were recent migrants from the South.[104] Several of the people associated with the album, however, were born in the Northeast or had left the South before the Civil War. Because they were better established, they may have been better adapted for success in the Northeast than more recent migrants.

The African Americans in the album represent themselves as middle class, as people who had found a measure of success despite the odds. Even if middle-class status for some of them was aspirational rather than actual, their images project hope, confidence, and pride in what they had achieved. And a fine collection of turn-of-the-twentieth-century portraits in an African American family album also stood for something else: the privilege of collecting photographs of an intergenerational family, one that ancestors who had been enslaved were denied.[105]

Early Photography and African Americans

The role and significance of photography for nineteenth- and early twentieth-century African Americans cannot be overstated. Shortly after photography was invented in 1839, enterprising Americans, including African Americans, opened daguerreotype galleries and parlors around the country.[106] Americans enthusiastically embraced this revolutionary new picture-making technology, and Black Americans appeared in such photographs from the start.[107]

Daguerreotypes, however, were expensive, and very few African Americans could afford them.[108] Around 1850, when they were most popular, the largest, a full- or whole-plate daguerreotype, could cost thirty-three dollars—in today’s dollars, $1,300. Even the smallest examples cost between about fifty cents and $2.50, a stretch even for skilled laborers, who in 1860 earned an average of $1.62 per day. Daguerreotypes were out of reach for typical farm laborers, who at that time averaged $13.93 a month, never mind for unskilled labor or the enslaved.[109] Consequently, most daguerreotypes of African Americans were commissioned by their owners to document the owners’ “property,” with African Americans often literally pictured in supporting roles (fig. 24).[110]

Despite the expense, some African Americans commissioned daguerreotype portraits of themselves (fig. 25). The most famous of these is Douglass, the best-known African American and most widely photographed American of the nineteenth century.[111] Douglass used photography to shape his public persona and confront stereotypes about African Americans with dignified and powerful portraits that, along with his oration, “sent a message to the world that he had as much claim to citizenship, with the rights of equality before the law, as his white peers” (fig. 26).[112] The earliest photograph of Douglass, a daguerreotype from 1841, shows him as a young man, about three years after his escape from slavery, around the time he started his crusade as an abolitionist speaker.[113] This was one of 160 photographs of Douglass taken over a period of fifty years.[114]

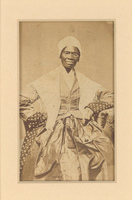

By the end of the 1850s, much cheaper alternatives to daguerreotypes had emerged, including ambrotypes and sturdy tintypes, which were often encased like daguerreotypes, and cartes de visite.[115] Produced at the same small size the world over, cartes de visite found homes in the first mass-produced photograph albums by 1860.[116] Inserted among cards from family and friends were those of famous people such as Abraham Lincoln (1809–65), Douglass, Harriet Tubman (1822–1913) (fig. 27), and Sojourner Truth (ca. 1797–1883), the last of whom used cartes de visite to take charge of her own image as a free woman (fig. 28).[117]

Cabinet cards, invented in 1866, were enormously popular by the 1880s; they are the dominant type of photograph found in the NMAAHC’s family photograph album. These photographs were larger than carte-de-visite photographs and were mounted on more substantial cards. They could be easily propped up on a shelf and did not bend and crease when sent through the mail. As Jenkins notes, “the edges of the cabinet cards were framed or enhanced to make portraits more elegant. Flattering positions and more ornamental backdrops and props helped the sitter appear more cultivated” (figs. 29, 30).[118] In addition, the extra length at the bottom of the card allowed the photographer to record the studio name and location on the front, underneath the photograph, and some studios also added advertising on the back of the card.[119] Photographers were listed consistently in city directories; they frequently relocated and went into and out of business, so cards with studio names and street addresses are often easier to date than those without.

By the 1880s, photographers had created landscapes, still-life compositions, scenes of everyday life, and even historical tableaux.[120] But for at least another decade or two, formal portrait photographs, taken in a commercial studio, were by far the most popular photography genre among all Americans, including African Americans.[121] The cost for a set of a dozen cabinet cards ranged from two to six dollars, an affordable luxury even for working-class people.[122] In turn-of-the-twentieth-century studios, the poses, lighting, and backdrops varied, but not by much. Even small cities like Waterbury and New Haven had several photography studios. Although all the studios in Waterbury and New Haven that are represented in the album had white owners, at least one studio in New Haven, the name of which is unknown, employed an African American: Richard Brown, Ida Allston’s son.[123] Black employees might have helped attract, photograph, and keep Black clients, but in any event, the African American sitters in the album went to white-owned studios and obtained dignified, attractive portraits. Where competition existed, studios produced acceptable likenesses, or their clients would take their business elsewhere.

Very few photograph albums, including albums of African Americans, have been researched and published, and even fewer are late nineteenth- or early twentieth-century family albums.[124] Most museums and archives do not collect photograph albums of unidentified people, especially African Americans.[125] Intact albums rarely appear on the market. The historical and regional coherence of photographs in the NMAAHC album, a fact supported by research, strongly suggests that they belong together, but as Henish Heinz notes, old photography albums “offered for sale have usually been raided for valuable contents, then ‘reconstituted’ by inserting photographs from a random pile, without historical cohesion, just to fill in the vacant spaces.”[126] Perhaps the most important reason few photography albums owned by Black families are collected and published is that they are retained and treasured by those families.

More recently, scholars and curators have paid more attention to ordinary, often commercial, photographs compiled in albums, believing, as Trent does, that “album-based archives are born in the gaps between dominant narratives,” countering “institutionalized acts of neglect, marginalization, misrepresentation, or erasure.”[127] Portrait photography of famous, little-known, and even unknown people calls for investigation into the role and potency of photographic representation. Often the emphasis of this work is on how photographs reinforce power relationships, but Trent is convincing when she argues that scholars “have overemphasized the dominance of European and North American, middle-class, white, heterosexual, feminized, ableist identity and visual power in operations of photography albums and scrapbooks.”[128] Studying how everyday people used photography can be particularly revealing when the subjects of the photographs were marginalized in their own time or have rarely been the subject of historical research.[129]

Frederick Douglass and Photography

“This may be termed an age of pictures.”[130] So proclaimed Douglass in 1862 in one of four speeches about photography he gave between 1861 and 1864–65, expounding on the topic more than any of his American peers.[131] These speeches are valuable for understanding the power and meaning of early photography for Black Americans. Douglass celebrates the verisimilitude and accessibility of photography:

A very pleasing feature of our pictorial relations is the very easy terms upon which all may enjoy them. The servant girl can now see a likeness of herself such as noble ladies, and even royalty itself, could not purchase a hundred years ago. Formerly the luxury of a likeness was the exclusive privilege of the rich and great; but now, like education and a thousand other blessings brought to us by the advancing march of light and civilization, such pictures are brought within easy reach of the humblest members of society.[132]

While the extraordinary ability to create a strikingly real portrait and the democratic nature of photography were two of the reasons that Douglass loved photography, these were not the only ones. He also posits photography’s potential to prove to white people the humanity of Black people and to help end slavery.[133]

This was a tall order. To understand how Douglass thought this was possible, it is useful to understand the type of photographs that he discusses. He is referring to photographs like those he had had taken of himself: formal, stylized portraits commissioned by the sitter, in which the sitter presents himself at what he considers his very best (see fig. 26). This form of picture making was objective but also deliberate. Henry Louis Gates Jr. notes that Douglass “presented a range of selves over time,” but every image is dignified and imposing, which shaped and still shapes his public persona.[134] For Douglass, a truthful photograph communicated to his peers and to those who would come later not only his appearance but also his character, which he hopes will inspire them. “It is evident,” he writes, “that the great cheapness and universality of pictures must exert a powerful, though silent, influence upon the ideas and sentiments of present and future generations. . . . They bring to mind all that is amiable and good in the departed, and strengthen the same qualities [in the living].”[135]

While Douglass demonstrates with his own image that portrait photographs could project character, he also argues that photographs could prompt viewers to see beyond what was represented. He understands photography in the context of “picture making,” a category that includes the creations of not only photographers and artists but also “poets, prophets, and reformers” who create “pictures of the mind as well as of matter.”[136] Their capacity to use “pictures of the mind”—imagination—to create a poem, a prediction, or a reform, he argues, “is the secret of their power and of their achievements. They see what ought to be by reflection of what is, and endeavor to remove the contradiction.”[137] Portrait photographs of Black people could be positive, objective, and truthful—as Douglass certainly considers his and other African American portraits to be—but they also forced viewers to reflect on the discrepancy between the humanity of Black people, proven by photography, and the many dehumanizing ways Black people were treated in real life. Douglass sees photography as part of a larger project: the envisioning of a better world and activating that vision by abolishing slavery and establishing a more just and harmonious society. “It is the picture of life contrasted with the fact of life, the ideal contrasted with the real, which makes criticism possible. Where there is no criticism, there is no progress.”[138]

From the 1860s forward, most African Americans knew about Douglass and his fight for freedom and equality, but few were familiar with his extraordinary lectures on photography.[139] It did not matter. African Americans knew from experience about dehumanizing treatment, and they understood intuitively the humanizing power of photographs before Douglass uttered a word about them, using progressively less expensive photographic technology to present themselves at their very best. As Willis and Barbara Krauthamer note, “Slaveholders’ and scientists’ images of enslaved women and men stand in stark contrast to the ways in which Black people represented themselves in the 1850s. Portraits commissioned by free black men and women, as well as images created by sympathetic white abolitionists, convey self-worth, dignity, beauty, intellectual achievement, and leadership.”[140] But while Douglass hoped these photographs would sway racist mindsets and inspire reform, the vast majority of African Americans in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries commissioned photographs of themselves for their own pleasure and to push back in the face of derogatory treatment, messages, and images.

The number of negative images of African Americans in circulation by the turn of the twentieth century was massive. Such images proliferated in newspapers, journals, and advertisements as well as on trade cards as wood- and copper-engraved illustrations through the time of the Civil War; they multiplied in lithography and chromolithography after the war, into the twentieth century and beyond.[141] However, even when photography became less expensive, racist images continued to appear mainly in printed form, probably because it was more work to stage or manipulate a photograph than to create a caricature from scratch.[142] When photographs did have a racist intent, on stereograph cards or photo postcards, for example, they often required a caption or obvious manipulation to hammer home their disparaging message.

African Americans, on the other hand, had multiple reasons for representing themselves with photographs. As Willis argues,

[B]lack photographers and their subjects believed that defining their own identity and beauty through photography was a significant step in the fight against negative representations. Photography played a role in shaping people’s ideas about identity and sense of self; it informed African American social consciousness and motivated Black people by offering an “other” view of the Black subject.[143]

Choosing to have one’s portrait taken demonstrated agency and allowed one to be seen as one wanted to be seen. Passing photographs among family and friends helped to build pride and solidarity, not only in oneself but also in one’s family, community, and race.

Studio Photography, Fashion, and Race

Photography historians never tire of commenting on the sameness of nineteenth-century and early twentieth-century commercial photographs, yet people loved them, and it was easy to recognize a face of someone you knew on a cabinet card.[144] But the people one knew in these photographs rarely looked as one usually saw them, when they were at home or dressed for work, school, or play. Instead, sitters wore their very best clothes for the camera, dressing as fashionably as their purses allowed. Like today, most people at the turn of the twentieth century did not want to look as they normally looked; they wanted to look better.

The adults in the album could have learned how to dress to impress from various sources. One was instruction from family and friends; another was to observe what others were wearing in real life and in photographs; and yet another was through the press, in fashion magazines and newspaper columns. Examples of fashion columns in African American newspapers include Fashion Notes in the Washington Bee,[145] the Woman of Fashion in the Cleveland Gazette,[146] and the sometimes-cheeky Fashions and Fancies column, which appeared in several papers:

Fashion now dictates that flowers shall be worn at the belt. This is an awkward place for them, as the arm is liable to crush them unless they are kept constantly in mind, and, as it is generally understood that to appear well dressed one must think a [great] deal about one’s clothes beforehand and nothing about them after they are on, this demand on one’s attention is rather a bore.[147]

The writers of these columns provide fashion advice specifically aimed at Black audiences who hoped to project images of themselves as fashionable and tasteful. The following passage also reveals a bias against African Americans with darker skin, part of a long and persistent history of colorism within Black and other communities that can impact the way someone’s character or worth are judged:[148]

Heliotrope [pinkish purple] in its various shades will again be the favorite color for spring wear, and let me warn dark-skinned people from donning this color, as it will only tend to darken the complexion, giving it a leaden hue and producing a disagreeable effect. Heliotrope, like corn or yellow gold, can only be worn by people of fair skins, as it always lends color to the complexion and does not take from.[149]

Heliotrope, first used as a color name in English in 1882, and other strong colors were all the rage in the 1890s and were very tempting, but they were not recommended for people with certain complexions because they were not flattering:

There are some very beautiful and brilliant shades of reddish pink now newly in vogue which are simply destructive to half the women who wear them. They are so brilliant that they kill all the bloom of a delicate skin and make it look either sallow or lead-colored. The deep vivid blues and royal purples now worn are almost as bad—fully as bad, indeed—for dark complexions. For general becomingness nothing can equal the combination of black and white; so if a woman is determined to venture on a brilliant and dangerous color she will do well to make it only an adjunct to a black and white costume.[150]

Men did not get off easily, either:

The neck gear that the men beautify themselves with make some of them look like tiger lilies and poppies. Gentleman should be as careful in the selection of their garments as women. A badly dressed man is as unpleasing as a badly dressed woman, and an overdressed man is unpardonable. We can manage to look with pity upon the vanity and mistakes of a woman in this matter, but in a man it is disgusting and chokes up the vein of pity.[151]

Nearly all fashion magazines were geared toward mainstream readers, that is to say, white middle- and working-class women, but in 1891, Julia Ringwood Balch Coston of Cleveland, Ohio, began publishing Ringwood’s Illustrated Journal of Fashion, Needlework, Reading, the “first published [women’s magazine] to represent colored ladies,” for a subscription price of $1.50 a year.[152] One African American newspaper described it as “handsomely printed in book-form with artistic fashion plates of colored American women and important hints on the latest fashions.”[153] Ringwood’s encouraged Black women to consider the image they projected, undoubtedly reinforcing messages they had picked up elsewhere.[154] The advice it offered “communicated to the readers that the idea of personal style is a public display of morality that could combat negative stereotypes of African American women.”[155] Geared to two audiences, the magazine addressed “the elite class of Black women, for whom fashion represented class position, and working-class women, for whom appropriate fashion choices indicated moral respectability despite their occupation” in domestic service.[156] Mary Church Terrell wrote for Ringwood’s. Jenkins notes that in the issue of the magazine for May–June 1893, Terrell addressed

the relationships between race, class, morals, and fashion. Her understanding of the role that elite African American women should play in setting an example for black women in lower social circumstances was in keeping with the philosophy of racial uplift that dominated the journal. Terrell wrote that the manner in which African American women dressed in public was not only a reflection upon the self but also one’s family, friends, and the entire race.[157]

Although Ringwood’s, later known as Ringwood’s Home Magazine, ceased publication in 1895, the messages it conveyed, especially pertaining to racial or social uplift, persisted in later publications directed toward Black women and toward African American audiences in general. This includes The Crisis, the official publication of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), founded in 1910 by Du Bois, who edited the early volumes of the magazine, which included a list of notable examples of “social uplift” in its first issue.[158]

Advice about fashion and presentation encompassed posing for a photographer. Florence Williams’s words in her essay “How to Take a Good Photograph” for New York Age is worth quoting at length:

I often stop and look at the photographs displayed in cases on the sidewalks and in the windows, and I must give actors and actresses credit for knowing how to dress and pose in this particular. Their gowns and costumes are always plain, and I should judge in regard to the materials that cottons, wool and velvet had the preference. Silk and satin are two materials that most people think they must wear when having a picture taken. It is a mistake and any photographer will tell you that the shiny, glimmering effects are bad. Now if you want to wear a dress to produce a light color, use white, grey, pearl, blue or green. These colors take white. Tan, yellow, and dark brown take black. Don’t wear white gloves unless you have a small hand. If you must wear any at all wear dark colors. They produce a better effect. If you have a large foot don’t stick it out, no matter how pretty the shoes may be because, if you do, when you see it in the picture, you will wish you hadn’t. Let the hair be plainly arranged and not elaborately, for remember the style changes every year, and it will look funny in a few years and not at all like you. Use as little cosmetics as possible for the complexion. The artist looks after that part when finishing up the picture. Don’t laugh unless you can do it prettily and naturally. A meaningless grin is dreadful and will spoil the prettiest face in creation. Better not attempt it unless you can do it well. . . . I advise women never to have their pictures taken in her hats or bonnets. The fashion of to-day is gone in six months and I am quite sure that the plates of bonnets are preserved with the year, or the date of the style when worn. It might be embarrassing in years to come to compare the lady’s portrait with fashion plates used fifteen and twenty years ago. Don’t try to strike a dramatic attitude but always try to be natural.[159]

Nothing Williams says makes it obvious that she was writing for African Americans, but her Black audience may have caught coded references. One is the admonition against smiling too broadly, which may have been intended to discourage Black sitters from being photographed in a way that might unwittingly evoke the grotesque “grin” of many racist Black caricatures.[160] Likewise, racist images often show African Americans in demeaning, melodramatic poses and portray them as ungainly and shambling, perhaps the reason the writer discourages dramatic “attitudes.” Even the advice to stick to plain “gowns and costumes,” forgo hats and gloves, and avoid fancy hairstyles—reasonable advice for anyone—may have resonated differently with Black audiences, given how frequently African Americans were presented in racist images as buffoons, donning mismatched, ill-fitting clothing and wearing outrageous hats or wild, unkempt hair. If this is so, the writer allows her Black readers to read between the lines, sparing them the indignity of explicit reminders of ugly stereotypes and emphasizing instead how to create a respectable, understated, and timeless image.

One of the difficulties of reading photographs from more than a century ago for signs of social and economic status is that it is impossible for us to see them with the nuance of turn-of-the-twentieth-century eyes. We can look for clues based on what we know about the clothing and fashions of the day, but clothing and fashions can be deceptive—just as many of the sitters intended. In the 1880s, the rise of department stores, mass-produced and mail-order clothing, home sewing machines, and an abundance of patterns for sewing clothing resulted in what Joan L. Severa calls “the democratization of fashion,” making it harder to classify people’s social class, income, or occupation simply based on what they wore.[161] While people at the time were probably more astute in noticing differences in quality in the formal dress worn by their contemporaries, everyone was wearing the same styles, “dispensed and consumed in a manner that helped create a national norm.”[162]

To the extent that they could, most people of all races in the United States adopted the markers and the lifestyle of the middle class, and they were determined to project that image in their photographs. People about whom nothing was known often appeared to be middle class in photographs based on a shared understanding of what middle class looked like. Severa argues “that there was a very powerful drive toward a ‘proper’ façade. It was of tremendous, almost moral significance during the nineteenth century that one appears cultured.”[163] For African Americans, the stakes were even higher because they needed their portrait photographs not only to project middle-class respectability but to avoid depictions of themselves that in any way played into damaging negative stereotypes. The wrong sort of photograph could make someone appear disreputable even within their own community.

Photography, Storytelling, and Racial Uplift

Perusing a photograph album can be a solitary experience, but people often enjoy albums together as well. Martha Langford describes the social interaction that occurs when two or more people browse a photograph album as “an oral-photographic performance,” where photographic culture and oral tradition meet to create meaning from the assembled photographs.[164] When people converse while looking through a photo album, “the album gives voice to the intensity of human experience” and the photographs come to life.[165] The photographs in an album likely make the stories told about the people represented in them more vivid, and those stories no doubt impact the perception and interpretation of the photographs by those sharing the album.

Memories are what make albums special.[166] Rarely, however, are memories of the people who compiled or enjoyed an album recorded. Instead, it is usually through stories, passed down through generations, that the memories are preserved. This can make collecting family albums for a museum or archive problematic. Langford writes, “Voices must be heard for memories to be preserved, for the album to fulfill its function. Ironically, the very act of preservation—the entrusting of an album to a public museum—suspends its sustaining conversation, stripping the album of its social function and meaning.”[167] The NMAAHC photograph album is an orphan, separated from its family before the donors acquired it and gave it to the museum. Research on orphan and other albums owned by museums and archives may, however, allow collecting institutions to identify and find people descended from those represented in the album and invite them to continue the conversation from their perspectives.[168] For the NMAAHC album, this process is underway. When families donate or sell photograph albums to museums and archives, these institutions have an obligation to collect information from the owners to preserve not only the physical album and its contents but also the stories associated with them.

What sets the NMAAHC album and others that belonged to Black American families apart from other photograph albums is their role in passing down Black family, community, and national history and their emphasis on racial uplift. This resonates with the more recent experience of Willis, an African American historian of photography and a photographer, who, when writing about albums, including those in her own family, states that “images of family life and events in the photography album are shaped and narrated through the voice of a family member or keeper of the album,” and compares the performance of photograph albums owned by Black families to a celebrated aspect of their African heritage, that of the griot.[169] She quotes Charles L. Blockson, who writes, “In Africa, each family has a griot or archivist who committed the entire family’s history to memory. Each griot, in preparation for death, would hand over his entire log of historical stories to a younger man, who became the new family historian.”[170]

The tradition of the family griot was one among many that slavery disrupted as it ruptured familial ties. Yet Black people who were enslaved had a compelling incentive to maintain and expand oral traditions: most were prohibited from learning to read and write, and storytelling was one of the only ways to pass along anything they thought was worth knowing. Storytelling remained important long after emancipation and the rise of Black literacy for the sharing of Black history and culture and as a powerful, popular, and widespread means of instruction, entertainment, and remembrance.[171]

The community represented in the album was literate, but at the time, most integrated schools and the mainstream press taught little about or devoted little coverage to Black history or Black contributions to American society. Storytelling helped to remedy this lack. Furthermore, except for entries in the family Bible, few families wrote down their family histories. Combining the ancient tradition of the griot with the modern technology of photography empowered African Americans, like those in the album, to tell and retain their family stories, expound on their progress, share their sorrows, and pass on lessons about how to survive to the next generation. Like the African griot, the album’s storyteller recited “not merely the chronicles of who did what when, but composite word-pictures of the culture, belief, ethics, and values of the tribe.”[172] But unlike most griots, the storyteller was usually female, and she was not compelled to recite the chronicle the same way each time.[173] Instead, she could adapt the story as she wished, depending on the audience and her intentions. It was her privilege to guide the narrative, but she did not necessarily control it.

bell hooks, a theorist, educator, and activist, also writes about the role of storytelling and photography, describing walls covered with photographs in Southern Black homes like the one she grew up in: “As children, we learned who our ancestors were by listening to endless narratives as we stood in front of these pictures.”[174] She comes to see such photographs as “a disruption of white control over Black images” and identifies them as “sites of resistance.”[175] She favors snapshots, which allowed family and friends to control how Black people were portrayed and countered negative images of them in the media. She confirms what earlier Black families intuitively understood: “the camera was the central instrument by which Blacks could disprove representations of us created by white folks.”[176]

hooks argues that the “public announcement” of photographs hung on walls was quite different from photographs in albums, because in her experience albums were put away and seen only upon request.[177] Fifty years earlier, however, photograph albums were displayed in the parlor of a home as part of the middle-class culture of that era. The worn condition of the NMAAHC album affirms that it was frequently shared. Those who compiled and perused this and other albums like it undoubtedly understood them as a challenge to white prejudice and a place to resist erasure. Writing about albums owned by Black families, Cheryl Finley notes that “albums possessed a different hold on memory” than individual photographs, because “family albums connected one generation to the next,” and “with each photograph, the storyteller guided the construction and reconstruction of identity, the formation of the social group in relation to a larger history of humankind.”[178]

Acceptance without Assimilation

Where African Americans fit, not only in the larger history of humankind but also in the present, was the subject of much debate outside and within African American communities in the post-Reconstruction era. Those pictured in the album chose to conform to contemporary norms of middle-class respectability, but this does not mean their goal was to assimilate into mainstream white society. As a practical matter, unlike most European immigrants, most African Americans, because of their complexions, could not expect to eventually blend into mainstream society in the United States simply by speaking English, publicly adopting “American” habits and customs, and dressing in a particular way.